Colin Read • December 1, 2024

Our National Debt - Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024

Granted, we’ve had a lot of things on our mind since the onset of COVID19 and the tribulations and trials (of all kinds) ever since. But let’s harken back a little. Not long ago we were lamenting our national debt and ridiculing nations with what we thought was excessive debt of perhaps 125% or 150% of Gross Domestic Product. It turns out we live in a glass house.

There are two types of debt our federal government incurs. One is total debt. The other excludes debt the government owes to itself. Let’s first dispense with the latter.

Agencies and administrations such as social security usually take in and earn more through social security taxes than it pays out in benefits - at least until recently. For a few years beginning in 1959 when the first consignees of social security could retire with full benefits, the system ran a temporary deficit. Later, with the high inflation in the early 1980s, adjustments that raised payouts to account for inflation again meant administration took in less than it had to pay out, but the SSA quickly rejigged to balance its books. But, in 2021 the US Social Security Administration reached an inflection point. Retirement of the baby boom generation and with fewer workers coming in than retirees going out meant that the SSA had to start drawing down its savings on what appears to be a permanent trajectory.

To then, it had been “investing’ its surpluses in just about the only place Congress would allow - in U.S. bonds. In other words, temporary surpluses saved by the SSA to fund the inflation-adjusted payments it must dole out provided a ready flow of fund for which the other branches of government could borrow.

This ready flow of funds meant that the federal spending could easily exceed incoming revenues because it had a ready lender that had to accept any interest rate offered. This was as cheap a money for which any government could ever hope.

These I.O.U.s issued to fund government deficits are not considered by some to be a measure of government debt because the government could always change the rules and deny to retirees the full pensions they were promised. Or, the government could simply raise payroll or income taxes to rebalance the books. Hence, since government can renegotiate such internal borrowing, it is not considered by some to be a true measure of government debt. I disagree. The federal government is far more willing just to borrow more to replace that intra-governmental borrowing than it is to raise taxes in the future to cover up miscalculations of the past. Such past growth expectations were always predicated on a growing population. However, with a dramatically declining rate of procreation and with a sudden skepticism of immigrants, such growth of the labor force has been stymied.

Using the total measure of US debt, we see from today’s graph that the level of federal obligations hovered around $4 trillion in the 40 year post war period from about 1944 to 1984, then doubled to about $10 trillion the next 20 years from 1984 to 2004. Things got interesting after the Global Financial Meltdown in 2008. Debt doubled again from about $18 trillion in 2009 to more than $36 trillion by 2024, just 15 years later.

President Trump added about $8.4 trillion to our debt, while President Biden added about half that so far, about $4.3 trillion. This incredibly accelerating debt now represents 132% of the US GDP of $27.36 trillion.

I know, you are thinking, a trillion here and a trillion there, and we are soon talking real money.

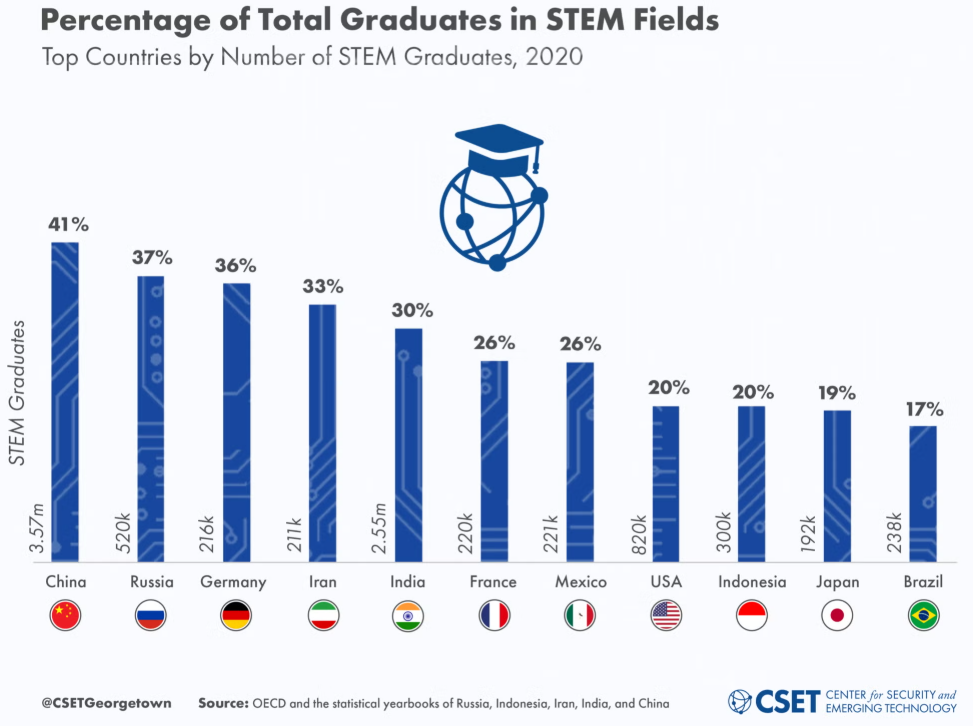

We’ve described in these pages many times before the occasional necessity to use carefully calculated government spending to make up for temporary deficiencies in spending arising from economic calamities. Such fiscal policy should only be very short term, and certainly not spanning decades, and should be carefully coordinated with monetary policy from the Federal Reserve. At times the federal government can also invest in our future through equally carefully designed investments in national and industrial policies that will provide dividends to the future generations saddled with the debt incurred. Neither of these conditions have been satisfied in the spending binge since 2017, although a fraction of the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act is helping to build out sustainable energy and bring back home advanced semiconductor production. But the vast majority of our newly incurred debt makes no such investment. Nonetheless, surely our children will be saddled with the entire bill, even though it is their parents that receive the services and the tax breaks that our politicians used as an alternative to sound public policy.

I guess we can always deflect our spendy irresponsibility by pointing the finger at other nations. After all, a few war-torn or bungled nations with tiny economies (Eritrea, Sudan, Ethiopia, Venezuela) have a marginally higher level of debt as a share of GDP than the US, only because their GDP is now so low after years of conflict. Singapore also has higher debt, but only because it invests so heavily in its global competitiveness.

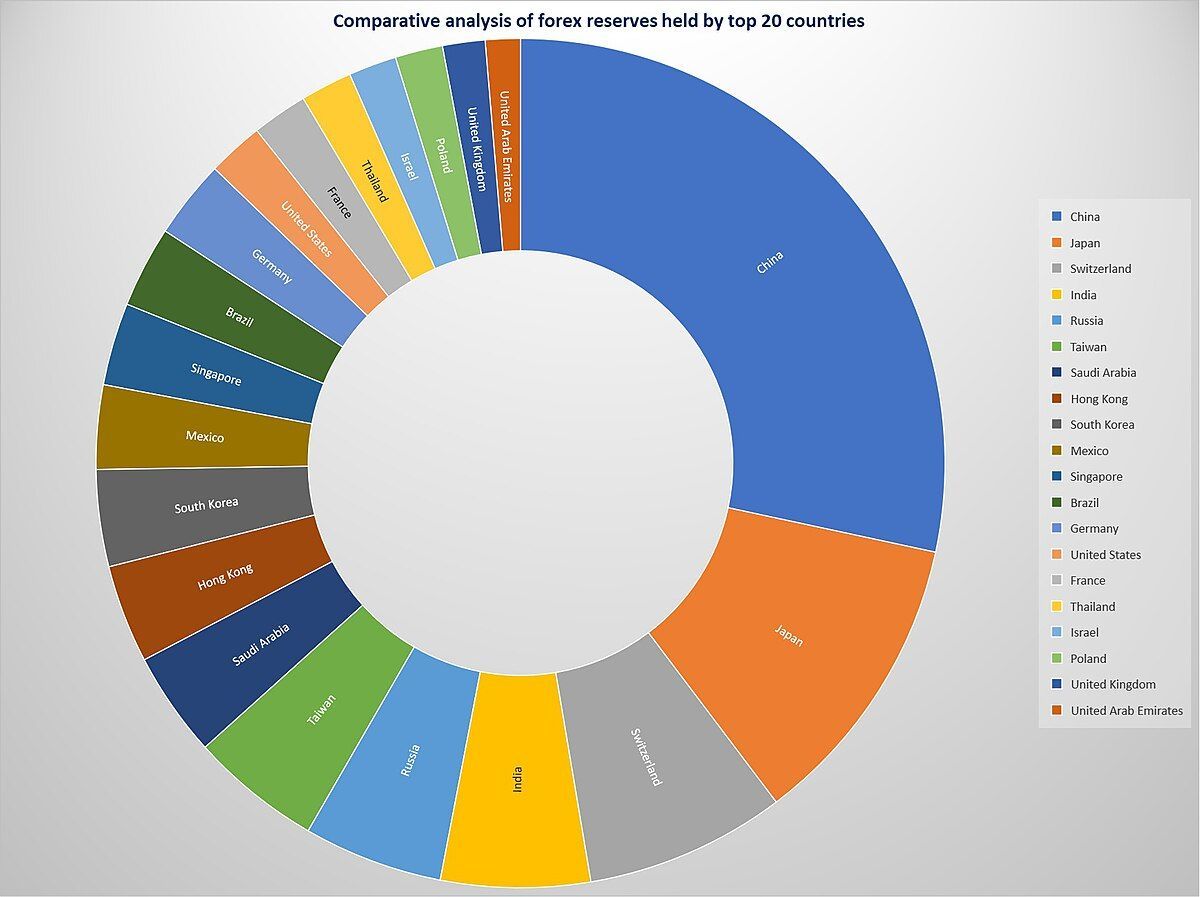

That leaves but a few major economies with a higher debt to GDP ratio than the US maintains - Italy, Greece, and Japan. The US will overtake Italy soon. At least Japan has a reason - terrible tsunamis and earthquakes, and a nuclear disaster that decimated the small island nation that has also suffered a long-lasting recession since the 1990s.

That really leaves just Greece, with some incredible bouts of economic ineptitude, and the U.S. as the nations without reasons to run such excessive spending. We will seek opportunities to share the misery where we can find it, I guess. You certainly don't hear us criticizing Greece anymore like we did constantly just a dozen years ago.

This country has become addicted to a Congress willing to spend too much to buy off one generation at the expense of those who follow. It is a tragedy that no household would be permitted, at least without the collateral to back up such proliferate borrowing. Economists would feel a little bit better if the U.S. had been making the investments necessary to ensure our kids would have the capacity and public infrastructure to pay back such borrowing. What would be even better is some sort of a plan to fix the problem. Here some talk a big game, but nobody had articulated a sincere and realistic set of policies that would fix a severe problem that accelerated dramatically in 2017 and abated only a little following the 2020 election.

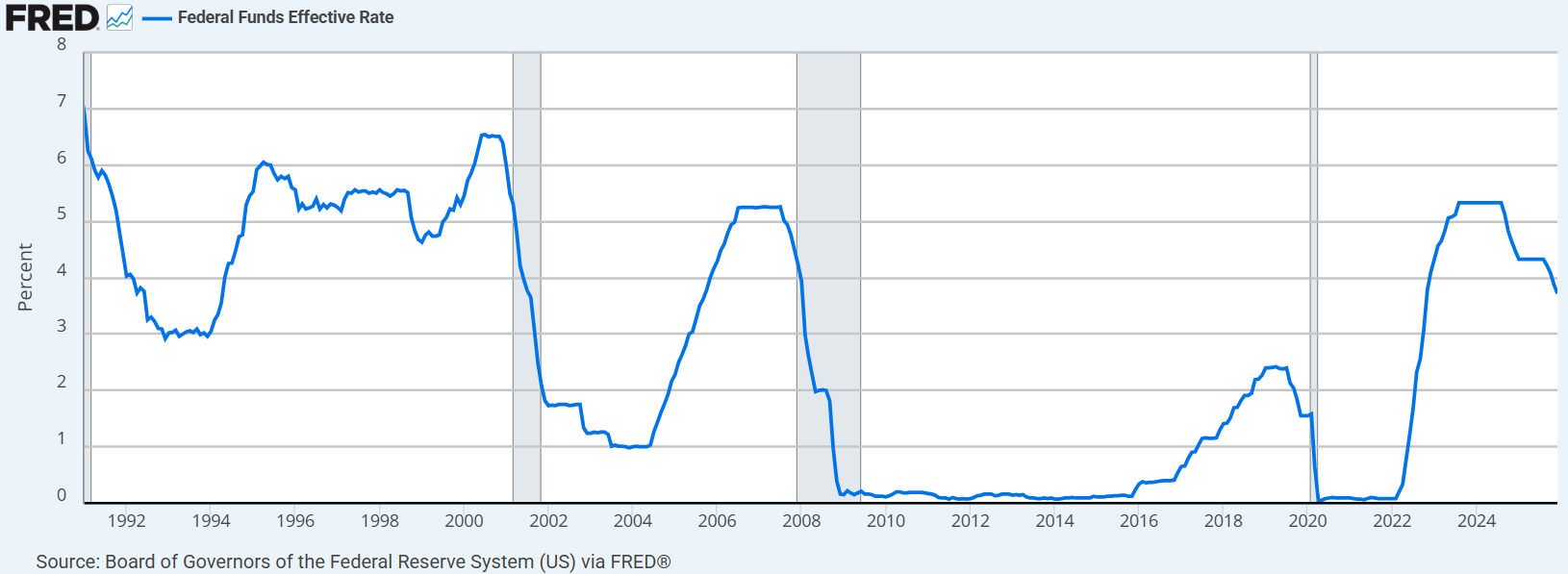

That excess spending from 2017 to 2020 amounted to about $16,000 of excessive government borrowing every year for every household in America. That is $16,000 of borrowing, year after year, now at a rate of interest hovering around 3.3% on average. We are now paying about $1.3 trillion in new debt from interest alone every year. In a few years our interest payments will surpass healthcare costs (medicare mostly) and national defense to become the second largest spending category, exceeded only by spending on that third rail of politics, social security. Should there be social security reform, as some imply but none have the courage to state, interest payments on past debt will emerge as the largest category of government spending. We can cut wherever we want but we can't do much about paying our treasury bond obligations.

Nor are we probably prepared to cut social security significantly, or national defense or healthcare costs. It appears the excessive debt train has left the station and we have reached a tipping point where we must pile on more debt to pay the interest on debt we piled on in the past. The sum total of every other category of government spending represents only a little over $2 trillion in spending, about a third of the budget. Good luck Elon and Vivek in saving his promised two trillion there. It would require closing just about every federal government branch, including border security, the Congress and Supreme Court. Let's discuss more of Elon a bit later.

The hole is getting deeper and deeper, but we keep on digging. I wish I were confident that things will soon improve.