Colin Read • September 23, 2022

Inflation is Overrated - September 25, 2022

Inflation Is Overrated - September 25, 2022

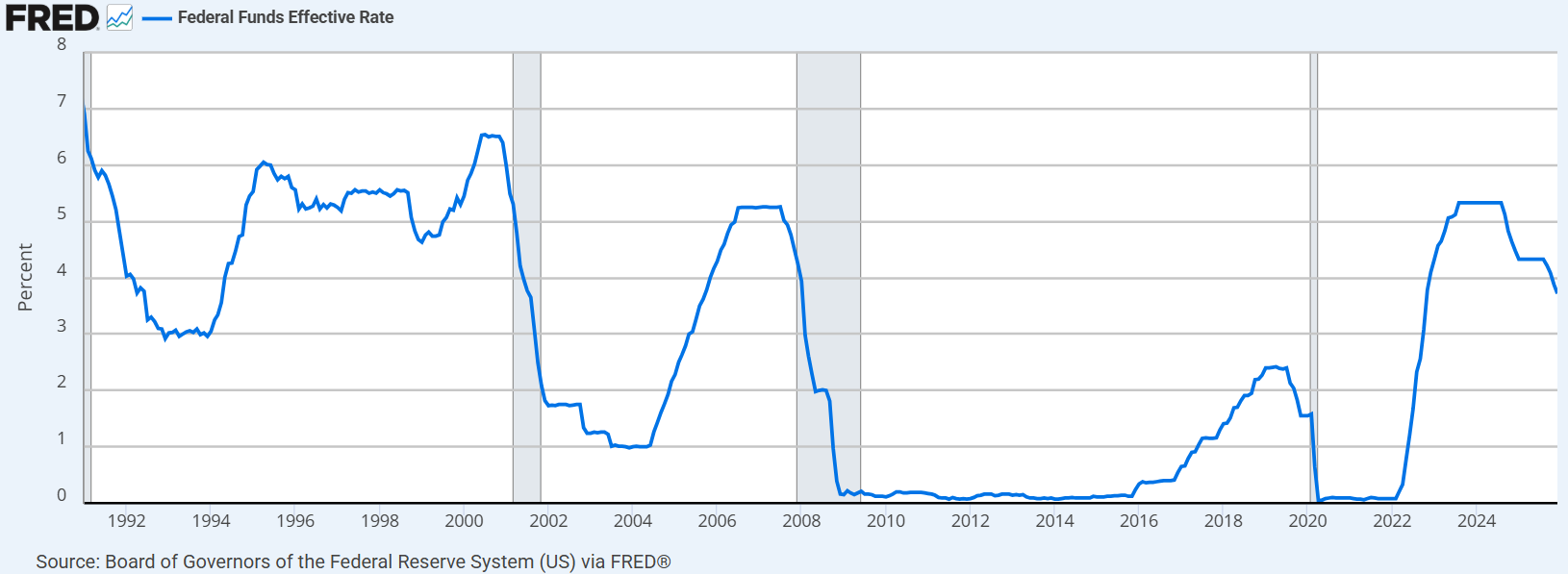

This week the Federal again increased interest rates. They probably have a few big jumps to go before they accomplish their goals. But, it may be too late. Let me explain.

Over the past year we’ve been lamenting that the Fed needed to resume its regular discount rate. This rate had been held artificially low far far longer than necessary or appropriate. Indeed, it has been essentially zero since 2008, while it usually hovers around 4% to 5%. Combined with a regular inflation rate of around 2% to 2.5%, the real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate offered banks to cover any reserve shortfalls is then 2% to 2.5%.

We are deeply underwater now. The discount rate is around 3.25% while the inflation rate is more than 5% higher, which yields a negative five percent real interest rate. This is highly problematic.

The Fed has tried to be gradualist. Because they started fighting inflation far too late, even their unprecedented series of three .75% increases in a row, they have a long way to go.

A stopped clock is correct twice a day. The Fed seems to be thinking that if they can’t catch inflation and hold it in check as it starts to rise quickly, then at least they can perhaps meet inflation when it begins to go down.

Even so, the Fed would still have to keep increasing the interest rate and have the inflation rate keep decreasing just to meet in the middle. I gave up six or eight months ago that the Fed had any chance of leading this dance.

Let’s look at the data. It tells a very different story than we are hearing from either the media or the Fed.

First, let’s go over a couple of technicalities.

The inflation rate is constructed from a survey of prices called the Consumer Price Index. There are a number of such indexes, but since most of the nation is urban-dwelling, they use the urban CPI, called CPI-U.

Next, we can expect certain jumps up or down in the CPI. When kids prepare for school, everybody goes out to shop for the holiday season, and people top off their fuel tanks for the winter heating season, we may expect a bit of a seasonal jump in demand, for instance. The CPI removes these short term jumps to remove temporary and predictable effects, up or down. This then gives us a seasonally adjusted CPI-U.

The easiest way to then calculate how much prices have risen in a year is to compare one month’s CPI to the same month a year earlier. The percent rise in prices then gives the annual inflation rate, from which one may determine an annual rent increase, salary increase, etc.

This annual inflation rate is what we see quoted at hovering around 8%, the highest since the 1979-81 stagflation.

A closer look at the data shows a couple of problems. First, prices actually began to rise quickly in the Fall of 2021. By that time, we were coming out of our COVID shells and taking care of a lot of latent spending that had been contained for a year and a half. At the same time, the supply chain remained broken, and really hasn’t even caught up fully a year later. As I wrote many times before, this was inflationary.

The advantage of measuring inflation over a year is that any temporary jumps tend to be smoothed over. Recall though that seasonal adjustments also help remove artificial bumps. We can also smooth over bumps by tracking inflation over three months instead of a year, and then converting the quarterly jump to an annualized amount so it can be compared to the traditional measure.

By doing so, we do not run the risk of being twelve or sixteen months too late before we detect inflationary problems, well too late to get ahead of them.

If you look at the annualized quarterly inflation rate, something immediately pops out. Inflation set in early in 2021, was put back in the bottle by another COVID outbreak in over the following eight or nine months, and then started shooting up late in 2021. This quarterly inflation rate actually peaked in February or March of 2022, well before the Fed began to act.

Now, I know I’ve said it hurts to say “I told you so”, but this time, it’s particularly problematic. Over the last few months of unprecedented interest rate increases to slow the economy down, the inflation rate has been uncharacteristically low and dropping fast. In fact, prices have been falling over the past few months.

Not only did the Fed not get around to closing the barn door after the horse got out, but it took about a year! What they did and are doing is way too little and way too late.

It may still be necessary though. If we all expect inflation, even if prices are beginning to decline, we will demand higher wages to retain our buying power. If we do not, we are left permanently poorer by close to 10%. If we are successful in preserving our real income, then our employers are forced to raise their prices. This positive feedback loop then creates another round of inflation. Demand pull inflation is then augmented with wage push inflation.

The Fed is then hoping to lock down any such expectations-augmented inflation. If hey succeed, it leaves those who could raise their prices (oil companies, for instance) permanently richer and the rest of us permanently poorer.

Invariably when policy makers act too timidly, bad things happen. And, invariably they do just that, despite compelling economic reasons to be more proactive. Unfortunately, the people and the politicians seem to want to replace reason with hope. That way, there is always a chance that nothing needs to change. How’s that working out for us?

See what I mean by regretting to have to say I told you so? Finding the nation in an inflation and Fed induced recession is not good for anyone (except the oil companies).