Colin Read • November 16, 2024

It's the Economy, Stupid - Sunday, November 17, 2024

We’ve all heard the James Carville quip. Well, maybe not everybody. We’ve been documenting in this blog the economic errors the platforms of both presidential candidates have made in the past few months leading up to the election. Let’s take a different approach. What mistakes did the last two presidents make that created the frustration many voters brought into the ballot box? And what can we do to put us on a steadier path for sustained economic growth without threatening the economy with inflation? These are the questions a post-election nation must ask.

The most significant problem is an American overreliance on demand side solutions. The theory is that, by increasing purchasing power by money giveaways, consumption grows and so does employment.

The simplicity of this truism obscures economic peril. To see why, I ask you to recall some basic microeconomics.

Dropping of income into people’s pockets increases the number of consumers willing to purchase goods. People can then afford to pay for goods and services that they may have otherwise been unable to purchase. Under either interpretation, this typically results in a shifting upward and outward of our collective demand for goods and services.

The problem is that such fiscal largesse does nothing to increase the supply of these same goods and services we clamor to purchase. Suppliers receive a higher price, and that solicits some increased production. But the increased price also attenuates demand somewhat. The result is a combination of a higher price and higher output where the supply curve meets the increased demand curve, as the left hand half of today’s graph demonstrates. Output rises on the horizontal axis due to increased demand, but so does the price in equilibrium on the vertical axis.

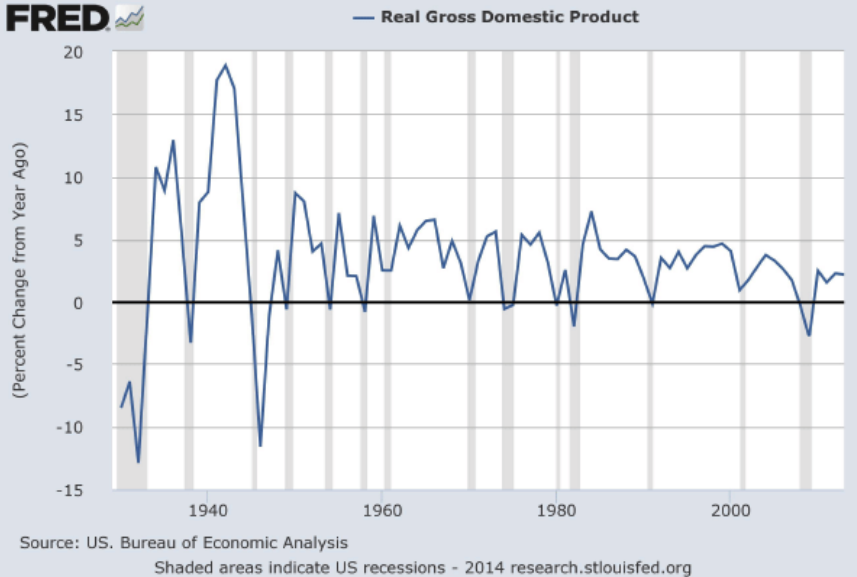

That is a problem on a number of levels. Yes, the amount of goods and services supplied and consumed rises, and hence our macroeconomic Gross Domestic Product also rises. In turn, employment rises and unemployment falls. But, since prices rise too, so does inflation. That’s the classic unemployment/inflation tradeoff. We can improve one economic variable but it is often at the expense of the other when we rely on demand driven growth.

This tradeoff does not have to happen though. Rather, it is a consequence of our nation’s chosen method to stimulate the economy by raining cash on consumer-voters and letting the free market take care of things.

As we saw recently, this unfortunate phenomenon is worsened if supply has nowhere to go. When then-President Trump, followed by President Biden, responded to COVID and its aftermath through the distribution of cash, we witnessed a dramatic ratcheting up of our national debt. With demand spectacularly and artificially increased, but also with a supply chain shut down by COVID, even a first year economics student can surmise that widespread inflation is the net result. The inflation we suffered from 2020 to 2022 was inevitable given the fiscal mistakes Presidents Trump and Biden made that compounded supply chain constrictions. The huge stimulus initiated by Trump and continued by Biden did not cause the problem, though. While they threw fuel on the fire, the COVID-induced supply chain disruption flame was already ablaze.

In the aftermath, higher prices resulted in inflation. The Federal Reserve then induced higher interest rates to combat inflation. Wages responded by rising modestly too, but not enough to immunize us from inflation. We still hear the echo of that reality. People believe their buying power has been eroded and see their savings disappear.

The higher interest rates hurt. Since our nation’s debt now well exceeds our GDP, a rise in prices and an equal rise in interest rates in the long run also increases interest payments on government borrowing and hence diverts even more of our increasingly precious savings to pay for government debt servicing. These feedback loops mostly move us in the wrong direction and result in cascading economic malaise.

While we have been documenting both the cause and the aftermath of this self-inflicted inflation, let's put our economic history in context. Some inflation due to a temporary supply shock such as COVID was probably inevitable, but the suffering and large price shock was largely avoidable. All we needed to do was to aim our economic policy at the problem rather than the symptom.

Yes, the symptom we saw was economic malaise as people lost their jobs because of COVID closures. But, what if we addressed the root problem of a collapsing supply chain rather than its symptoms?

This latter approach is sound industrial policy, and is practiced by China’s government as an alternative to demand stimulation typically practiced in the U.S. The idea is that, if the supply is constrained, or if a nation would like to increase domestic supply for strategic purposes, we should do so directly through industrial policy rather than indirectly through cash giveaways to consumers.

There are a number of ways to implement stimulating industrial policy. Government could subsidize production destined for domestic consumption without violating international trade agreements. Or, like the CHIPS act, we can subsidize building of new manufacturing facilities. The problem with targeted industrial expansion is we must be clever. It does no good to shower subsidies on an entity that was planning to build out anyway, just as indiscriminate dropping of cash into the wallets of people who would consume anyway is ineffective.

Government can also encourage research and development, a role that, again, China does intensively, and the U.S. once did much more than we do now. To be most effective in carefully targeted research subsidization, China asks, and the U.S. ought to ask, for something in return - shared royalties perhaps, to encourage even more research, or patent protection more sensible than the current 15 to 20 year duration. Given the pace of economic dynamism, such long term patent game-playing makes little sense nowadays, and holds back innovation. Perhaps 20 years of patent protection made sense in 1790, but not now.

Other avenues for increased production efficiency and a rightward expansion of the supply curve include improvements in transportation infrastructure and perhaps the leasing of land for manufacturing or energy generation at competitive rates rather than the sale of land with a price artificially escalated by speculation. Leasing of land may also be effective in reducing property taxes, which is a significant production burden in the U.S. but less significant in other nations that rely less on property taxes. The resulting expansion of earth capital and public infrastructure can significantly reduce both the fixed and marginal cost of production and hence help leverage investment and shift outward the supply curve.

A nation can also process rare earth minerals and uranium and hence ensure a steadier supply and less uncertain price for essential factors. Strategic reserves can also even out costly supply fluctuations. These savings also result in an outward shift in supply.

A well-trained labor force also reduces supply costs and shifts the supply curve outward. Rather than throw money at people laid-off during COVID, we should have mobilized a network of job retraining centers to create technical skills for a 21st Century workforce, skills that remain woefully missing in today’s economy. If a nation’s economy is at stake, is it unreasonable to encourage greater subsidization of college education in critical areas of national interest, as we encouraged more engineers in our halcyon days during the 1950s and 1960s when we were concerned about our competitive position not with China then but with the former Soviet Union. Labor cost savings through increased abundance of a trained labor force and their increased productivity improves supply.

There are other ways to increase supply and output while we also reduce prices, as shown by the right hand graph of the day. We can simultaneously increase the purchasing power of consumers without jeopardizing the entrepreneurial nature of our free market system. If we are determined to better manage the economy, we will find that our consumers’ real income actually rises. So will our savings and domestic investment in turn. This positive feedback loop will accelerate productivity and shift out the supply curve even further.

The expansion of financial capital available to invest in our collective productive capacity also increases supply. For instance, the private sector is ill-prepared to invest in large-scale sustainable energy, despite the very favorable economics of sustainable energy. The challenge with sustainable energy is the very high upfront fixed cost, and often without an efficient grid to bring that power to market. We have devoted many blogs to solutions to this supply bottleneck that arises because there is just not enough private capital and regulatory certainty to mobilize the necessary investment.

To give you an example of why the private sector is ill-equipped for very large scale energy investments, consider a current project in Zimbabwe, funded and built out by China. 1.8 million solar panels will be floated on a platform on the Zambezi River at a cost of $987 million. If the 1 GW facility can sell its power at a reasonable $0.065 per kilowatt-hour rate over a typical lifespan of 25 years, the rate of return on that almost billion dollar investment is 10%. China is providing the capital at perhaps a 4% rate, so any investor brave enough to pony up a billion dollars can earn a healthy and almost risk-free profit of 6% and still have some scrap value after a twenty-five year planning horizon. The project works only because China Energy, a state-owned investment bank, is willing to invest in Africa. They know that inexpensive, certain, abundant, and sustainable power will provide a huge boost to the expansion of supply in sectors for which energy is a significant factor of production. China expects such projects to fuel an African industrial revolution.

China is not without its own problems, though. By some measures it is already world’s largest economy, so it ought to act as such by protecting human rights and private property, including intellectual capital. It could perhaps be more benevolent in its investments abroad. And, its savings rate is actually too high. There are not enough investment opportunities to support a 40% savings rate, which translates into poor investments into unoccupied apartment buildings and skyscrapers. It must rejig to stimulate more domestic consumption, at the expense of savings, but presumably still with a higher savings rate than we muster in the U.S.

They are on the right track in emphasizing more supply side innovation, though, rather than almost exclusively relying on demand stimulation at the expense of inflation (and the resulting political instability). We can use similar reductions in the cost and increases in efficiency of our factors of production to enhance our own domestic supply chain. The longest term benefits will result when we leverage these improvements in critical industries that improve our global competitiveness rather than merely fuel domestic consumption. Investment in artificial intelligence, computer hardware and software, and nose-to-nose competition with China in the 21st Century space rate can sustain our economic growth for generations to come.

Instead, the latest economic platforms du jour seem to emphasize propping up a false economy, through promotion of financial markets and cryptocurrency, a push for artificially low interest rates without the corresponding savings of households, and with tariff games that beg for retaliation and may leave the planet in the throes of a grand trade war. These gimmicks will do nothing to expand supply in the real economy, and may indeed divert resources in the chase for tax cuts to fuel an even hotter stock market while actual investment in our productive capacity is crowded out.

It is odd that such tired go-to approaches to ward off recessions or purchase votes before elections are used over and over again, yet invariably with poor or even negative results in the long run. There are better ways to manage the economy. We need Congress and the executive branches to put petty power politics aside and do some serious analysis of fiscal policies not unlike what the Federal Reserve does before it invokes monetary policy. There’s a way, but where’s the fiscal will?