Colin Read • August 11, 2024

The Economic Resiliency of a Consumption Economy - August 11, 2024

We often marvel at the independence of the U.S. economy because it is driven by such a large degree by domestic consumption. Could that feature also be its Achilles heel? And, what is the alternative?

Keynes showed us that four forces determine the size of an economy - consumption, investment, government spending, and international trade. No economy can sustain itself primarily from investment because investment must eventually translate into sales - in consumption, government spending, or exports. And, countries that have tried to drive output primarily through government spending end up with the reduced incentives that arise because of the necessarily very high tax rate and by an institutional structure that places political decisions ahead of economic decisions.

What was less apparent in Keynes’ days of limited global trade was that the sole goal should not only be to sustain adequate economic growth. Think about your own finances. A good rate of return is nice, but we have learned since Keynes that the minimization of risk and volatility is also good.

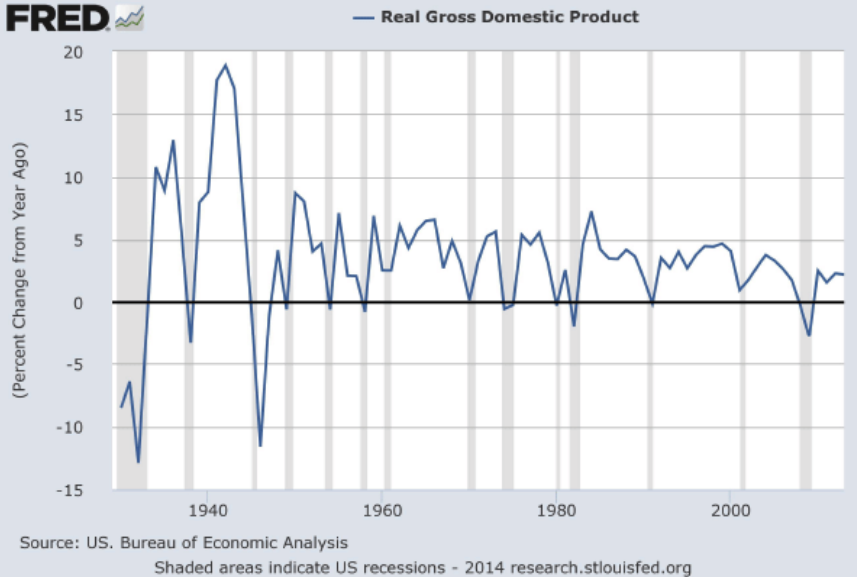

In fact, Keynes realized that economic activity can ebb and flow. After all, he developed his theory during the Great Depression, a period of prolonged economic ebbing. His solution for volatile and capricious consumption and investment was for discretionary increases in government spending to even things out and counteract insufficient demand. We can put all our eggs in the consumption basket if we have an effective policy to put Humpty Dumpty together again if it falls off the wall.

In the U.S., such is possible only on rare occasions. The Great Depression certainly commanded legislators to put aside their knives and work together to augment faltering demand through fiscal policy. So too was there a brief period of unity following COVID, even if the policies were poorly designed and ultimately led to a rebound inflation.

The problem is that the minority party rarely wants the majority party to succeed in the U.S. political system. Parliamentary systems such as found in Canada fare much better in efforts to zig with fiscal policy when consumption zags because the federal party in power can run the show if it can form a majority government.

Instead, the U.S. entrusts much of its economic destiny to power of consumption. The mantra is that consumption is so monolithic, at about 70% of the economy, that the economy can take care of itself, for the most part. But, while it may be true that consumption, and the investment that often takes its cue from consumers, can provide for steady, if no longer spectacular, economic growth over time, our reliance on the consumption sector causes us to suffer unnecessary volatility.

Returning to the personal finance analogy, any good financial planner would tell you that, by failing to diversify, you take on unnecessary risk. When we rely primarily on consumption, if consumers become pessimistic, that induces a decrease in new inventory and investment, a reduction in new home construction, reduced tax revenue, and hence decreased government spending. In other words, a reliance on domestic consumption is destabilizing because of the unfortunate feedback between consumption, investment, and poorly coordinated fiscal spending.

Trade-oriented countries are insulated from such self-induced oscillations. If exports represent a significant share of a nation’s economy, then if one trade partner is suffering a downturn, another may be doing well. The zigs of one trade component are counteracted by the zags of another. This is the same reasoning behind diversification in a personal finance portfolio. By spreading savings across many different sectors, the combined portfolio is much less sensitive to the volatility in a single sector.

Nations such as Canada, Germany, Taiwan, and Vietnam have shown strong growth and resiliency by relying not on the consumption of their population, but by the consumption of their products sold to other nations. Meanwhile, the U.S. has for decades run a trade deficit and instead argues that its economic future depends primarily on capricious nature of its domestic consumers, foreigners and trade wars be damned.

In this era of increasing American isolationism and wariness about international trade, we should instead be too wary about fickle domestic consumption, especially if we live in a nation unable to successfully coordinate fiscal and monetary policy. On our chart of the day we see that those nations most economically resilient are typically those that have a high trade openness index and a large share of their economy devoted to exports. Of course, these nations must also import a lot to allow them to excel in the exports for which they have the greatest comparative economic advantage in production.

The United States, at the eighth position, fares relatively well in resiliency, despite its low export rate and its self-sufficiency. Imagine what it could do if it renewed something that worked so well to allow its ascendancy as the world’s largest economy. It’s time to diversify the U.S. economy and renew its global competitiveness. By reestablishing its position as the beacon of free trade, the U.S. economy will discover increased stability and, in doing so, endear itself to allies in the world economy that prize liberal trade.

The hard part, though, is that investment is necessary to stimulate the export industry. And investment requires a willingness to sacrifice present consumption and instead divert those savings to investment. I believe the success of our next generation is worth some sacrifices today.