Colin Read • March 5, 2022

A Bit of a Pickle - March 6, 2022

It looks like we are turning back the clock a lot these days, eighty years since the last slaughter of Ukraine civilians in the hands of an invading army, and forty years since robust inflation last struck the United States.

Hitler’s invasion of the Ukraine, which began in 1941, resulted in almost a million Ukrainians seeking refuge to the east. Now, more than a million have already sought refuge, this time to the west. Many millions died then, and perhaps many millions may again die as Ukraine is a pinball in east-west conflicts.

Given their pain, it is difficult to dwell on fear of a double digit inflation. But, it is also a learning moment with regard to our willingness to share the pain to stand for justice.

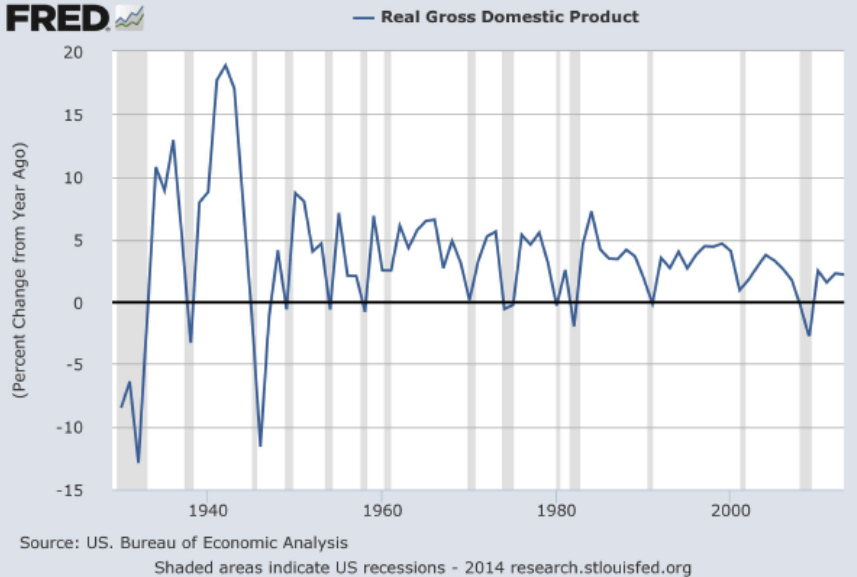

Yes, inflation is a problem, and is surely preoccupying Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. We can learn from history, if we choose.

Milton Friedman once correctly asserted that the problem in the 1979-82 stagflation was not because of a central bank printing too much money, but rather a central bank fighting an economic battle with one hand tied behind its back. While the Federal Reserve zigged, the Reagan Administration was zagging toward excessive fiscal spending.

In fact, these two important agencies of the people’s work were working cross purposes. I’m afraid that, if the measure of good policy is successful coordination, rarely do we see good policy.

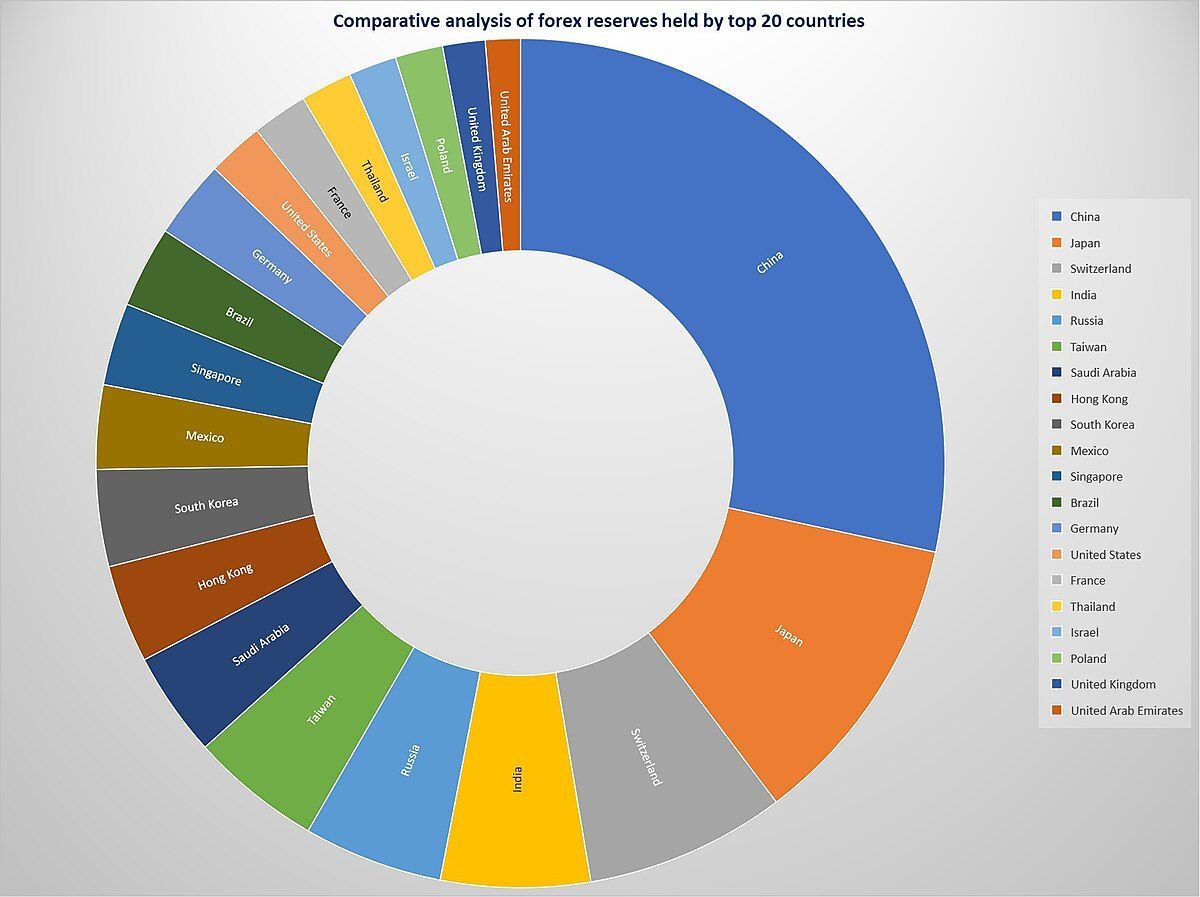

The root of the stagflation actually began years earlier. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries remained angry with the United States for its support of Israel in the Six Day War in 1967. This resulted in an oil embargo followed by dramatically rising prices. It was their oil, and I can’t begrudge OPEC from using the only instrument they had for purposes they felt were right, whether I agree with them over the issue at hand or not. I also believe we have the right to collectively sanction Russia for their atrocities today. Free markets mean that we are also free to use our supply and demand for purposes other than solely to make money. Sometimes standing up to our principles is expensive.

What got us into a bind in the 1970s is our unwillingness to pay the price OPEC demanded. If the OPEC nations insisted on a higher price for their oil, then we should acknowledge that it will inevitably take a bigger slice out of our economic pie.

Instead, we fought it. Rather than absorb this redistribution and accept the inevitable increase in energy prices, and hence inflation, for a couple of years, we tried to indemnify ourselves from it. We insisted that those higher prices be compensated through higher wages, which then required another round of price increases, this time not from higher energy costs but higher labor costs.

These higher prices then resulted in another round of wage demands, and so forth, until we were caught in a vicious cost/wage/price/wage/price spiral. Instead of taking our medicine, we ignored the disease and treated the symptoms.

By 1979, that left the Federal Reserve as the only adult in the room, and Congress to fight it. Well, after a couple of years of severe pain, double digit inflation, unemployment, and interest rates, the economy finally cried uncle and accepted the medicine much more severe than was initially necessary.

We find ourselves in that bind again. Will we accept higher costs, partly because of COVID complexities, and now partly because sanctions often hurt those who sanction as much as the sanctioned? Or, will we instead insist on redressing economic imbalances by increasing wages, or perhaps paper over international tragedies?

Invariably, when we pretend things aren’t as bad as they are, and we are unwilling to do the right thing, we end up paying a price much dearer. The prelude to World War II, the use of power to preserve an unjust status quo, attempts to indemnify us from structural changes that raise prices, or, now, the fear of punishing those who commit war crimes so we may keep gas prices down all haunt us eventually.

Powell recognizes, perhaps a bit late, that high costs and energy prices must be accommodated and accepted. If it means that we must face some economic hardship, in the form of higher interest rates and lower economic growth, then so be it.

We must accept both higher inflation in the short term, and higher interest rates in the longer term as a price to pay.

Economists define a “misery index” as the sum of the inflation and unemployment rates. Similarly, we could look at the sum of the inflation and interest rate. Both are unpleasant, but sometimes both are inevitable and must be accepted. What concerns Powell is acceptance of an inflation mindset that tries to neutralize it with higher wages rather than a bit of pain. It is the avoidance of some temporary discomfort that gives rise to inflationary spirals and many social quandaries.

The problem is that elected officials are often most concerned about getting reelected, or have their party not suffer too much in midterm elections. They perceive that voters vote with their pocketbook, and perhaps they are correct. Bill Clinton took James Carville’s advice that “it’s the economy, stupid.” Instead of working to build a much stronger economy for us all in a few years, politicians often advocate for the expeditious solution this year. Seemingly always, such short term political opportunism results in long term economic dysfunction. But, at least they believe they will get reelected.

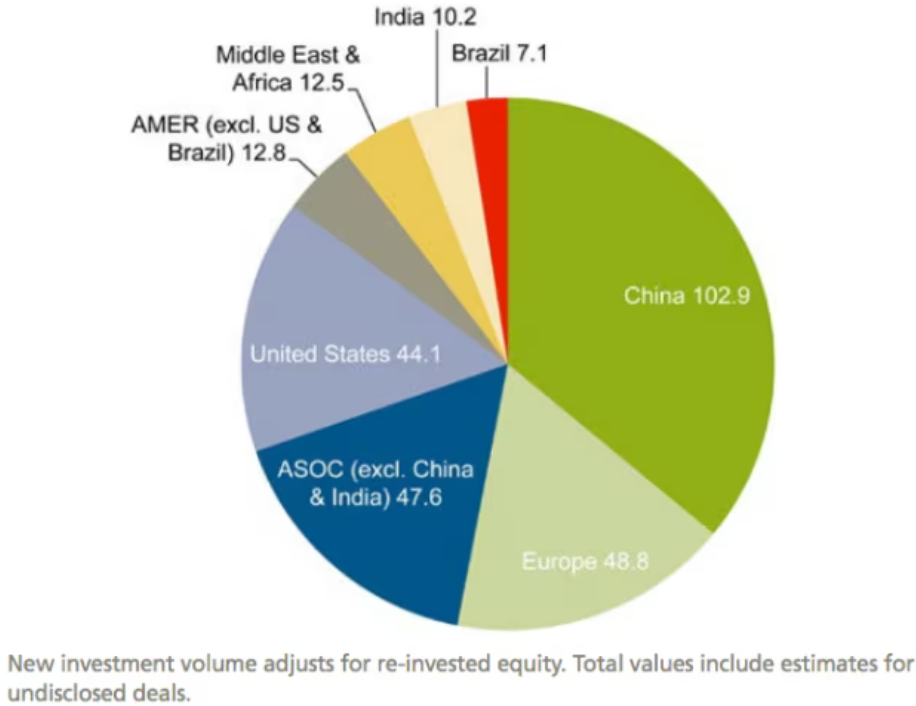

I’m reassured, though, that a recent poll showed the vast majority of Americans would accept higher prices at the pump, and presumably higher prices elsewhere as energy costs propagate across the economy, to do the right thing and ban imports of 8% of our oil that comes from Russia. Of course, Russia will instead just sell that oil to China. Sometimes, to show strength and do the right thing, it is costly, ineffective, and inconvenient.

However, if we don’t stand up for principles, we can’t stand for much. In this case, the defense of a defenseless Ukraine seems like a most compelling case to send the right message, even when it hurts our own economy. It was probably equally pragmatic for Chamberlain to appease Hitler, or for the U.S. to involve ourselves in other nations’ wars in the 1930s. But nor did that pragmatism work out so well.