Colin Read • July 6, 2024

Tariffs Tax the Poor and Only Temporarily Subsidize the Wealthy - July 7, 2024

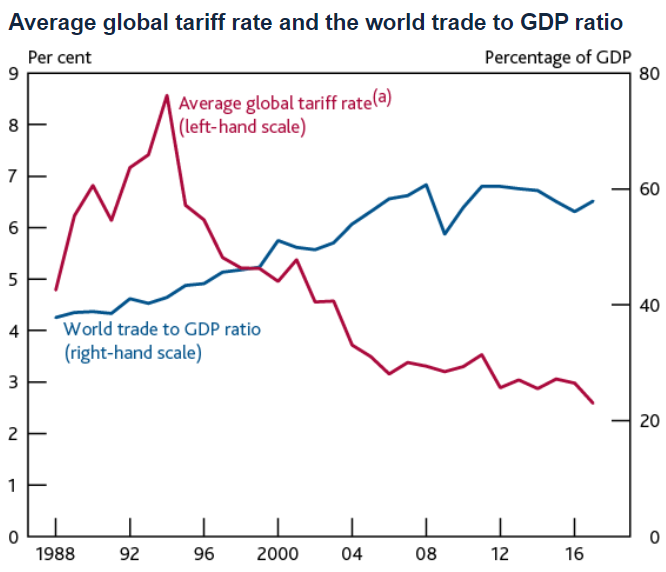

(graph of increased GDP arising from reduced tariffs courtesy of the Bank of England, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2019/november-2019/in-focus-trade-protectionism-and-the-global-outlook)

Populist politicians invariably employ trade policy to appease their masses. As are an increasing number of events in life today, such a strategy is simplistic and likely wrong, as appealing as it sounds to their electorate.

To see why, we have to look more closely into market structures. While industrial economists compare perfect competition and oligopolies, it is perhaps more useful to compare markets described by innovators and imitators.

Innovators are at the top of their game and of their markets. They develop technologies first and are able to mature new technologies faster. This gives them a strategic advantage in lower costs. They translate such economies into higher profit margins and market shares. For instance, in electric vehicles, these are companies like BYD (Bring Your Dreams), Nio, and Tesla. Battery manufacturers CATL, Panasonic, and Tesla lead the pack, while ChatGPT and Google have a large and growing advantage in Artificial Intelligence. NVidia and AMD lead the way in AI chips, Apple, Samsung, and Google in smartphones, and TSMC and Samsung in chip fabrication.

Imitators are struggling to keep up. They realize that, should they not work hard to compete, the gap between them and the innovators will only continue to grow until they go the way of the Studebaker or American Motors. Ford and GM try to imitate the leaders in EVs while a plethora of companies try to catch up in chip making, steel making, battery design and manufacturing, and AI.

Tariffs are not designed to protect the innovators. The innovators don’t need tariff protection. They already have a built-in lead and fat profit margins because they were the companies that first saw the way and invested accordingly. In fact, these companies are opposed to tariffs, even if it benefits them domestically. They abhor tariffs because tariffs breed complacency and beg retaliation.

Rather, tariffs are designed to protect the imitators who cannot compete with the innovators.

The dysfunctional dynamics of protectionism are interesting. If Tesla’s profit margin in the U.S. benefits from a 100% tariff on BYD and Nio imports from China, they may make a bit more money through expanded market share and profit margins in the U.S., but they know they will lose in the long run and in the big picture. The nations that suffer the tariffs will retaliate with similar tariffs, which will hurt Tesla in China and its economic allies, which results in lower overall profit margins even if the tariffs allow Tesla to expand its profit margin in the U.S.

Nations of innovators recognize these dynamics and do not encourage the use of desperate trade policies. Intense competition led to their success, and barriers to competition cannot be good. In fact, an innovator may be motivated by the impediments of tariffs elsewhere to become even more clever and competitive. They look for even larger cost savings to overcome the tariff barrier. They decide to source factories in Mexico to overcome U.S. barriers and take advantage of the USMCA free trade agreement. Their tactics must change but innovators succeed.

Meanwhile, imitators languish. While their profit margins domestically may rise, as will their market shares, their domestic profits come at great expense. They do not need to try so hard to innovate, so they start to lag even farther behind the innovators. They leave a trail of dissatisfied domestic customers who must now pay a higher price and for inferior cars since domestic consumers find the price of the products of innovators inaccessible. Overall, the average price domestic consumers pay rises, the average quality of what their dollars buy decreases, and the fat profits earned temporarily from the domestic market of imitators goes to shareholders who do not want their companies to further invest in products for which they already have a decided disadvantage.

Proponents of protectionism claim that such tariff protections allow domestic producers to more effectively compete. This claim may make a modicum of sense in commodity markets where innovation is irrelevant. But, these are not the markets typically targeted by protectionists. If you look at the tariff recently imposed in the U.S., they are on such innovations as found in sustainable energy technologies, electric vehicles, and metallurgical materials.

As innovators try to immunize themselves from such tariffs by setting up shop in Mexico, we will probably soon see politicians try to undermine the US Mexico Canada free trade agreement that has brought increased prosperity to all three nations. Failed protectionism often translates into increased protectionism. Only politicians double down on failed policies. A company in a competitive industry cannot double down on failure by digging their hole even deeper.

Instead, innovative nations are motivated to cultivate new economic allies and markets to replace those who wish to cut their products out, and work even harder to compete with companies in their own countries and others. Ultimately, consumers everywhere else but the tariff-inducing nations benefit, as do the shareholders of innovators in the long run.

Even the fat profits afforded domestically within a tariff-inducing nation are short-lived. The reduced incentive to innovate means that domestic shareholders of protected industries will suffer as they lose market share in other countries, competitiveness everywhere, and even market demand domestically.

In the end, we see that domestic consumers suffer higher inflation and lower average product quality for the entire duration of the tariffs in innovative industries, while the increased short term profits to wealthy shareholders are fleeting. That short term sugar high is followed by a long term low as their companies fail to compete and are increasingly shut out abroad through their complacency and tariff retaliation. Even any jobs temporarily preserved will not last if an industry is so disadvantaged innovationally that it can't compete without steep tariffs. The best use of those workers and our industrial policy is to invest in areas where we can compete rather than coddle those who can't, or won't.

The only winner in this tariff game is the politician looking for a fleeting advantage to win the next election. Wouldn’t it be amazing if we could view the world in terms of the economics that, if used wisely, can be the tide to lift all boats rather than the beggar-thy-neighbor policies of desperate politicians?