Colin Read • September 1, 2024

The Most Consequential Central Bank Meeting - September 1, 2024

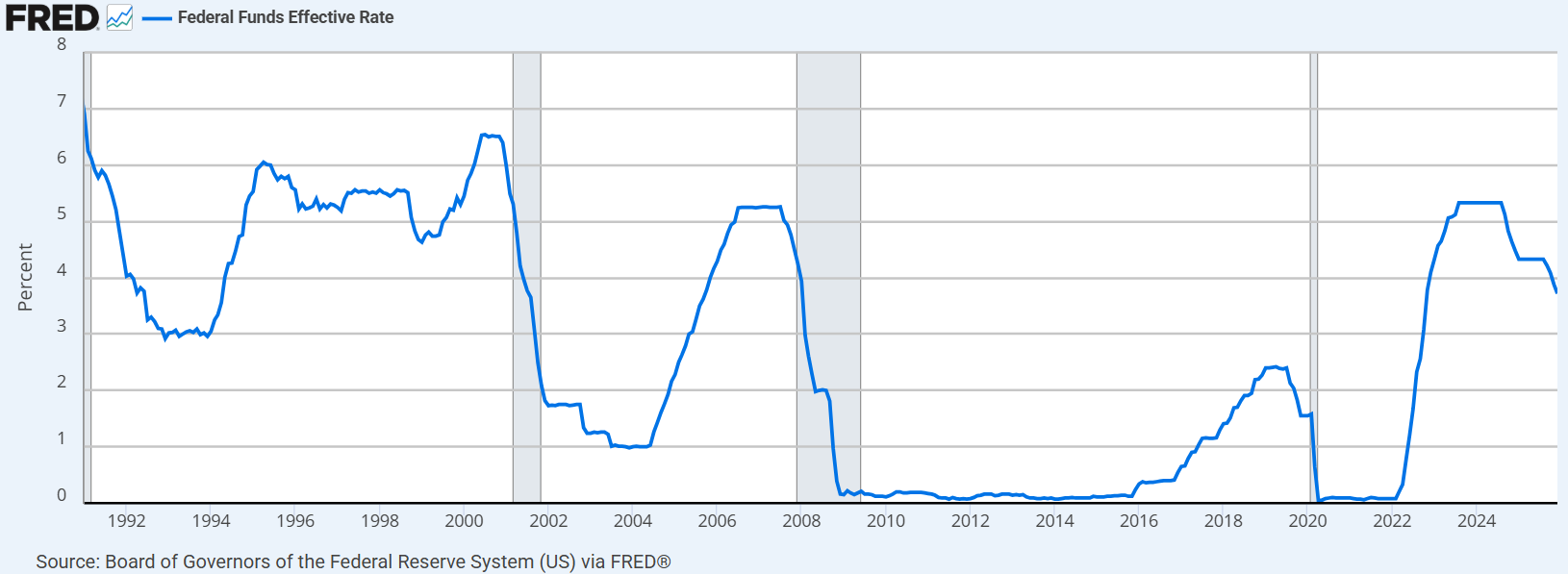

In a couple of weeks the U.S. Federal Reserve shall meet to ponder a big decision. Meanwhile, the Central Bank of Canada meets next week to do the same. These will be meetings of great political consequence and some economic consequence as well.

There are some Fed decisions that are no-brainers, economically speaking. If prices are rising too fast because demand persistently exceeds supply, and if there is a lack of an industrial policy to expand supply, then central banks learned from the 1979-81 stagflation that interest rates must rise. In fact, there is a formula that guides such increases.

Of course, we saw a couple of years ago, and in 2008, that politics often unduly influence such monetary tightening, which, in retrospect, leaves central banks with the appearance they are asleep at the switch. Sometimes decisions are hard not because they are technically complicated, but because they take courage.

The more difficult decision seems to be when to loosen monetary policy and lower interest rates. In the absence of such a well-timed policy, the economy can stagnate, people can lose their jobs, and a recession can occur. No central bank chief wants to be blamed for enabling an unnecessary recession.

That is the juncture we find ourselves at going into the first couple of weeks of September. The data is now all in, so let’s see what they do.

The most hyped data is inflation. As you know from this blog, the Federal Reserve and other central banks are caught up on a 2% inflation target. I have been arguing for almost a year that we are there. But, as you also now know, the Fed tends to look too far back and hence waits for a year before annualized inflation reads where they want it.

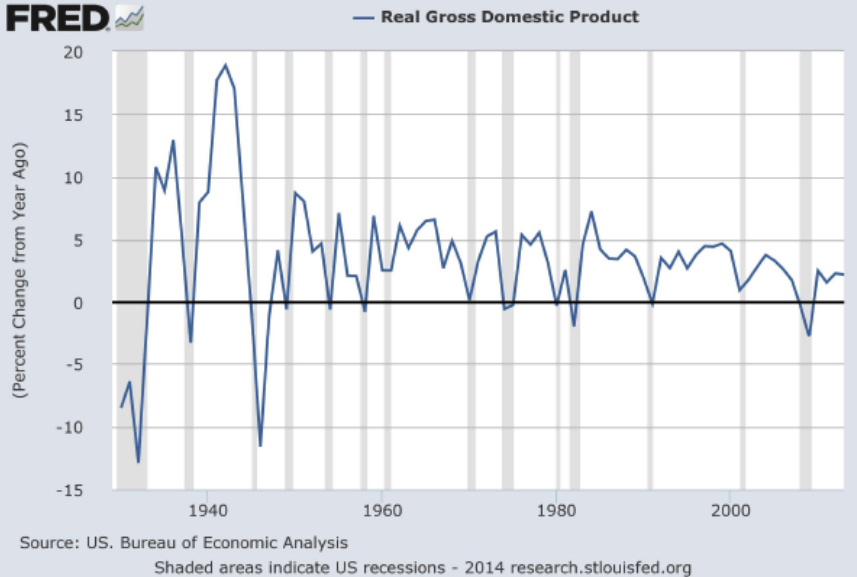

There is the policy error. There are a lot of reasons why we would be interested in an annual inflation rate. After all, we measure output and Gross Domestic Product annually so it is easy to compare one year to the next. But, increases in GDP are not an indicator of increased economic activity if it rises solely because of an increase in prices. Hence, we need to remove the price effect from nominal GDP to determine what GDP really did. Hence, a reasonable focus on annual inflation as a good GDP deflator and as a gauge to determine if our wages rose as fast (or preferably faster) as inflation.

That’s great for economic history’s sake. Such an approach tells us from where we came, but policy should guide where we should go. The ultimate economic policy instrument is the interest rate that will determine the level of real investment in the economy going forward. To focus on a past inflation rate is to drive the economic bus by looking in the rear view mirror.

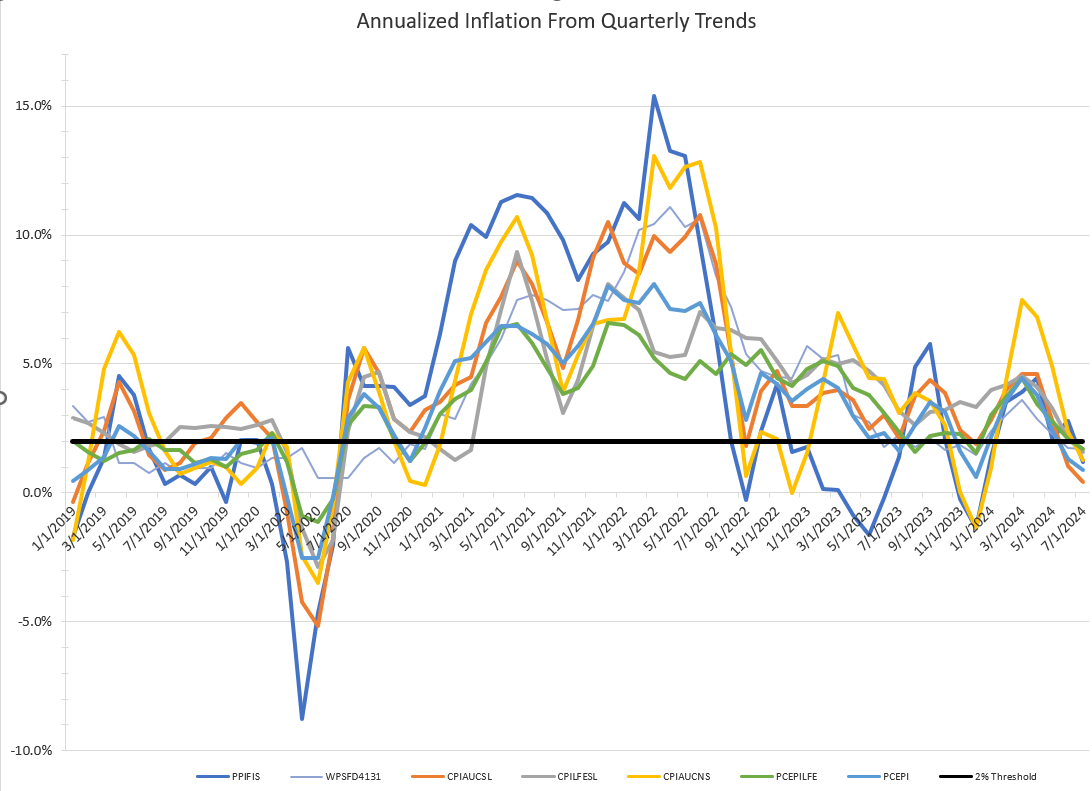

As you know, I advocate for a focus more on what inflation is doing right now, annualized for convenience and comparison purposes. Of course, inflation right now, or, more correctly, over the past month, tends to jump around a lot. Hence, it makes sense to instead ask what is the most recent inflation trend over the past few months as a far better proxy of what it is doing right now. To annualize this inflation rate requires (approximately) multiplying quarterly inflation by four, or, more accurately, calculating (1+q) to the fourth power and subtracting one, where q is the increase in prices over three months. That gives the annualized quarterly inflation rate I depict on today’s graph.

As you can see, based on that measure, the inflation rate, by the consumer price index, the producer price index, or the Fed’s favorite, the personal consumption expenditures survey, and their less volatile siblings with food and energy prices removed, have (almost) all been below 5% for the past year and a half and below 3% for the last six months. For the last few months, all measures have been below the magical 2% mark. Remember, quarterly inflation still goes back three months, so this means that prices have been consistently below 2% for half a year now. It’s time to act.

Last month we surmised that the Fed was poised for at least a 25 basis point (.25 percentage point) cut in the interest rate, and may even do a 50 basis point cut. From an economic perspective, either is okay and each would put the Fed’s discount rate at about where it usually is when the economy is humming along okay without significant inflation. In fact, over the past couple of decades, except this crazy decade and a half since the Great Recession, the discount rate may have even been a bit lower than the target I suggest.

It is not really important whether the interest rate is a quarter or half point too high, although much more than that will be a significant drag on economic activity. What is more important is the signal sent.

That is why I expect a quarter point drop but would not be at all surprised if the Fed succumbs to the politics of it all.

This upcoming meeting is the last one before the election. There will be two more meetings this year after the election, but that period will be filled with post-election noise. After that, there will be a meeting in late January and late March, way too long to leave an economy potentially languishing toward recession.

The other bit of news is what is happening with jobs. Job growth has been strong but not spectacular. If anything, job growth has been weakening a little bit, and a recent statistical reanalysis erased almost a million jobs. Hence, the unemployment rate has been creeping up just as inflation has been trending down.

If the Fed wants to send out a small signal of stimulus, then it could announce the more moderate change and hope that will tide it over for about half a year, in effect. But, the Fed may also decide to make the larger more decisive move and more aggressively steady the ship for the next six months, and, at the same time be accused of backing the incumbents in this election year. Of course, even if they took the tiger by the tail, the incumbent party will still be accused of bungling the economy so badly that the Fed had to make a strong move. So, it is not clear whether the politics of the matter are relevant anyway.

A 50 basis point move is bold, but it is certainly not unprecedented. The stabilized inflation below their 2% target and the sudden loss of almost a million jobs gives them cover. We will see the statement the Fed makes following its move in a couple of weeks. The real interesting stuff is going on through phone calls and closed door meetings, surely. I’d love to be a fly on the wall.