Colin Read • March 18, 2023

Privatized Profits and Socialized Losses-March 19, 2023

There is one thing we got wrong since the Great Recession of 2008. Just at the onset of that recession, I published a book called “Global Financial Meltdown” that documented the leadup to a debacle in commercial and central banking. It pains me to imagine that, fifteen years later, we still don’t get the message.

That great recession was caused by overzealous deregulation in the late 1990s and 2000s. The idea was that sophisticated market players know what they are doing, and hence we can let them do their thing with magical new financial market elixirs that, in retrospect, even they did not understand.

The problem is that the failure of their wishful thinking was not confined just to esoteric markets for credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations. Their attempts to privatize hundreds of billions in profits required us to also socialize their losses. The Bush and Obama administrations bailed out those too big to fail on Wall Street, failed to bail out those who lost their jobs on Main Street, and promised it would never happen again - until it did.

Those who have followed these pages over the last fifteen years have listened to my complaints that the adult in the room, the U.S. Federal Reserve, too often acts too timidly and too late, and then, when they finally get around to acting, they push our economy into unfamiliar and problematic regimes.

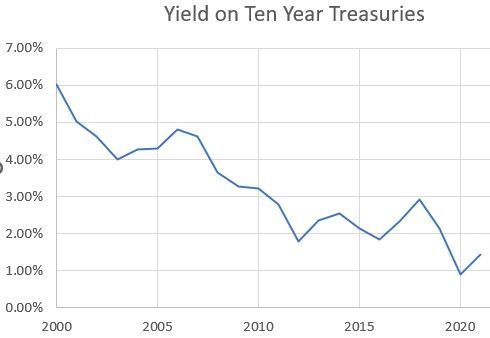

Since the 2008 meltdown, the Fed bought up toxic assets and held down the long end of the interest yield curve far too much and too long. We suffered a decade of yields on 10 year bonds that averaged 2.4% over a period when the inflation rate averages 1.8%.

In other words, the Federal Reserve held the long term real cost of 10 year investments down to about 0.6%, despite the consistent, if not spectacular, growth and the historically low unemployment rate over the entire decade from 2010 to the end of 2019.

Our economy has traditionally held the real rate of return to around 4% rather than 0.6%. The artificially low interest rate, even in times of very low unemployment, was a magical elixir that politicians manipulated to get reelected, and the Fed went along with for their own reasons too. Banks too-big-to-fail, and a smaller one called Silicon Valley Bank, with its well-connected depositors, also benefited substantially. The only people hurt were, well, everybody else.

It sounds like very low interest rates would be a good thing. It was almost as if the Fed discovered some sort of new formula that stimulated the economy but was never before attempted. It turned out that this magical elixir was snake oil.

Many knew that the Fed was peddling snake oil, but few had the courage to say so. After all, it is no fun to be that guy who takes away the punch bowl at the peak of the party. Banks too began to depend on a cheap source of funds, for which they could find myriad ready borrowers at incredibly low 4% interest rates - commercial builders, people borrowing to buy a home, those who wished to buy steadily more expensive cars - in other words, almost everybody.

Government, too, was part of this magical thinking. It could borrow at very low interest rates for fifteen years, and in that short period of time quadruple to $32 billion its national debt that had taken 132 years to build up to a quarter of that before the cheap money era.

Well, the party stopped not because someone stole the punch bowl, but because these excesses, combined with massive and mostly unnecessary COVID spending and the invasion of a European nation, drove inflation so high that the Fed could no longer pretend its invention was a Rube Goldberg device. They were then forced to very quickly and much too lately drive interest rates back up to approach 5%, where they should have been for the entire previous decade.

This caught banks out. With talk of a recession that became necessary in light of a decade of excessive monetary policy followed by inflation, borrowers ran for the hills. Even before that, the Fed’s monetary easing required them to maintain a bond buying binge that raised the price of bonds and lowered their yields. As it became more difficult to find borrowers, banks too loaded up on low yielding bonds.

Once the Fed stopped its bond buying binge, the game of musical chairs set in. Banks found themselves without any dance partners, and with nowhere to park money once the music stopped. At that time, the asset side of their balance sheets were loaded up with low interest rate loans from increasingly risky borrowers and with low yielding bonds, and with depositors increasingly expecting higher yields to cover inflation.

The business model of banks is to create high yield assets and incur low interest rate liabilities. The difference between the two, called the spread, gives banks its profits and a capital buffer to act as some protection from downturns.

Well, turn down it did. Banks found themselves making high payments for deposits while receiving low yields on the loans it extended. To compound matters, once the Fed intentionally and rapidly pushed up bond interest rates, all those low interest rate bonds banks were holding became very unattractive. These bond prices fell like lead balloons, and assets were devalued. This was so extreme that depositors of banks such as the Silicon Valley Bank feared they would lose the 95% of deposits that were uninsured. The resulting classic run-on-the-bank pushed SVB into illiquidity. Other banks, such as New York’s Signature Bank had also leveraged into crypto, and it too was unable to meet its obligations.

Many more banks are also feeling the pinch. Since most depositors realize that it is wise to keep only up to the FDIC-guaranteed $250,000 in individual insured accounts, the FDIC is the one picking up the burning bag - at the expense of the depositors of prudent banks that did not fly so close to the Sun. Again, privatized profits, and socialized losses, as we all end up picking up the tab of the banks that behaved badly.

This could have all been avoided if only the Fed had raised interest rates to traditional levels as soon as possible. As is so often the case recently, this economic peril did not have to happen. Now, the Fed is in a vice. Does it raise interest rates to sow the seed of greater economic stability and lower inflation, or does it pause, or perhaps even backtrack to bail out banks? I think it will have to do the former, but there I go again trying to do the right thing in the face of well-healed Silicon Valley investor types that want to spread their losses across the rest of us.