Colin Read • July 1, 2022

It's Now Unofficially a Recession - July 3, 2022

It’s Now Unofficially a Recession, July 3, 2022

We’ve been watching this train wreck in very slow motion for some time. Each new piece of economic news points in one direction only. This week is no exception.

Growth in the first quarter in the U.S. was revised downward to -1.6%. If the second quarter growth is also negative, we will technically be in a recession. I should say we are likely in a recession because the second quarter is now over, even if the data won’t be out for a month or so.

The Atlanta District Bank of the Federal Reserve publishes a real time estimate of U.S. GDP based on observation of other data closely correlated with GDP. They stated on Friday that second quarter growth is expected to come in at -2.1%, even worse than the first quarter.

If they are correct, and, as you know, I’ve believed for some time that we are in a recession, then the next question is when will it end.

A couple of quarters of negative growth averaging near -2.0% is quite deep, more severe than most recessions. That bodes poorly, and it is occurring even before the Federal Reserve’s teeth, in the form of a large increase in the discount rate, has yet to take its full bite. Indeed, many believe, as I do, that the Fed will be forced to take another big bite in July, especially when we consider that they won’t be meeting in August and have to get these inflation-deflating moves in early.

The problem is that inflation is not abating, which means the Fed has little choice but to pump the brakes harder, especially given they so delayed acting in the first place. Now they are braking in a slippery corner - not a pleasant place for evasive maneuvers.

These economic policies are more of an art than a science. More precisely, we understand the dynamics and the theory, but there are so many moving pieces that uncertainty abounds.

What is increasingly clear, though, is that households are scared. They are beginning to respond to the broken supply chain by putting off purchases, especially in travel and discretionary spending. High prices for transportation, increasingly out of reach housing prices, and escalating energy costs are having an effect on the consumer psyche.

This is verified by some of the worst consumer confidence measures in either a decade or since data has been collected, depending on which series one views. Consumers are expecting inflation and hence, like any self fulfilling prophecy, price rises remain stubborn.

At least households have stopped draining their savings to purchase latent demand and pay the higher costs arising from inflation. But, the bottoming out of savings is likely part of the hunkering down that people do when a recession becomes increasingly obvious.

It is unlikely that these forces will abate quickly. The supply chain remains broke and will gyrate in fits and starts as it repairs itself. The supply chain works best when we are in a steady state equilibrium, and does not know which way to zig when everything is zagging. Hopefully, this bouncing ball will begin to dampen, especially in light of the Fed’s newfound zeal. Meanwhile, it may be the case that growth remains negative for perhaps a quarter or two longer.

Of course, even if Washington was not terribly broken, there is little they could do until this inflation that began as a cost-push and demand-pull settles down. The Fed can cool demand, which means we may soon be halfway there. Washington missed its chance to repair the supply chain by sourcing more processor chips domestically and fixing a badly broken power grid. The lead times are long in these sectors, and the political will is simply not there to make such investments.

We are then left with the bluntest of instruments, the hope that rising interest rates will slow residential and commercial construction, purchases of consumer durables, and automobile production. We must also hope that higher inflation is not baked into the system through higher wage demands, as frustrating as it is for blue collar workers to take this most recent economic upheaval on the chin.

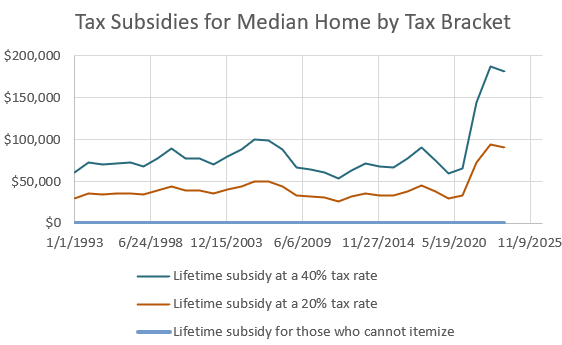

During the boom the wealthiest became immensely more so, at the expense of the middle and working classes. But, during recessions, the wealthy also manage to insulate themselves, especially if the recession invokes fear among workers. The resulting worsening level of income distribution bodes poorly for feeding the consumer engine that is the basis of the U.S. economy.

It is frustrating to see the economy spin out of control in slow motion, especially when we know there are, or more precisely were, things we could do or have done. But, that is the nature of the dichotomy between economic theory and power politics.

It may be gratifying for some to try to pin the blame for economic gridlock on a single person. Unfortunately, the blame can be spread around pretty broadly, to presidents past and current, to Putin, and to a Fed that hoped they could get through this on a wing and a prayer rather than a stitch in time.

Fortunately, the market seems to have anticipated this and has mostly corrected. Those hoping to retire soon or who are retired likely experienced a long lasting decrease in wealth, at least as measured by their shorter time horizon. Young people still have time on their side to ride this out. But, still in the wake of the Global Financial Meltdown and that recession, COVID, and now perhaps the worst stagflation since 1981, how much more must they bear?