Colin Read • March 4, 2023

The Baby Boomers - March 5, 2023

We were watching a primetime network show Friday night and witnessed a local commercial for a pool and spa retailer looking for workers. It appeared that, in their desperation, the main job requirement was a pulse. A dire need of workers to keep up with demand has been the defining element of the U.S. economy.

In this blog, we have been tracking the effect of latent demand on inflation as global economies pulled out of the COVID pandemic. We have also been discussing a normalization of inflation data far earlier than the market, government reports, and the Fed have recognized price stabilization.

Yet, rising interest rates, typically employed to moderate inflation, have continued to rise, and will likely rise about one to one and a half additional percentage points before the Federal Reserve is done with its work.

And, it’s not done yet. Here’s why.

The Fed looks at a number of economic trends in its determination of the interest rate. It finds itself in a regime change. It started raising rates far too late as it misjudged tight markets in 2022. It was also confounded by government fiscal policy addicted to spending to purchase political popularity. Then, it realized it has a longer term problem on its hands which shall divide its concerns over inflation and economic growth.

One aspect of the American Dream is that we grow up, get a good education, and find ourselves working for an organization or two from within which we can be promoted and eventually retire at an age between 62 and 68, with a nice gold watch. Well, that was at least the expectation of baby boomers who were born between 1945 and 1964.

There is no such expectation of such career arcs among those Gen Xs, Gen Ys, and Millennials, though. They do not have the same sort of confidence in the workforce, steady employment, or even a solvent social security fund for their retirement. Increasingly, people plan for themselves and know only as much loyalty to the workforce as the workforce demonstrates to them.

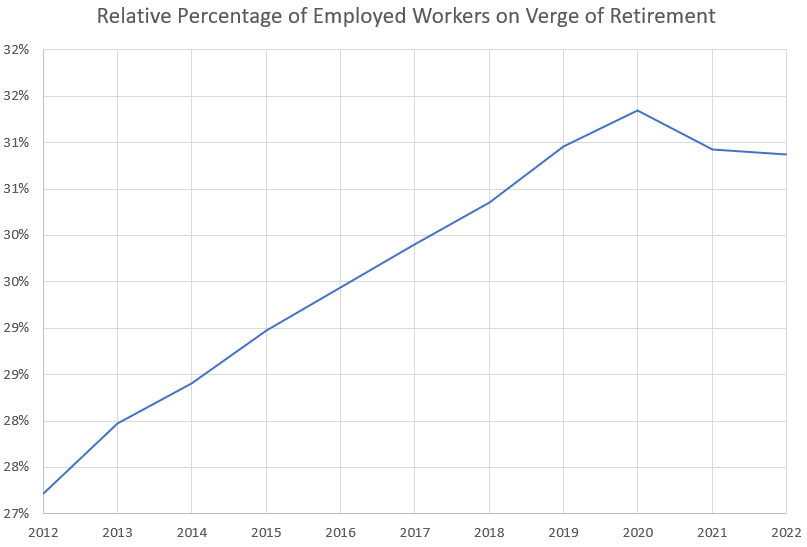

We have been documenting the plunge in workforce participation in the COVID era in which people have decided to take their job (and government largesse) and shove it. A disappearing workforce, mostly among those who can afford to leave it because they are nearing retirement or who have relatively bleak job prospects in an evolving economy anyway, has meant that there are now for the first time in recent memory far more jobs available than unemployed workers. Hence, we see ads for spa-and-pool stores on primetime television and slowed growth because businesses cannot find willing workers.

The timing of COVID is unfortunate, though. It masked a trend we shall be seeing for some time. Many attributed tight labor markets to COVID and its aftermath. Take a look at the graph of today, and you will actually see a far stickier phenomenon. The share of the workforce that is 55 years and older has been steadily climbing over the past decade and longer as the population bulge from baby boomers ages. The employed 55+ population is now approaching half of the employed under-55 population.

As these aging baby boomers retire, two things are occurring. Their unprecedented share of the labor force is causing the labor market to continue to tighten. This is also inducing a greater reliance among firms of automation and technological fixes so that increasingly plentiful and profitable physical capital can substitute for dwindling and increasingly expensive human capital.

This tendency is inevitable. As human capital becomes more expensive and scarce, companies have little choice but to evolve in their production methods. Artificial Intelligence and automation then become both a cause and a symptom of larger societal forces. The Fed is (hopefully) realizing that the economy is evolving to lessen the temporary symptom of a tight labor market. It must continue to slow the economy down to reduce the inflationary effects of this disequilibrium, as it figures out a way to deal with an inability to cultivate consumption as fewer people are necessary in the workforce.

Other nations, most notably Canada, have recognized the disruptions that arise when a labor force is pushed out of a steady state. It is managing the baby boom bulge by replacing retirees with young and well-educated immigrants. While it too had a post-WWII baby boom followed by greater population hesitancy with the Pill in the late 1960s, it realizes that are policies that can fill demographic gaps while it at the same time sows economic vitality.

The Federal Reserve and our fiscal policymakers have probably not encountered such policy dilemmas since the Great Depression, or perhaps in the modern economic era. Stagnant population growth, a dysfunctional immigration policy, and a rapidly evolving economy will be tough for the Fed to simultaneously navigate.

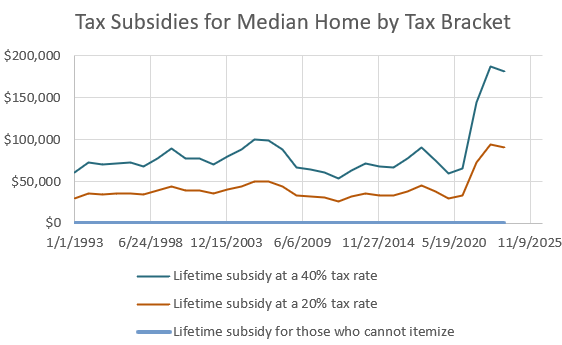

Even tougher for society will be anemic consumption growth as the size of the employed labor force continues to decline as a share of Gross Domestic Product. This declining labor income, the trend to increased housing rental as homeownership becomes more unaffordable to new entrants into the housing market, and large profits generated in relatively laborless industries all conspire to reduce the purchasing power of consumers who must traditionally devote the greatest share of income to consumption rather than savings.

We have been seeing this trend for more than a decade. At the same time, divisive government has borrowed against the future at an unprecedented rate that has quadrupled our national debt over less than a generation. In the best of times, such a perfect economic storm would be difficult to navigate. In these times, with relatively little broad awareness of the undulating seas ahead of us, I’m not too hopeful. The one redeeming quality is that our economy is resilient.