Colin Read • June 10, 2022

A Bad News Quinfecta This Week - June 12, 2022

A Bad News Quinfecta This Week - June 12, 2022

All signs point to something none of us want to contemplate. The fundamentals suggest a recession, and perhaps a stagflation.

First, the inflation rate is just shy of 9%. The most recent report came in with an 8.6% inflation rate when many commentators and politicians were predicting or hoping for a moderation rather than an acceleration of inflation.

Comparisons to the stagflation of 1980 are inevitable. Then, as a response to energy supply shocks that accumulated over many years and arose from OPEC oil price increases, the buying power of the US dollar declined precipitously as the inflation rate rose to peak at 14.8%. The supply shock increases were reinforced by Cost of Living Allowance (COLA) clauses in union contracts that mandated a wage increase when prices rose. Of course, these wage increases resulted in increases in the price of production of goods and services, and hence further price increases.

The upward spiral in inflation this time around is a bit different. It was led by inadequacies in the supply chain, which, as four decades before, increased supply prices. But, unions are much less prevalent or powerful in 2022 and COLA clauses are rare. Rather than a self-reinforcing inflation, today’s acceleration is simply due to poor fiscal policy. At a time when the supply chain was struggling, a pair of presidents and Congresses chose to engage in a spending spree funded by an unprecedented level of deficit federal financing.

While this fiscal folly may have been politically popular, it was also economically equivocal. To pump trillions into the pockets of households and businesses, but without the supply of goods and services to purchase, prices inevitably had to rise. In addition, with little to buy, savings rose substantially, which kept interest rates down. The high savings rate and low interest rates ensured that these politically motivated fiscal gifts kept on giving, and shall for some time yet.

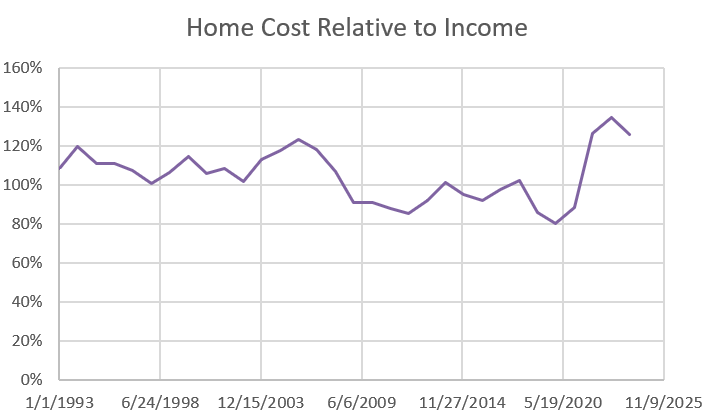

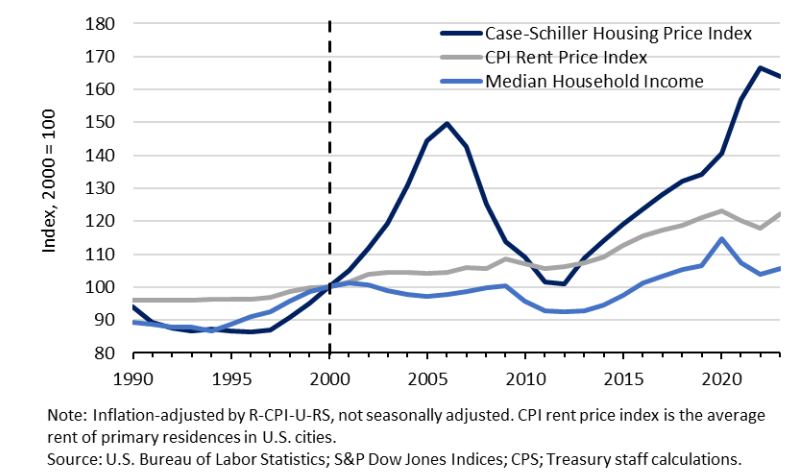

In essence, our leaders provided the kindling that turned a brushfire into a raging forest fire. Housing prices rose with all other prices, and the stock market experienced an asset bubble - until the inevitable.

Second, almost $4 Trillion of household wealth has been wiped out once the market appreciated the extent of the problem. Stock markets corrected, and crypto markets plummeted. The decrease in wealth, combined with depletion of savings as people started purchasing post-COVID, meant that latent demand has declined precipitously.

Third, this decrease in wealth and purchasing power is compounded by inflation to translate into an even further decrease in buying power. The sticker shock of higher prices causes people to reflect on whether and how they spend their dwindling savings. Wage increases have fallen way behind price increases, and the labor force remains contracted, which translates into a false sense of security arising from a low unemployment rate.

Fourth, inflation is now underestimated because of a quirk in the way we measure inflation. This is perhaps the great hidden story. The Great Stagflation of an inflation-induced recession in the late 1970s was long in coming. With the appearance of inflation during the Nixon Administration, President Nixon negotiated with Fed Chair Burns to avoid tight monetary policy if Nixon would impose wage and price controls. Such controls in a free market economy tend to be undermined through all kinds of mechanisms, and hence provided little long term remedy. As inflationary forces accelerated over the decade, almost Draconian monetary policy became necessary.

In the aftermath of an economic era many of you may well remember, it was proposed that the nation adopt another primary measure of inflation that omits the effect of high energy prices and on increases in agricultural costs that also arise from high energy costs. This “core” inflation that omits these two factors was designed to remove “transient” elements of inflation. Yet, if these transient elements are both important and longer lasting, such a removal causes the Fed and our leaders to underestimate the extent of the problem.

Indeed, if we measure inflation now as we did then, it turns out that the Draconian measures imposed during the 1979-81 recession are warranted again today. The levels of inflation, when measured consistently, are about as dire now as then, the brilliant Nobel Prize winning economist Larry Summers and colleagues Marijn A. Bolhuis and Judd N. L. Cramer recently recalculated inflation to make the measures consistent. The graph they generated (above) shows that today’s inflation rivals the post-WWII inflation and is rapidly rising toward the historic 1979-81 inflation. Given that wages are lagging significantly behind inflation, savings are depleted, and the labor force has declined in size, the significant decline in purchasing power may well result in at least two quarters of negative real economic growth. For only the second time in our modern economic history, we may well be experiencing a stagflation when inflation occurs during a recession.

Fifth, it is now widely accepted that the Fed responded much too late to the current inflation, and must now ratchet up their tight monetary policy more rapidly than their typical gradualism would prefer. For politicized reasons, the Fed seemed reluctant to squarely address inflation a year ago as President Biden was contemplating new members for the Fed and a nomination for the Fed chair. Such a politically charged era is not ideal for proactive monetary policy.

Some incumbent members of the Fed expressed grave concern about inflation last year, but they did not speak for the Fed. Fortunately, one member, Lael Brainard, was made Vice Chair of the Fed, and has advocated for more dramatic increases in the interest rate to slow the economy down and eradicate inflation.

Nobody wants to be the person who pulls away the punch bowl, but sometimes adults must make difficult decisions when economic children refuse to do so. This time has come. The difference between a mile and a deep recession is early anticipation. Gradualism works if anticipation is sufficient. But when non-economists run the show, perhaps without theory behind them, nor the economic history of what has come before them, politics trumps economics, and we all eventually pay the price.

These five factors do not bode well. I might add a sixth factor, but I do not do so for fear of labeling this phenomenon a sexfecta. Certainly enough arrows are all pointing down, with each new wave of economic measures a bit worse than the previous ones. The one arrow of a low unemployment rate is just enough for politicians and pundits to maintain some artificial hope as they probe too little into the Great Retirement and its artificial effect on the unemployment rate.

Indeed, President Biden invokes the low unemployment rate to argue that inflation is not a big threat to the economy. This again shows the gulf between politics and economics. The overheated job market and the desperation for firms to find workers who haven’t checked out is exactly the sixth factor that makes this perfect storm (times two) so dangerous. Wages ratcheted up in the Great Stagflation because of COLA clauses. Now they are ratcheting up because so many people retired from the workforce. Either way, the landscape is troublingly ideal for a wage-push inflation to take over where the cost-push inflation started off.

Oh, and the consumer sentiment index has reached its lowest level on record.

President Biden’s hope is a dangerous thing. When Pandora pulled sickness and death, war and pestilence out of Pandora’s Box, eventually the only civil malignancy left was hope. This artifact of deceptive expectations has replaced reason and economic rationality. The Fed seems to be coming to its senses, albeit slowly. The President is now all too willing to have the Fed take the responsibility, and hence the blame for what could be a rocky economic road ahead of us.

What a shame that much of this was avoidable.