Colin Read • April 1, 2023

Banks are Suffering, But Don't Worry - April 2, 2023

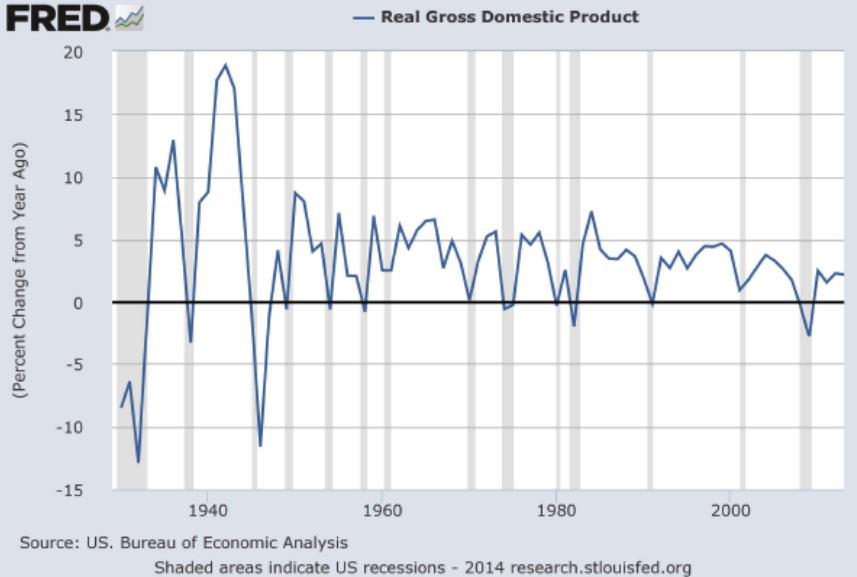

We have been dwelling on inflation for some time now. While we sometimes don’t realize the significance of any period as crises swirl around us almost constantly, we need to keep in perspective that the current inflation is the highest in over forty years.

The causes of both inflations are not too different. Both began with supply chain problems. In the 1970s, the OPEC nations, frustrated by U.S. cooperation with Israel in the 1967 battle in Palestine, imposed an oil embargo. At that time, the Middle East were major players in providing the U.S. with oil. Remember petrodollars and Arab Sheikhs in London? Their wealth grew as the forced the price of oil up, from about $15 per barrel in the early 1970s to over $60 by 1974 and over $100 by the early 1980s.

The US was growing fast, and was energy dependent. As with other economic phenomena, all we must do is think this thing through. Let us face the inevitability that if energy only represented a couple percent of our total national expenditure, and it rises seven or eight-fold, all of a sudden our overall prices will eventually rise by about 10% because a good chunk of the national purchasing power was all of a sudden owned by someone else.

If we accept the reality that our income was only to go about 90% as far as before, then we could simply endure a 10% price increase and live with it. We would need an adult in the room who would explain to us that we will have to live with being a bit poorer, at least until we develop our own oil, then that would be the end of it.

Instead, we tried to indemnify ourselves by demanding higher wages, which, in turn forced our employers to charge more for the goods we help make, until a one-time shock became a semi-permanent inflationary spiral.

What that adult in the room should have done would have been to stop prices from rising through wage and price controls. Actually, Nixon tried that, but there were more air pockets than Swiss cheese. What we could also have done was to use tight economic policy to raise interest rates and hence lower new construction, new car purchases, and new borrowing. These capital constraints would slow down economic expansion and might even cause contraction if we were even unwilling to maintain our physical and civic infrastructure for awhile.

Such monetary policy always hurts. After all, it is designed to isolate the inflationary fever, as in “feed a cold - starve a fever.” Double digit interest rates induced by the Federal Reserve for a couple of years eventually brought down double digit inflation as we all cried “Uncle.”

The same attempt to induce an inflation is happening again. We are only in the middle of ousting inflation, and we are taking drastic action, just as before, and for reasons not too different.

This inflation scenario creates two problems. The first is the creation of an asset bubble. Housing prices, real estate values, and company profits all rise with rising prices. Banks lend money to homebuyers, developers, and companies based on these artificially high valuations. They have little option. If they keep the deposits they hold in cash, the value is eroded by inflation. Meanwhile, their depositors increasingly demand higher returns on their accounts, or they will take their deposits elsewhere.

Banks eventually find that their liabilities to depositors demand a higher return, and their assets can no longer support their initial values as inflation comes down. Housing and real estate prices fall, foreclosed properties might get banks only 80 or 90 cents on the dollar, and banks become insolvent. If depositors get wind of that, they may even demand their cash, while banks cannot sell off assets fast enough, which makes them illiquid. Either can induce bank runs and bankruptcy. It takes a few years for troubled banks to become failed banks, but the inflation of the late 1970s and the monetary tightening of the early 1980s induced the savings and loan crisis of the mid 1980s.

While home prices have fallen for seven straight months recently, banks are not feeling too much of that risk yet. Instead, a huge amount of deposits arose in banks when income was maintained through government fiat during the Covid era, but with nowhere to spend it. If there were not many lending opportunities, banks instead bought the only high yield bonds that would give them the margin to be able to pay profits and the interest rate demanded by depositors.

Let’s say a bank bought a bunch of 10 year treasury bonds yielding 0.5% in mid 2020 to take account of all those deposits coming in as the government doled out Covid checks. Now, 10-year treasuries yield about 4%. Nobody wants to pay much for a bond with a 0.5% interest rate once new bonds are yielding 4%, unless a bank holding these duds is willing to sell it at a highly discounted price.

Believe it or not, such a bond would lose 28% of its value just because the Fed moved interest rates up only a few percentage points. There is probably not a bank in the country that can remain liquid if 30% of its asset value were quickly wiped away. Just ask Silicon Valley Bank.

You might say, well couldn’t they see that coming? If everybody is in the same boat and everybody is trying to liquidate their balance sheets at the same time, there is an excess supply of marketed assets and prices fall even faster. SVBs troubles become a contagion.

The banking industry works well in a steady state. It can even do well when prices are rising. When the opera lady suddenly stops singing, though, the game of musical chairs begins. Some banks are going to fail.

The Fed can do two things. First, it can avoid the mess in the first place by anticipating economic phenomena. I know you are tired of my complaints for two years now, and for the two years in around 2008, that the Fed is sometimes asleep at the switch. If only it had gradually nipped inflation in the bud early on, the more drastic high velocity policy of late would not have been so drastic and necessary. Well, that comment does not help much now (but maybe next time). So, what do we do now? Well, we do exactly what the Fed must and is doing. They are promising liquidity. They say “Bring us your weak and huddled bonds.” The Fed will exchange them for cash at face value rather than at fire sale prices. Later, when things are better, the banks will have to buy these bonds back, again at face rather than fire sale prices.

In other words, the Fed will ensure banks remain liquid and don’t have to take the 28% bond devaluation hit.

You might ask “where does the Fed get all that cash to buy back trillions of bank bonds?” Don’t ask. I mean, the Fed gets the bond collateral, and the banks suddenly get a cash deposit in their Fed account, with just a couple of keystrokes. In other words, the Fed creates that cash by making keystroke credits to bank reserves on a big Fed spreadsheet. Normally, cash creation like that would be inflationary if it translates to spending. In this case, all that cash simply translates into preventing compounding bank failures. It’s a lot cheaper to keep a bank open or force a shotgun marriage of convenience with a competing bank than to pay off the FDIC insurance for depositors in failed banks.

These problems weren’t really necessary. You can reread past blogs to see how Fed politics and complacency got in the way. The banks are paying the price, but some banks are on top of it more than others. It is too bad, though, that the banks which are more transparent and best manage risk will end up paying the higher FDIC insurance payments to bail out the poorly-managed and less sophisticated banks. It also does not help that banking and the economy are complicated, and that these economic complications are hard to anticipate by those who have the tools to make a difference. A bit of a SNAFU, but we’ll get through. Half of the art of good risk management is taking challenges face on.