Colin Read • January 5, 2024

Nothing is Certain But Death and Taxes - Sunday, January 7, 2024

We have now begun a new year. For me, it is a time to begin thinking about tax day, so today's topic is taxes. These are the necessary costs government needs to provide us with collective services that the private sector cannot or will not efficiently provide. In discussing the tax system, we must also differentiate between wealth one accumulates over time and the income one generates in a year. Our income is then taxed, and with what is left we either consume or invest to augment our accumulated wealth.

The amount we pay in taxes supports government. At the local level, the tax is primarily on wealth, while taxation at the federal level through an income tax. The differences between these two tax bases introduce some stark public policy dilemmas.

Governing is a costly affair in the United States. I almost used the term “business” instead of “affair”, but after some reflection, business is probably not the best way to view it, even if a series of goods and services are provided for a fee. But, the motivations for efficiency are dramatically different for a competitive industry than for a monopoly that knows it can raise its price at any time simply by levying higher taxes.

The tax levy is the appropriate way to look at most taxes we pay. The levy is a combination of a tax rate and a rate base. For the income tax, the rate base is our adjusted income. For our property taxes, the rate base is in proportion to the value of our home and the land upon which it sits.

Politicians find it convenient to play games with property taxes. They can claim the tax rate stays constant but they can up the value at which they assess our property. In my area, property assessments have increased upwards of 30% over the past few years while politicians pat themselves for “not raising taxes” because the tax rate has held relatively constant. But, a close look at your tax bill shows you are actually paying significantly more in taxes. To its credit, our county chose to lower the tax rate by the same amount as the assessments rose. That’s good government that our other leaders should follow.

This problem points out some of the weaknesses in our tax system. One value many hold is that we should pay taxes that are equally painful for all involved. Since poor people can afford to pay little taxes but the wealthy can much more easily afford them, our system is designed to be progressive. The income tax rate rises as incomes rise. However, if we combine that with the property tax, a poor person pays more of those taxes even if her income does not rise. That then becomes a regressive tax, especially if more affordable properties rise in price proportionally more than high end homes.

These nuances point out an interesting artifact of taxation. The federal government is funded primarily through a tax on individual and, to a much lesser extent, corporate income. But, localities are funded as a share of the value of the most significant asset most households hold. Such home equity accounts for 45% of household wealth, and most of the wealth of many senior citizens.

These property taxes can be substantial. My locality has an extremely high local tax rate. While our leaders tend to obscure taxes by calling them fees or special assessments (kind of like calling a war a “special military operation”), a fee based on a property value is a property tax. In the City of Plattsburgh, for instance, one pays a total of about 3.5% of their property value each year for taxes. In other words, after 30 years, one has paid taxes that total more than the entire price of their home. If the value of one’s home is more than two years’ income, the local wealth tax is larger than the state income tax. In fact, most people pay far more in property taxes in my area than interest on their mortgage, which places property taxes as the second highest single component of many budgets, after federal income taxes.

The tax of housing wealth is a flat tax. The rate does not change with the size of the tax base. However, since lower income households must spend more on housing than higher income households, their taxes paid on the value of their home represents a larger percentage of their income. Even renters pay a tax on housing since the property tax their landlord pays is incorporated into the rents they pay. In effect, this wealth tax is not flat, but is highly regressive, as a share of income.

It has been proposed that the federal government should rely less on an income tax and more on the sort of wealth taxes that localities rely upon. A comprehensive wealth tax of 1.7% per year could replace the entire income tax system, and would require the wealthiest among us to pay their fair share of taxes in proportion to their capacity to pay.

The wealthy enjoy many opportunities to avoid taxes. The U.S. Constitution allows state and local governments to tax wealth, but prevents the federal government from imposing such direct taxes. A quirk of the constitution prevents the federal government from raising more in a direct tax unrelated to income from one state compared to another. Since it is likely that wealth is not evenly divided per person across every state, a tax on wealth would raise more revenue from wealthy states than poor states, which would then violate the protection afforded in the Constitution. Of course, if a state wishes to tax itself heavily, that does not violate the constitution.

The wealthy shelter income not only from the ban on direct taxation in the Constitution, but also by the interpretation that only “realized” income can be taxed. Warren Buffett can make $5 billion in a good year because his investments rose nicely, and not be required to pay any tax at all on the gain. This is because he may not convert those gains to cash, and hence realize the value of an asset on paper. While our local assessor can “mark to market” the value of our homes and land each year, federal tax authorities are not permitted to mark to the market value our investment returns until we sell these assets.

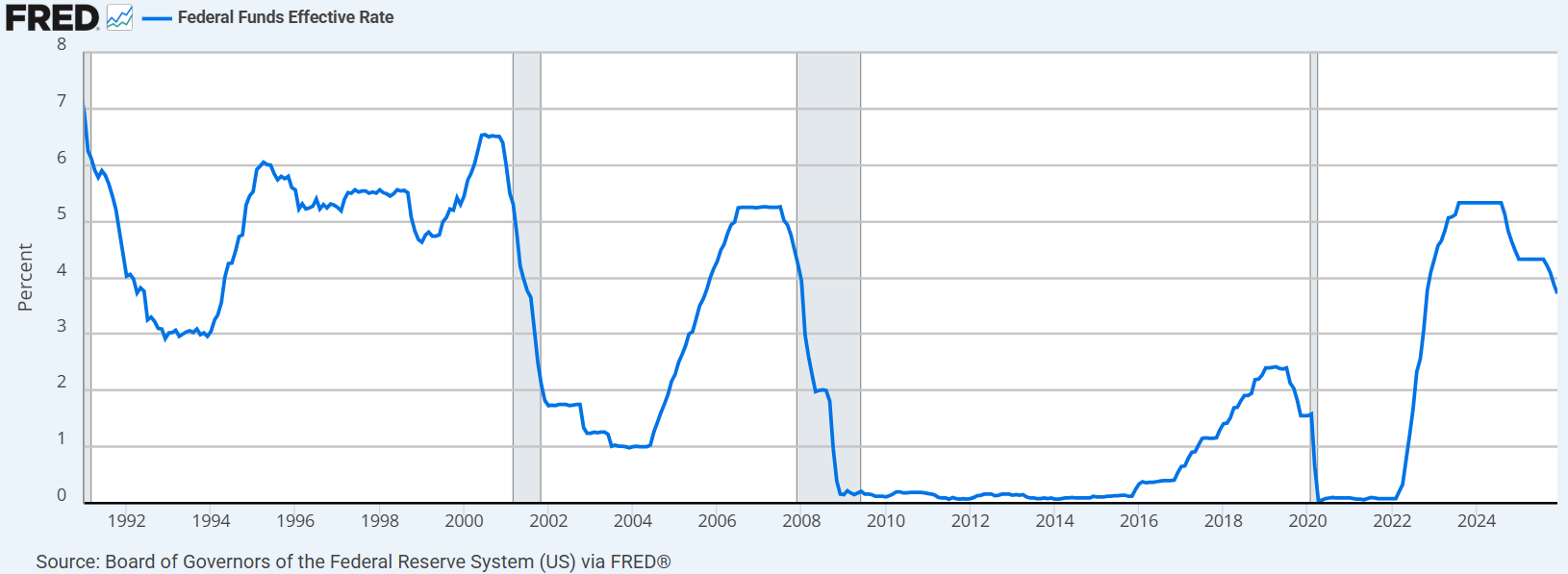

This anomaly caused Buffett to complain that it was unfair he paid a lower tax rate than his secretary. And, this does not stop the wealthy from nonetheless enjoying their income. They can borrow against their paper wealth at a very low interest rate of perhaps 3%-5%, given that their investment is backed by collateral that is easy to sell in a pinch. Since one does not have to pay an income tax on a loan, the wealthy can enjoy that borrowed income for a fee of 3%-5%, but at the same time avoid federal and state taxes approaching 45% to 50%. Then, when they pass away, the loan is paid off and the remainder of the estate can be passed on to heirs or charities at a tax rate that is zero or substantially lower than the tax on realized income, once various exemptions are considered.

The goal to make the tax system truly progressive motivates increased interest in a wealth tax. Indeed, the 19th Century economic journalist named Henry George proposed that approach in his 1879 book Progress and Poverty. He proposed replacing all taxes with a single 100% tax on increased land value, realized or not, but with no taxes on home and land improvements. In doing so, we would be unburdened with income taxes and would have an incentive to improve our homes without fear our local assessor would increase the annual taxes we owe.

Under this system, those who benefit most by economic growth embodied in land prices would pay a greater burden of federal taxation. George drew this conclusion out of frustration with land speculators and railroads who profited more on selling instantly more valuable property concessions than the income they may earn transporting passengers and cargo. But, even today, many who become wealthy do so not solely because of their own brilliance, but also because of the investment we all collectively make in the public infrastructure industry enjoys.

To rebut this taxation philosophy at least partially, some note accurately enough that there is already a partial wealth tax. If one’s wealth is derived from ownership of a company, the corporate income tax constitutes a tax each year on their earnings and eats away at their corporate value. Of course, many large corporations are able to avoid even the relatively modest corporate taxes levied in the U.S. through the exercising of a series of tax preference items built into the tax code, often after years of corporate lobbying. At least any remaining corporate taxes somewhat offsets the lack of a comprehensive tax on unrealized paper income.

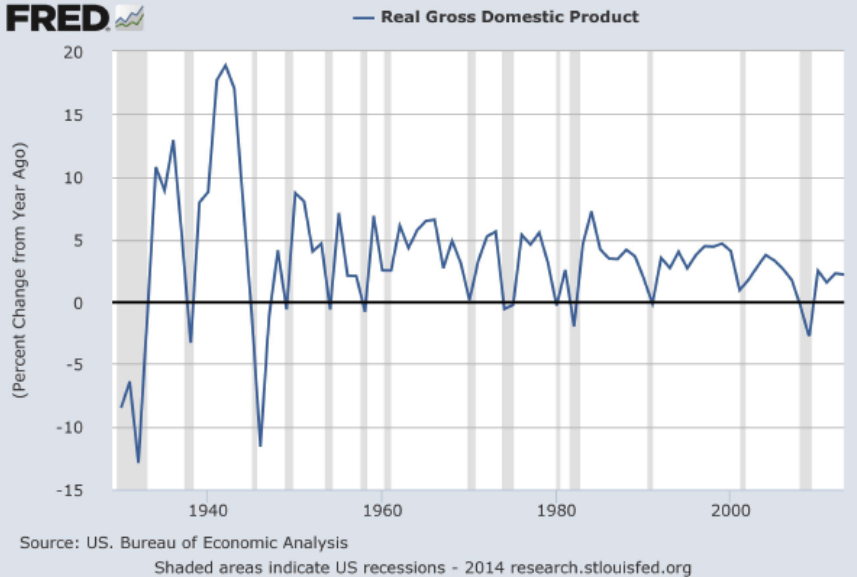

Our federal spending has been on the rise. When I was a child, we spent about 15% of our GDP on federal government spending. We zoomed past 20% in this century and are on our way to between 25% and 30% over the next decade or so. Add another 15% for state and local spending, and we see we are approaching the mark where half of our economy is spent in the public rather than private sector.

Of course, our generation has found a simple solution that works well for all alive today. We simply borrow lots of money to supplement a massive increase in spending. That way, we can keep those government payments to us coming, in a variety of direct and indirect ways, and have the next generation foot the bill. That may ease difficult economic justice decisions today, but at the expense of economic justice for our children. No worries though. The yet-to-be-born can’t vote.

Taxation is interesting from an economic and public policy perspective, and opens up opportunities for enhanced economic justice and efficiency. I’ll reserve the last word on the subject to Benjamin Franklin, who famously uttered “Nothing is certain but death and taxes.”