Colin Read • May 20, 2022

The Difference Between Investing and Gambling - May 22, 2022

The Difference Between Investing and Gambling - May 22 2022

The recent crypto contrived feeding frenzy begs the perennial question that seems pretty relevant now that the market has corrected in a pretty dramatic fashion. Are we investing or gambling?

The standard definition of investment is that one diverts resources from consumption today to create even greater consumption tomorrow. The money we sacrifice from today’s consumption is put to work so that an even greater amount of consumption can be enjoyed later.

Consider the root of the word “capital”. It refers to capacity, from the Latin “capacitatem.” It refers to ability or capability, in this case to the ability to produce more tomorrow by setting aside something today.

When we speak of financial capital, then, we are referring to an investment that creates additional production. In other words, our money is put to work to grow the economic pie.

Investment is then intrinsically synergistic. Investors expect that, by sacrificing today to produce more tomorrow, they shall be entitled to a share of this additional production as a way to compensate themselves for their delayed consumption. The reward we demand for such delayed gratification is labeled by economists as the rate of time preference, or the discount rate. Perhaps that is why Popeye never went along with Wimpy’s request that he would pay Popeye Tuesday for a hamburger today. For Popeye to delay the gratification he’d enjoy by lending Wimpy some money, Wimpy had to pay Popeye more on Tuesday than he lent today.

In this case, Popeye is gambling somewhat on Wimpy paying him back. There is no production created, only wealth transferred back and forth, for a price we call the interest rate.

Consider a more imaginative game to exchange wealth back and forth. We call that gambling. Instead of lending and borrowing, some bet on whether they can guess better which horse crosses the line first, which cards follow the best sequence, or which numbers come up in bingo, on a roulette wheel, or a slot machine.

This gambling may be entertaining, and obviously both sides think they can outwit the other, but nothing of value is created, the size of the economic pie is not enhanced, and our collective productive capacity remains unchanged.

For sheer entertainment value, there is nothing wrong with gambling. We must be careful not to confuse gambling with investment, though.

In fact, gambling is a negative sum game in that considerable effort and resources are devoted to what is otherwise a simple zero sum game of wits or chance between people. It is the house take, the gambling houses, or the profits extracted from the gambling of others that converts gambling into a negative sum game.

On the other hand, investing puts funds to work to start or grow an enterprise with the expectation of future production and profits to reward the investors. These investments can be risky, but must always offer the expectations of a positive return at least as great as the amount we demand to defer present consumption. Riskier projects command a greater return, called a risk premium, to compensate investors for the risks they assume.

When a company or entity sells new stock or borrows, they raise capital to enhance their productive capacity. Such stock sales would be of little value to potential investors if there was not an ability to subsequently sell their stock. Hence, stock exchanges are an essential part of the ecosystem designed to allow firms to attract funds and enhance production. However, these subsequent exchanges of stock, while they make up the vast majority of all stock sales, do nothing to raise new funds and enhance productive capacity.

These subsequent exchanges remain somewhat helpful, though, because they ensure that those holding the stock over time are those who most value the risk and return inherent in the enterprise. Such matching improves the efficiency of markets.

Between gambles and investment is speculation. Unlike the long term commitment to a productive enterprise that is the hallmark of investment, speculation is a bet between two entities about which direction a financial asset will move. It is decidedly short term, and often cares little about the value proposition behind the stock being exchanged.

For instance, much of the speculation in stock markets these days are in the form of computers running algorithms with the hope of outsmarting each other and us. These very short term bets, sometimes measured in billionths of a second, or nanoseconds, gives to this sector the name nanotrading. The algorithms care little about the nature of the underlying asset, but instead look for assets that rise and fall, or are highly volatile in the parlance of finance, so short term gains (and losses for bad bets) are amplified.

Such speculation serves no real purpose in the long run. Unfortunately, such speculation is almost invariably profitable for the nanotraders, which then depresses profits from longer term stockholders like you and me. In that sense, the reduced incentive for the rest of us to invest may even outweigh the steadying arbitrage effect of nanotrading, which converts such speculation to a negative sum game.

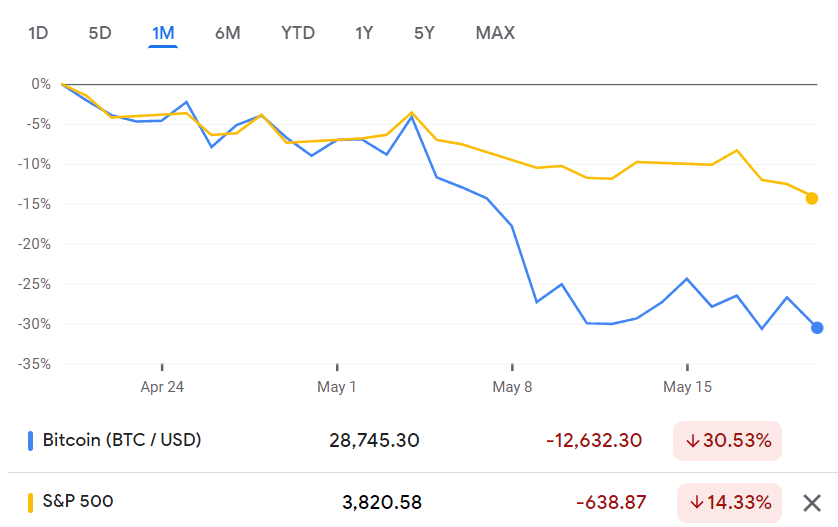

Crypto has provided a whole new level of speculation that is so easy to access by young people that many more gamblers have been brought into financial markets. I say gamblers because cryptocurrency trading is not investing. Buying and selling Bitcoin does not produce anything. As a matter of fact, considerable emotional, electrical, and manufacturing energy must be consumed to provide the infrastructure and continual mining of a cryptocurrency. In other words, crypto is a negative sum gamble of wits between those who think they are smarter than the rest.

In such speculation, for crypto or for the sale of Florida swampland by an unscrupulous entrepreneur named Ponzi, the only way that prices can rise over time is to convince more and more speculators to “invest” in these instruments.

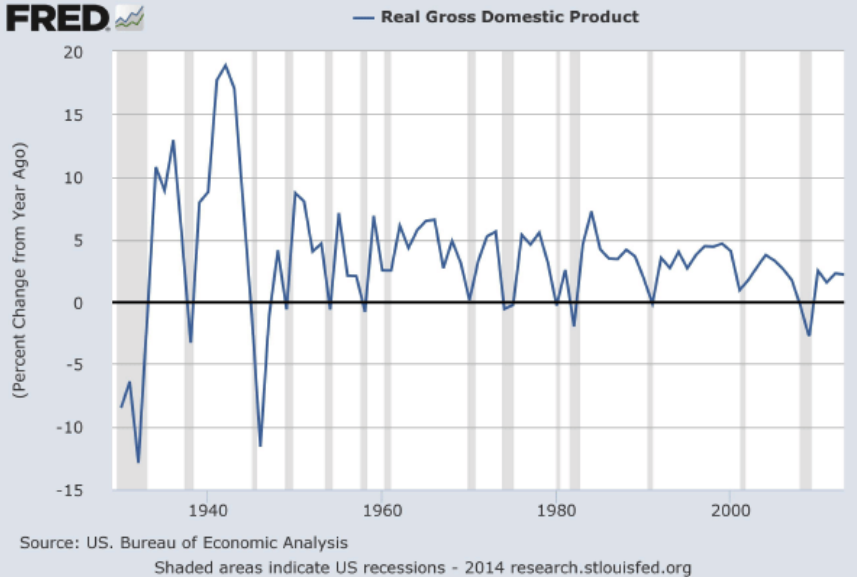

It is important to know the difference between investment, speculation, and gambling. True investments can maintain their value even in recessionary times if future flow of production can be maintained. But, once nervous “investors” head for the hills, speculative markets such as the stock and crypto exchanges can crash in dramatic fashion, as we have witnessed recently in both the stock market and in the collapse of entire digital coins.

When you invest, ask yourself what new product or capacity is being created or improved by your investment. If there is none, ask yourself if your investment allows a better match of risk tolerance for some previous investment that enhanced production or efficiency. If you can't come up with a good answer for either question, ask yourself if you are speculating or gambling, and hence your investment critically depends on people less smart than you to come later to support the "investment" you made.

Be careful out there. So long as you invest in the true sense and not the hyped version, you can ride out these storms and enjoy the fruits of a positive sum game. However, if what you are “investing” in does not produce a product and hence demonstrate a flow of new future income, don’t be surprised if you take on far more risk, perhaps even of losing everything, than you ever anticipated.