Colin Read • November 19, 2022

A Drop in the Bucket - November 20, 2022

As the 27th meeting of the Conference of Parties of the United Nations Climate Accord, we were reminded of an inconvenient truth. The developed world had a number of years ago pledged $100 billion to ameliorate damages inflicted upon developing nations as a consequence of global warming. Yet, these developed nations have actually funded less than a hundredth of what was promised. It seems like differences between need and actions follow this ratio consistently. We are only willing to fund a hundredth or a thousandth of what is necessary to deal most efficiently with the problems at hand.

The problem comes down to economic justice. Let’s say you are walking along and spot a sack of cash sitting by the side of the road. Under the premise that possession is 90% of the law, you pick it up and go on a spending spree. Then, the rightful owners come along. Rather than paying back the cash you enjoyed, you offer to share the little that is left with the true owners.

The law is clear, though. The cash is the property of someone else, so the finder is not entitled to spend it. So much for the possession is 90% of the law motto.

The world’s nations are facing that same predicament. While we may argue that our exclusive economic zone affords us the right to enjoy the resources within our political boundaries, we aren’t entitled to deprive others of their resources. The Gulf War was caused in part by Iraq’s cross drilling for oil into Kuwait’s reserves. International law is clear about resource exclusivity. Just as with found cash, ignorance is no defense of the law of resource access.

The atmosphere is a resource we all share. We often speak of polluting our shared atmospheric resource when we emit anthropogenic global warming gasses. However, pollution differs from these emissions in that the Earth is able to clear pollution within a reasonable time, and the effects of pollution are typically local or regional, even if a region may occasionally span a border.

Greenhouse gas emissions should instead be considered consumption of a fixed resource. In the 1980s humans realized that our emissions of chlorofluorocarbons was breaking down ozone in the tropics and the flow of air toward the poles resulted in growing ozone holes at extreme northern and southern latitudes. The Montreal Protocol was eventually signed by all United Nations members, and the wealthiest nations ceased CFC releases and created a fund to ensure developing nations could employ alternatives to CFCs so they may grow as had the developed nations.

That treaty was not too difficult to negotiate because the human costs of a depleted ozone was most problematic for arctic and temperate nations, in the form of higher rates of skin cancer and other health concerns. But, CFC emissions anywhere were emissions everywhere, so it was worthwhile for developed nations to ensure developing nations would not repeat the mistakes we made. The sums transferred to developing nations were large but the benefit/cost ratio was large enough to justify these transfers.

CFCs are global warming gasses that persist for sixty to eighty years. The ozone hole is slowly repairing itself in the wake of international cooperation and enlightenment. And, since the developed nations caused the problem, it was ethical for them to bear the burden of solving the problem.

CFCs are only minor global warming gasses, though. They represent only a percent or two of the problems with global warming today. While they persist for perhaps sixty to eighty years, this duration is short compared to the centuries-long effect of carbon dioxide emissions, or the very pronounced and potent effect of methane emissions for about seventy years before methane then degrades to carbon dioxide and water vapor.

In other words, these gasses do not pollute the atmosphere so much as they consume the atmosphere for centuries.

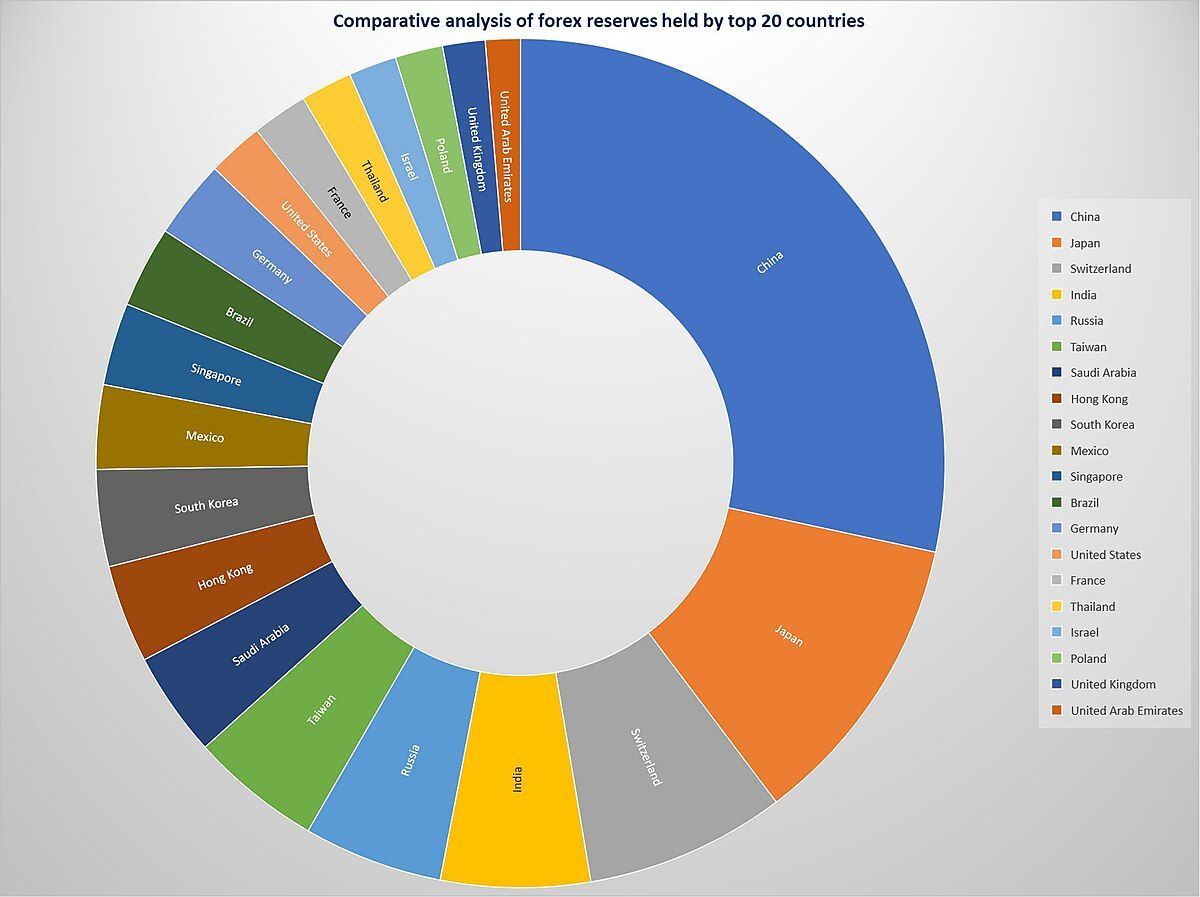

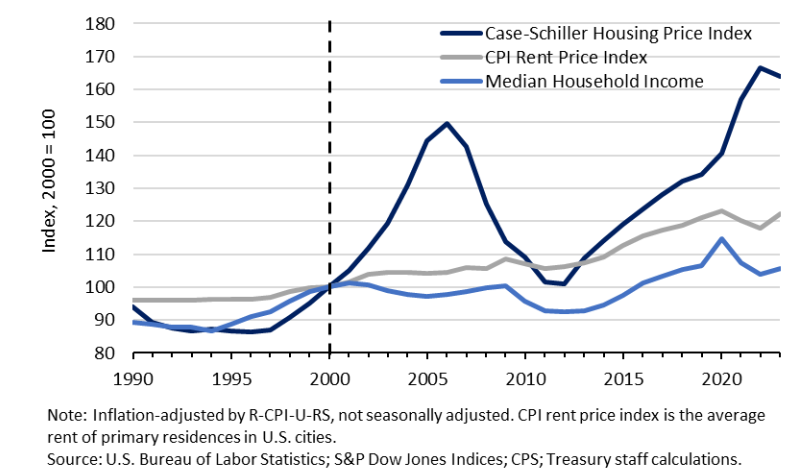

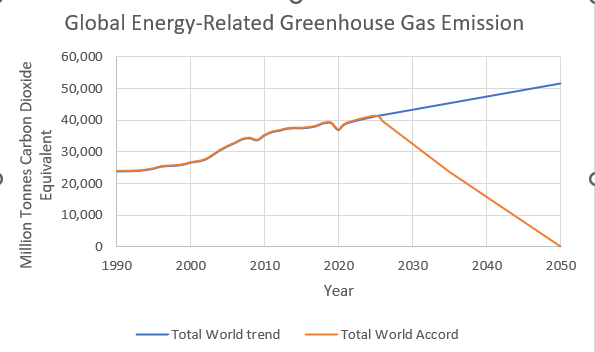

If the atmosphere is a resource that has been consumed, mostly by the United States in the past, but now by China and India as well, there remains far less ability for countries slow to use up the atmosphere for their own economic development. Continuing the analogy, The largest and most developed countries have spent much of a bag of cash that belongs to all countries and all generations, and are now of the opinion of my bad but let’s just move in by demanding all nations reduce carbon dioxide and methane emissions by 50% by 2035 and be net-carbon-zero by 2050.

In other words, a few nations spent 90% of the cash in the bag, but now offer to share the remaining 10% of the capacity for the atmosphere to absorb more emissions without triggering cataclysmic tipping points that cause runaway global warming.

This dilemma and convenient misapplication of the law is the subject of the 27th annual Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Climate Accord (COP27) in Sharm El-Sheikh. For the first time, there may be some acceptance of the responsibility of those who benefitted from spending 90% of the atmosphere’s capacity to further their development to now provide some funds to less developed nations to repair damage such as global warming-induced floods in Pakistan and to provide the developing world with access to funds to build a sustainable energy infrastructure so they don’t do to us what we have done to them.

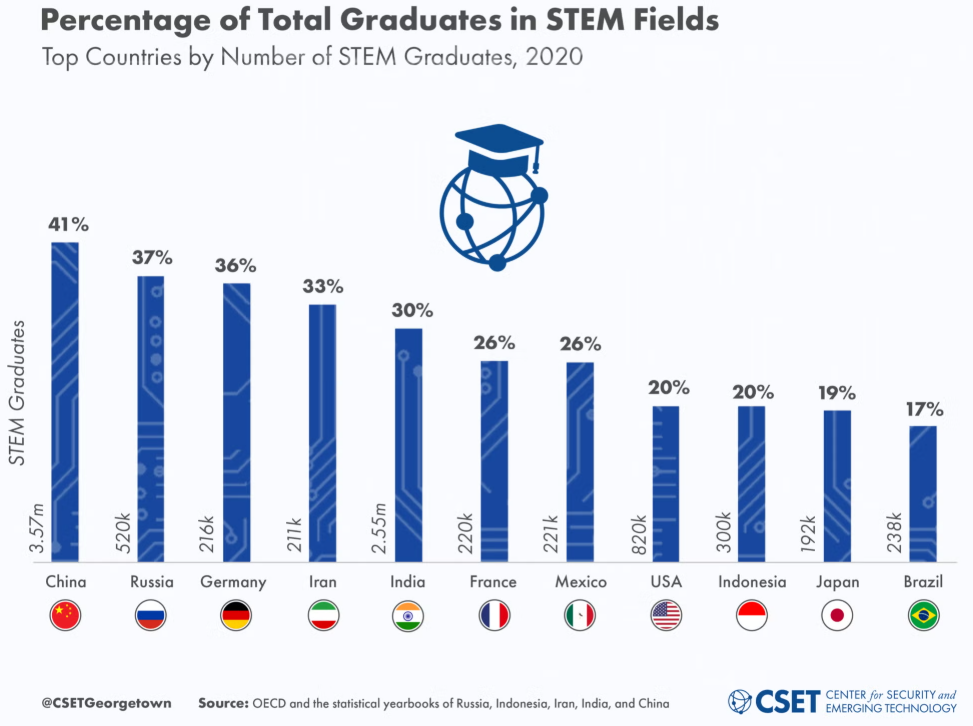

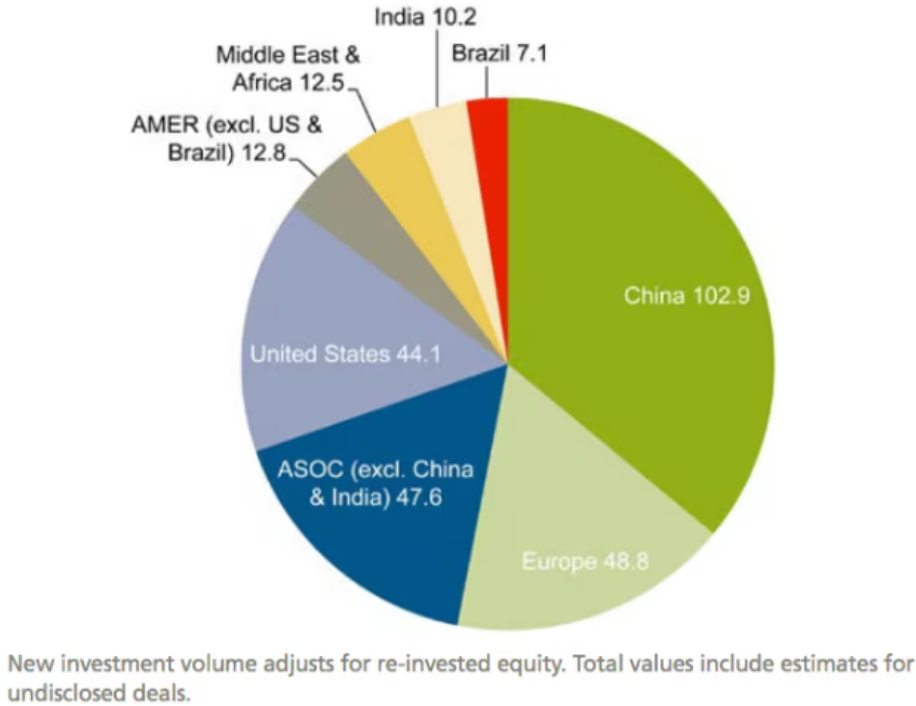

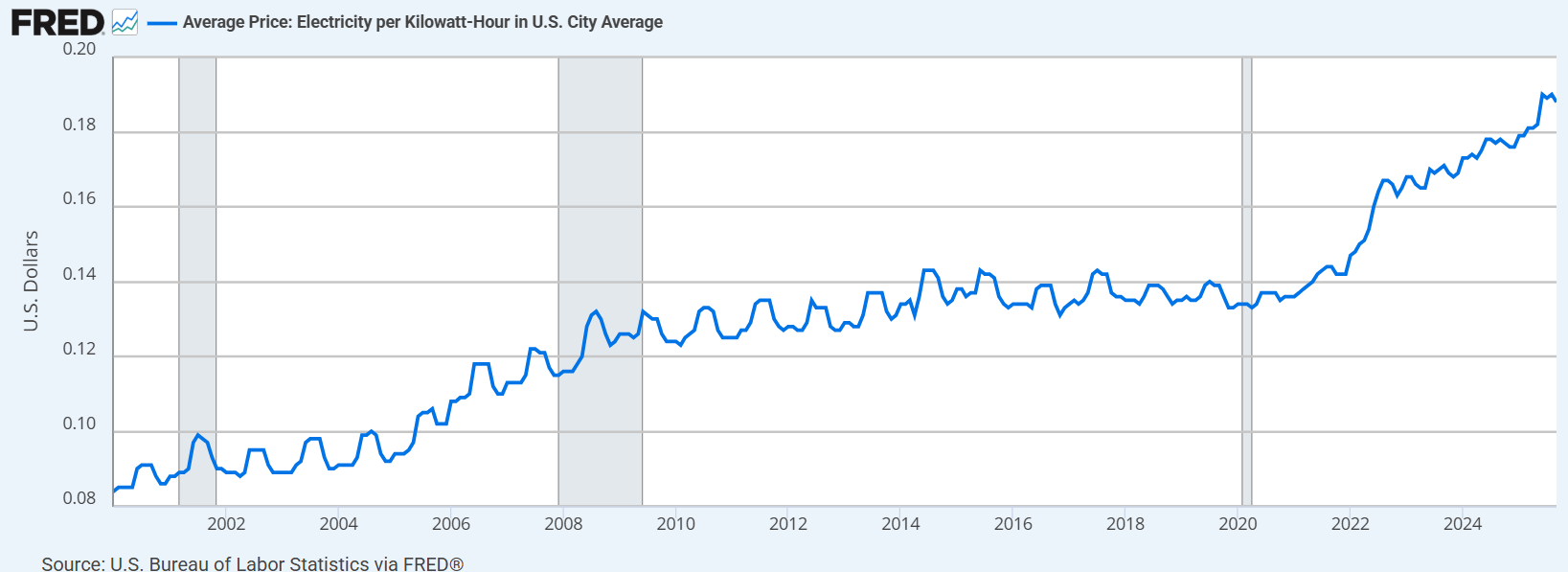

The problem is that the developed nations are offering a sum of millions or billions, while the loss and damage to less developed nations totals hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars. For instance, the costs of floods in Pakistan that destroyed homes for 10 million people and wiped out crops for one to two years will cost that one nation alone about $30 billion. The costs to move the planet to 100% sustainable energy totals in the tens of trillions of dollars. The developed world has access to private funds to make this transition, with China the largest producer of sustainable energy technology and production, but also electricity production from the burning of coal. There is no way that the developing countries will have access to the investments they need to ensure they don’t repeat our mistakes.

The developed and large countries don’t want to pony up to spending 90% of this fixed resource because the cost to do so is in the trillions of dollars, not the millions or billions. Nor do the temperate nations feel the large brunt of the displacements. The U.S. represents 20% of greenhouse gas damage and can easily accommodate more violent hurricanes, for now. Pakistan has produced less greenhouse gasses in its lifetime than the U.S. produces in a single year. Yet, their economy has been devastated.

If there is a glimmer of hope, it is that there is finally a sliver of recognition from developed nations of our collective responsibility. But, the problem is that economic justice requires us to remedy 150 years of spending atmospheric cash that belongs to everybody. We now understand (and scientists have known since the 1800s) that greenhouse gas emissions consume the ability of the atmosphere to live in an equilibrium it has known for millions of years and for which all our species have adapted. Never in geological history has this equilibrium shifted the temperature of the atmosphere so quickly.

Do we pay for our past mistakes based on how much we have enjoyed consuming 90% of that resource, or do we instead claim who would have thunk and require all nations to share equally in the responsibility of protecting that remaining 10%? If a molecule of a greenhouse gas is the same whether it was emitted fifty years ago or now, is it fair to now argue we each pay the same marginal cost of fixing the problem when a few nations paid no marginal costs of causing it? That is the question COP27 is now realizing, and the developed and large nations do not like the price tag.

In the end, COP27 agreed to maintain rather than blow past the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and to set up a woefully inadequate damage and loss fund. Well, it’s a start. Unfortunately, we are now more than a third of the way to 2035 where we agreed back in 2015 to limit our carbon emissions to 50% of 2005 levels. We have yet to see any meaningful reductions. And, we now have all the necessary fossil fuels in known reserves to meet demand right up to the net-zero point in 2050. Yet, oil companies continue to explore for more oil. Maybe they know something more about the dysfunction of global negotiations than we do.