Colin Read • August 12, 2022

The Perversity of Prices - August 14, 2022

The Perversity of Prices - August 14, 2022

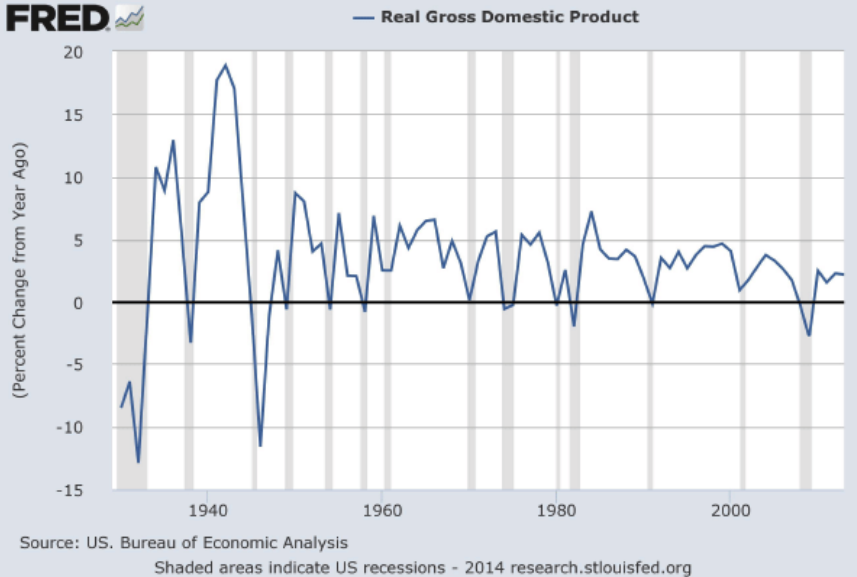

The data are in, and the story remains unchanged. The annual inflation rate since this time last year still hovers around 9%, but a reduction in gasoline prices since last month has at least moderated the month-to-month increase.

What does this all imply?

First, we should differentiate between inflation and prices. The inflation rate is simply the rate of change of a typical basket of goods and services purchased by the average consumer. This consumer price index has counterparts with the producer price index and others.

This rise in prices affects our behavior in perverse ways. If we expect inflation, it will cause us to accelerate some purchases and delay others. Certainly, on average, unless our wages rise by the same amount as the inflation, our money does not go so far. That would suggest we purchase a little bit less of everything.

For instance, with higher gasoline prices, we will inevitably purchase a bit less gasoline and drive a bit less. Most goods and services for which the price rises will see lower demand.

However, we may actually purchase more as some goods or services as general prices rise. We may be fearful that some necessary goods will rise in price still further, so we accelerate our purchases of those items we may soon need but which do not spoil. An example of this are consumer durables like appliances that will serve us for a long time.

Another category of items is what economists call inferior goods. These items are typically purchased by those with lower incomes. As our real (price adjusted) income falls, we are all a bit poorer, and hence give up craft beer for draught beer, pasta for ramen, airplane travel to train or bus travel, for instance. These more economical goods may actually see an increase in demand with inflation.

The important point is that one of the hidden aspects of inflation is that it changes not only how much we can afford to purchase, but also what we choose to purchase. Our economic behavior is modified simply because of a phenomenon of insufficient monetary policy.

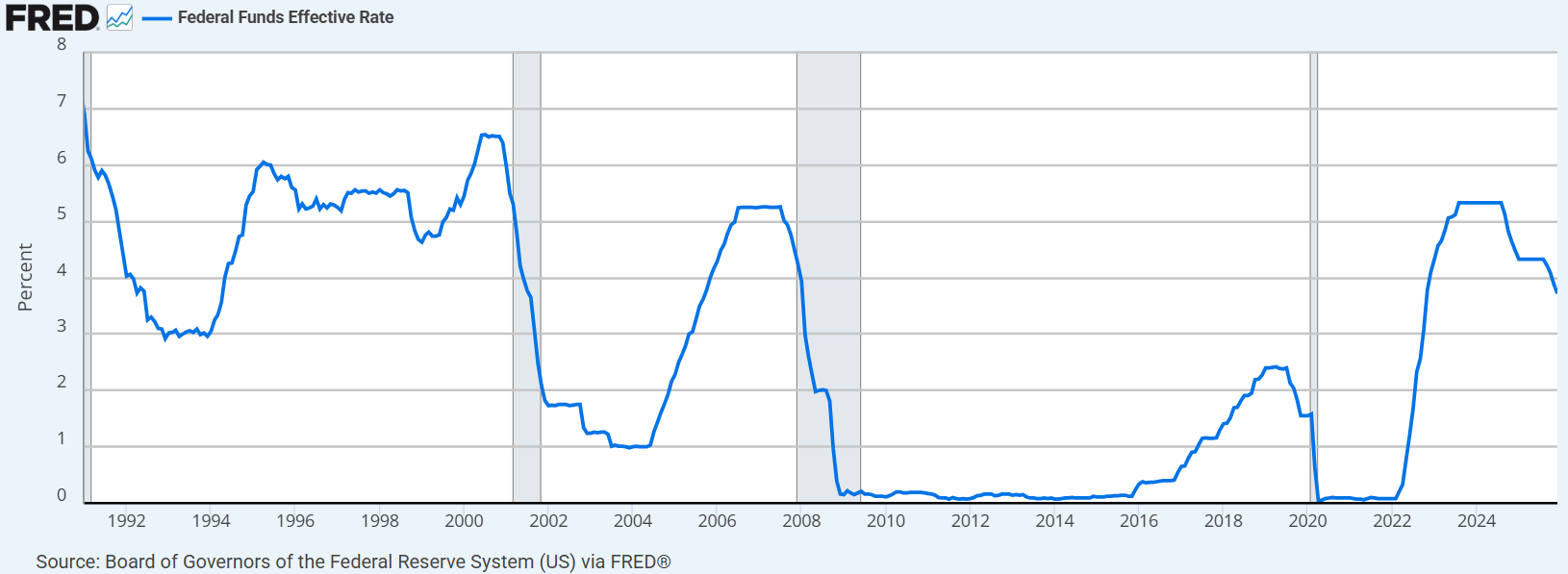

The Federal Reserve tries to keep its eye on longer inflation trends by removing the effects of food and energy prices from the inflation equation. Their “core inflation” is hence less volatile and lower than the inflation you and I see. That means they respond less quickly and fervently to inflation, which is fine when inflation is transitory, but more troubling when inflation is deeply routed, as we see now.

There is another troubling aspect of inflation, especially a prolonged inflation. It makes the economy less predictable, which has all kinds of ramifications on the supply chain.

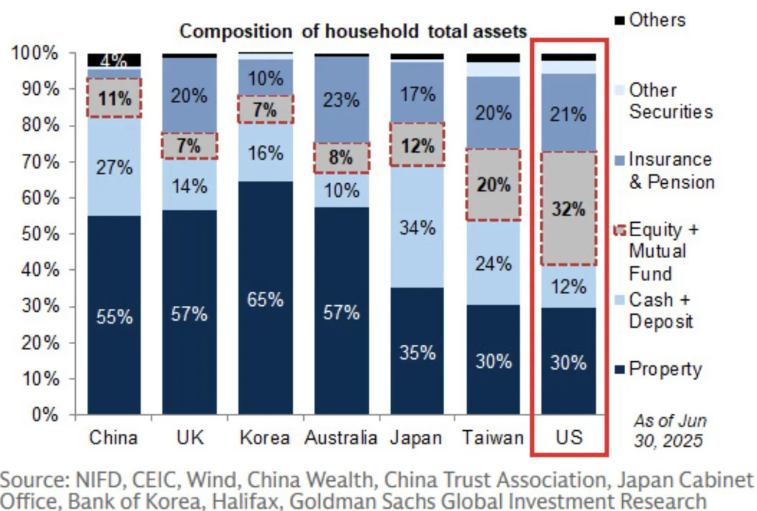

Inflation does not affect all the same, though. It much more profoundly affects those on fixed income who can no longer afford what they had normally purchased, while it may not affect at all those with strong labor power who expect a wage increase to accompany the increase in prices. Not only does inflation distort the economy, but it also widens the gap between the haves and have nots.

The Inflation Reduction Act just passed Congress today and is on its way to the President’s desk for signing. To be sure, the Act will do nothing for today’s inflation, except to perhaps reduce the expectations of inflation by some. A bit of hocus-pocus perhaps, but it is true that expectations are important. Nonetheless, the name is a misnomer.

That is not to say that the Act is not good. Our economy has been investing far too little into infrastructure for decades. Our electric grid is woefully inadequate for the geographic pattern and size of sustainable energy investments in wind, solar, and storage in pumped hydroelectric. Already, sustainable energy is significantly cheaper than any other new energy supply, including natural gas and coal. Properly amortized, it is even cheaper than the operating costs of existing fossil fuel plants.

The Act will increase sustainable energy supplies and most all economists accept that, over time, energy prices will fall, or at least won’t rise so quickly. This is the anti-inflationary aspect of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The Act is also redistributive. It pays for these savings by taxing those large corporations who are able to evade taxes, and for corporations that enhance shareholder value by purchasing back their own shares when the stock price is low. Generally speaking, those who own these corporations are also wealthier and more insulated from inflation. In doing so, the act actually stimulates demand overall, and puts an upward pressure on prices, by increasing the purchasing power of lower income households.

In that redistributive aspect, the Act may be less anti-inflationary than the title suggests. The Act does far more good overall though. If anything, while very significant for a nation that has been notoriously unwilling to invest in public infrastructure and mitigate the economic risks of climate change, there remains so much more that we must do.

Finally, the ability of Medicare to negotiate drug prices will not be implemented for many years to come. This measure will help drive down prices eventually and, while significant for some, will only have modest effects overall. Still, a rebalancing of pricing power will help counter the extraordinary power of large pharmaceutical oligopolies.

Next week’s theme, barring any jarring new economic news, will further explore the soundness of significantly larger investments in sustainable energy. There is a growing consensus among economists that these are the dollars most wisely spent.