Colin Read • December 31, 2022

An Economist's Assumption and a Justice's Correction - January 1, 2023

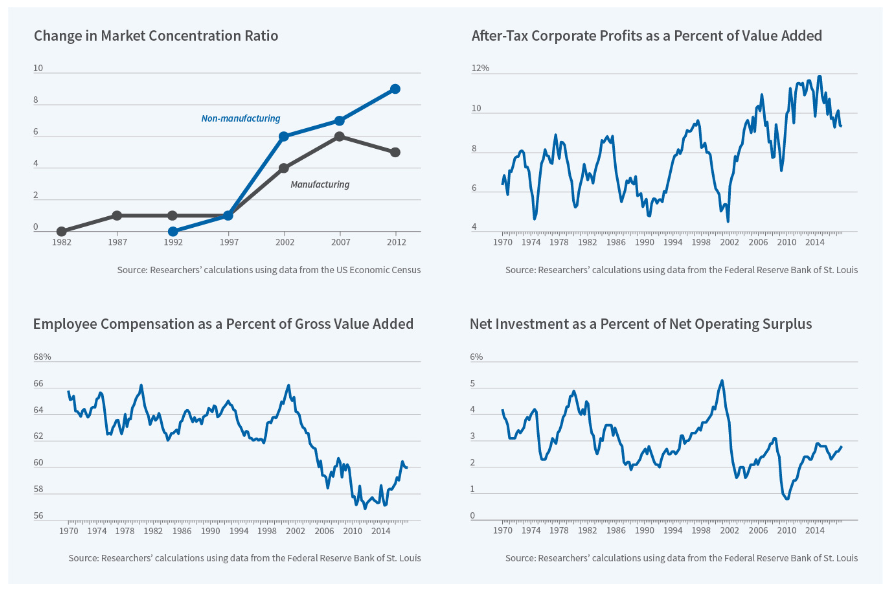

Graph from "The Economics and Politics of Market Concentration" by Thomas Philippon in the National Bureau of Economic Research Reporter, No. 4, December, 2019.

Anyone who has taken an economics class has endured the reverence for the competitive model that all economists embrace. Under certain conditions, perfect competition produces the greatest economic efficiency. That’s a pretty compelling conclusion.

There are all kinds of management goals a planner could adopt. For the last century and a half, economists have adopted the goal of maximum efficiency. The idea is to create the greatest contribution to human happiness with the least use of the resources available to us. Some have supplemented this goal to also include sustainability and an efficient ecosystem, not just a human system.

The competitive model, as described as far back as 1776 by Adam Smith, has emerged as the pathway to such satisfaction of our wants and desires with the least footprint on our environment. The idea is that a large number of entrepreneurs who compete to bring a less expensive mousetrap to market will incessantly drive toward greater efficiency until resource usage and costs can become no more efficient.

In fact, this ideal of unfettered unleashing of the competitive spirit underpins free market economies and their public policies. Unfortunately, we pin our economic destiny on a fiction.

The perfectly competitive model hinges critically on a few assumptions. First, producers take as given the prices in the marketplace, for the resource they use and the prices they can charge. Hence, the only way to become more profitable is to wring greater efficiency out of the process by using less resources.

Second, purchasers likewise cannot influence prices and constantly seek out the best value, which ultimately rewards best those producers who can provide the best value.

Finally, information is perfect and transaction costs are nonexistent. We can all easily see where the best values can be obtained and realize no barriers in purchasing from the producer who provides the greatest value.

Inherent in these assumptions is that we are all “atomistic” in that we use the information freely available to all of us but no participant can influence prices in any way. We then all collectively act to capitalize on entrepreneurship and efficiency to create value and human happiness.

This model is so compellingly attractive that its ideal is built into the American Dream. Any innovator who can build that better mousetrap or figure out a way to provide a service in a superior way will find the world beats a way to their doorstep. All we have to do is be creative, entrepreneurial, and hard-working, and we will succeed.

Every budding entrepreneur shares those values. They all embrace competition. But, then once they have made it, values change. Energy is diverted toward protecting their advantage rather than creating an advantage. Competitors strive to become monopolists who set prices rather than take them as given. The assumption that no entity has market power is replaced with the quest to expand market power.

There are some examples for which market power arises naturally. Lionel Messi and LeBron James have significant market power that earns them the status as the world’s highest paid athletes. They have natural abilities that cannot be replicated. They can do nothing to enhance their value except through their hard work. They are producing that better mousetrap.

Justice Louis Brandeis, who was on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939, observed that individuals and corporations who become too powerful increasingly attempt to accumulate power over public policy as a more expedient way to enhance profits. The ability to influence the economy through campaign donations and the resulting favorable public policy that is expected from their political largesse ensures that the most powerful producers need not worry about the assumptions of the competitive model.

These economic monoliths develop the power to lessen competition, limit output to increase prices, and ensure the most favorable treatment within the democratic process. Justice Brandeis was railing against the vestiges of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and Carnegie’s and J.P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel as these megacorporations attempted to dominate energy and manufacturing early in the 20th Century.

Brandeis observed then the all-too-familiar dance between regulators and the regulated to optimize monopoly profits. He concluded that a striving toward monopolistic power not only harms the competitive model that underpins the American Dream, but it also undermines democracy itself. Even attempts to reign in monopolies through antitrust policies often prove ineffective if these monopolies have their thumb on the scale of democracy.

The reason for his conclusion is obvious. Not only does wealth flow to those who can bring a better mousetrap to a competitive market. Power flows more so. It is this ability for economic power to then influence democracy that creates a feedback loop which permits even greater economic power. We see a taste of that with the antics of FTX that spent hundreds of millions to try to ensure their crypto empire was regulated with the lightest possible touch. We observe that Google, Facebook/Meta, and Apple can ensure that they can maintain the ability to capitalize on their intrusion of our privacy, with we, the people, willing pawns, even though these corporations would decry the same intrusion by government on our individual privacy.

Brandeis noted that a well-functioning economy must adhere to the notions that public information should be freely and costlessly available, but our own private information is a resource each of us has a right to protect. This protection is not just from government, for which the Constitution has much to say, but also from the private sector who may wish to translate our privacy into their profits.

Brandeis would be disappointed to see that the public policies he attempted to so carefully craft as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court have been eroded over time. Today our regulations focus only on the economic aspects of a corporation and disregard the political overtones. If an information technology company such as Facebook wishes to buy out a competitor, the only test is whether they can produce a better mousetrap, and hence presumably provide us with greater value, at least until they start jacking up the price of their service, either directly in subscriptions or indirectly in their ability to accumulate and peddle information about us to myriad other corporations that can capitalize on our health conditions, buyer preferences, or political affiliations.

In a December 2019 article in the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Reporter, entitled “The Economics and Politics of Market Concentration”, Thomas Philippon shows in the graph of the day that increased market power certainly results in increased profits, but it also reduces investment and employee compensation. As employers amass power and profits, employees lose power and wages. The accelerating wave of corporate agglomeration is eroding personal rights and freedoms.

What is missing in antitrust regulation as we move into 2023 is a recognition that the accumulation and enhancement of corporate influence now plays a profound role in what we always assume is a free marketplace. Society has come to accept this corporate intrusion into democracy itself, perhaps because it has evolved sufficiently slowly and perhaps because we don’t often see that a “free” service such as Facebook in anything but free.

I expect the wave of corporate mergers and the Trillion Dollar Club of corporations will continue to accelerate. In the process, a lot of potentially great innovations that threaten these monopolies will never have the opportunity to see the light of day. We need a better balance in which we all have better information about markets and the tactics that underpin them and how corporate profits influence our democracy. At this critical juncture in our planet’s sustainability, we also need those ideas that can help save the planet to see the light of day, even if they threaten the status quo the most monolithic monopolists must maintain. All we need to do is get back to the true underpinnings of the competitive ideal in which we strive for efficiency rather than market power. Where are the Brandeis’ when we need them most?