Colin Read • October 15, 2022

New Datum, Same Old Conclusion - October 16, 2022

New Datum, Same Old Conclusion - October 16, 2022

Another datum is in. Inflation ran at a seasonally adjusted rate of 0.4% over the past month.

The markets plunged because the year-over-year rate remains in the 8% range.

Let me save them some time. Even if the inflation rate month-over-month remained in the

low 0.0 to 0.4% for another five or six months, inflation will still hover above 6% and give alarmists enough of a voice to induce the Fed to continue raising interest rates and tightening the economy for another six months. This is because year-over-year measurements are merely capturing the big price runup since the big energy cost increase in March through May earlier this year.

The Fed is not raising those interest rates to expunge inflation. It has already been tampered out. Instead, they will merely be making up for their six month late start.

As you have read, even after the historically steep ramp-up of the interest rate, it still remains below its historical level. If only it had more quickly regressed back to its traditional 4-5% range long ago (well, actually, any time between 2012 and 2020), we’d not be in this predicament. The ramp-up would not merely be catch-up, and we’d be quickly converging on a softer landing.

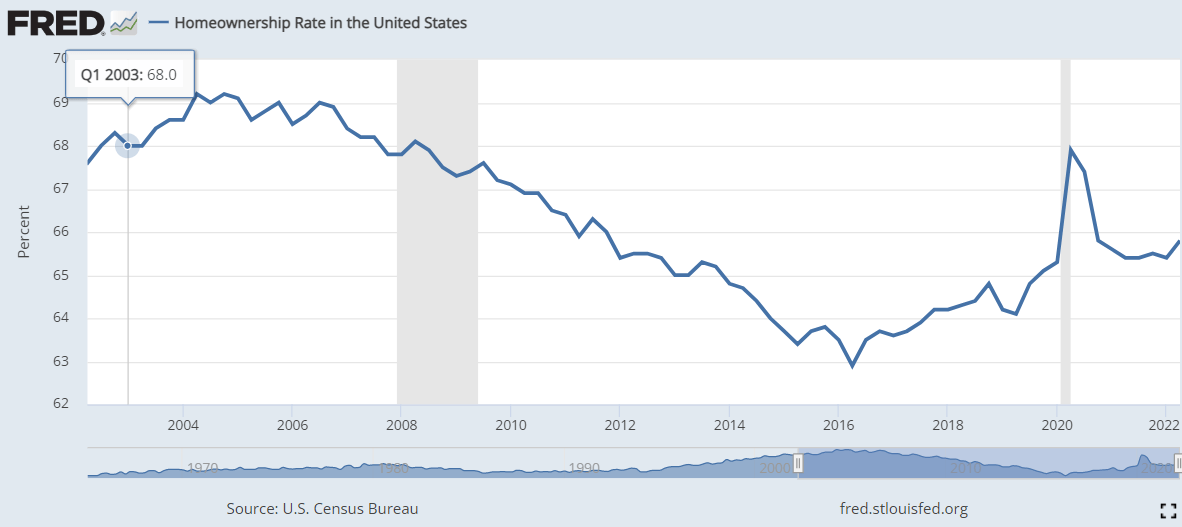

There is one shoe left to drop that could force us to endure a lot of pain yet. After a brief rebound in homeownership around 2018, people have been increasingly renting over the past two decades. A rapid increase in housing prices has pushed ownership beyond the reach of young people and young families. Now, after two years of laws that prevented landlords from evicting non-paying tenants and banks from foreclosing on non-paying mortgagees , even as governments paid tenants in the hopes they’d use the funds to pay rents, landlords are in catch-up mode. Landlords are increasingly increasing rents significantly over the past six months.

This is significant because rent is the largest spending category for more than a third of households. Yet, since renters have leases, these rent increases are only slowly dispersing across the rental market. It will take another year for that very significant inflationary pressure to be incorporated fully into the inflation rate.

Why are landlords raising rents? Because they can. Certainly, many are in catch-up after two years of inability to even collect rents. But, housing prices have been increasing over the past two years, and so too would rents under normal conditions. Normally, if rents were to rise en-masse, many renters would contemplate becoming homebuyers. But, that is almost impossible for most renters now. The most affordable 30-year mortgage rate has doubled from about 3.5% to 7.0% over the last seven years. Property taxes and insurance have also increased significantly, along with housing prices.

These factors result in a doubling of homeownership costs. Unlike the burden of homeownership for those who already own, or for those who are upgrading their housing, renters typically are right on the fringe of homeownership affordability even in the best of times. With a Fannie-Mae guideline that homeownership cannot constitute more than 35% of household income, a doubling of those costs pushes mortgages well above the threshold of affordability, and forces more renters to remain renters.

Increased housing and opportunity costs for landlords, and increased unaffordability of homeownership for renters has given landlords an unprecedented ability to raise rents. They shall continue to do so until mortgage rates come down and until housing prices moderate in the face of reduced demand.

The result is that we should not soon expect the Fed to soon end their tightening policies. I am guessing it will occur in about another six months, after the Federal Reserve discount rate has risen to around 7%, and has made many other interest rates approach 8%-11%.

I don’t expect these high rates to be reflected in a dramatically increasing unemployment rate, though. This traditional tradeoff between the interest rate and the unemployment rate seems to be as disconnected as Fed delays in responding to the obvious. But, these higher interest rates will cool down commercial and residential borrowing and new construction. This investment sector usually hovers around 10% of our economy, which is so much smaller than the 70% share of consumption in our GDP. We need to profoundly perturb such investment to replicate even a small drop in consumption reductions induced by higher unemployment.

There is nothing normal these days, it seems, in just about any dimension. When the economy is pushed too far beyond its traditional equilibrium, our ability to fine tune it declines precipitously.