Colin Read • October 14, 2023

The Veil of Ignorance and the Rights of Peoples - October 15, 2023

We all sit in relative comfort reading this blog without fear of invaders entering our house, or worse. Our safety and security arises because we live in societies that guarantee certain rights. Not all, and perhaps not even most, of the peoples of the world enjoy such a privilege, as we witness in the Middle East today. Our economies are moving toward wartime modes, and the promise of economics is depreciating.

The economic rights we enjoy are maintained because we each accept certain premises as universal. Certainly economics is the formal study of enlightened self interest. Well before the creation of the discipline I practice and apply, philosophers have weighed in. Even the Bible, in Matthew 25:40, stated “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” It was a recognition that we can only pursue our own self interest if we also demonstrate concern for the rights of others, especially those of the weakest among us.

Our parents even taught us that lesson. When brothers and sisters clamor for a bigger piece of a pie, our mothers or fathers may have let the oldest sibling slice the pie and then let the others pick their pieces. That way, we are ensured of a modicum of economic justice.

The great Harvard philosopher John Rawls articulated the need for each of us to regard the rights of others in the pursuit of our own rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Within a group of people we may label a nation, he argued for a unifying principle for public policy called the Veil of Ignorance. Under that veil, policy should be designed not based on how it affects those who are most powerful, but how it may affect society for the greater good.

Rawls described the danger of formulating public policy based on our

original position. If each of us cannot put our narrow self interest aside to establish principles for the good of all humankind, we engage in a constant churning of coalitions of those with similar original positions, defined by our affluence, our education, perhaps the region where we live, rather than our common good. The coalition with the greatest power then makes the rules that affect us all. This inevitably causes us to covet, guard, and, if a member of a successful coalition, expand what we have at the expense of others. Rather than baking and growing the pie, we try to expand the size of our slices at others’ expense. That’s politics.

If, instead, we as a people, apply a more enlightened view of policies, we may try to imagine how a policy can detract from others rather than how it can benefit ourselves. We have public education because we recognize it is good overall, even if we opt to educate ourselves in the private sector. But, those who can afford a private education sometimes lament that they should not then have to pay taxes for the education of those less fortunate.

Humans have a hard time setting aside our original position. I constructed for my students a thought experiment I call a baby lottery. Let us first acknowledge that a baby is, on average, average by nature, although how she or he is nurtured can make a great difference. Imagine when you and your spouse may have looked forward to delivering a baby. You did all you could to create the best prenatal environment for your future child. You both go to the hospital to deliver, and all goes smoothly. The new mother and father are given a few hours to rest after the delivery while the baby is measured and weighed and tested. On your way home, you swing by the nursery to pick up your precious baby. When you ask, they give you the closest baby to the door. You inquire whether that is actually the baby you conceived. The nurse explains that it could be, but that, statistically, you created an average baby, and, statistically, the baby handed to you is average too.

Most of us would object to this bargain. We all believe our baby is exceptional, just as all children in Lake Wobegon are above average, and we are all above average drivers. But, if we are willing to set aside our individual exceptionalism and become unwed to our original position, we would very quickly agree to many new social provisions, such as guaranteed access to prenatal care, requirements that mothers refrain from risky behavior during their pregnancy, and superior public education.

It is clear that few peoples, if any, are willing to set aside our individual original positions, although some societies enshrine the rights of their weakest more than others. Nonetheless, Rawls’ idea is thought-provoking. After that success, Rawls asked himself whether there was a universal analogy to his veil of ignorance.

Rawls concluded there is not. He noted that only a peoples within a nation who agree to be governed in a particular manner can impose such a principle among themselves for their greater good. We must make a decision to participate within a nation, so a nation can only impose such a standard within its borders.

With this observation at hand, Rawls established sovereignty as the comparable international standard. A nation is free to adopt the standards to be applied within its borders, but can do no more than negotiate contracts, called treaties, for standards of behavior beyond its borders. These treaties can also be discarded at any time, but the only sanctions we can impose internationally are economic.

His principle is the essential importance of sovereign borders. It may mean we may very much detest the way a nation governs itself, but, so long as it does not tangibly and immediately violate the sovereignty of its neighbors, it must refrain from aggression. Economic carrots and sticks are fair game, but military provocation is not, and must be met with strong defensive actions.

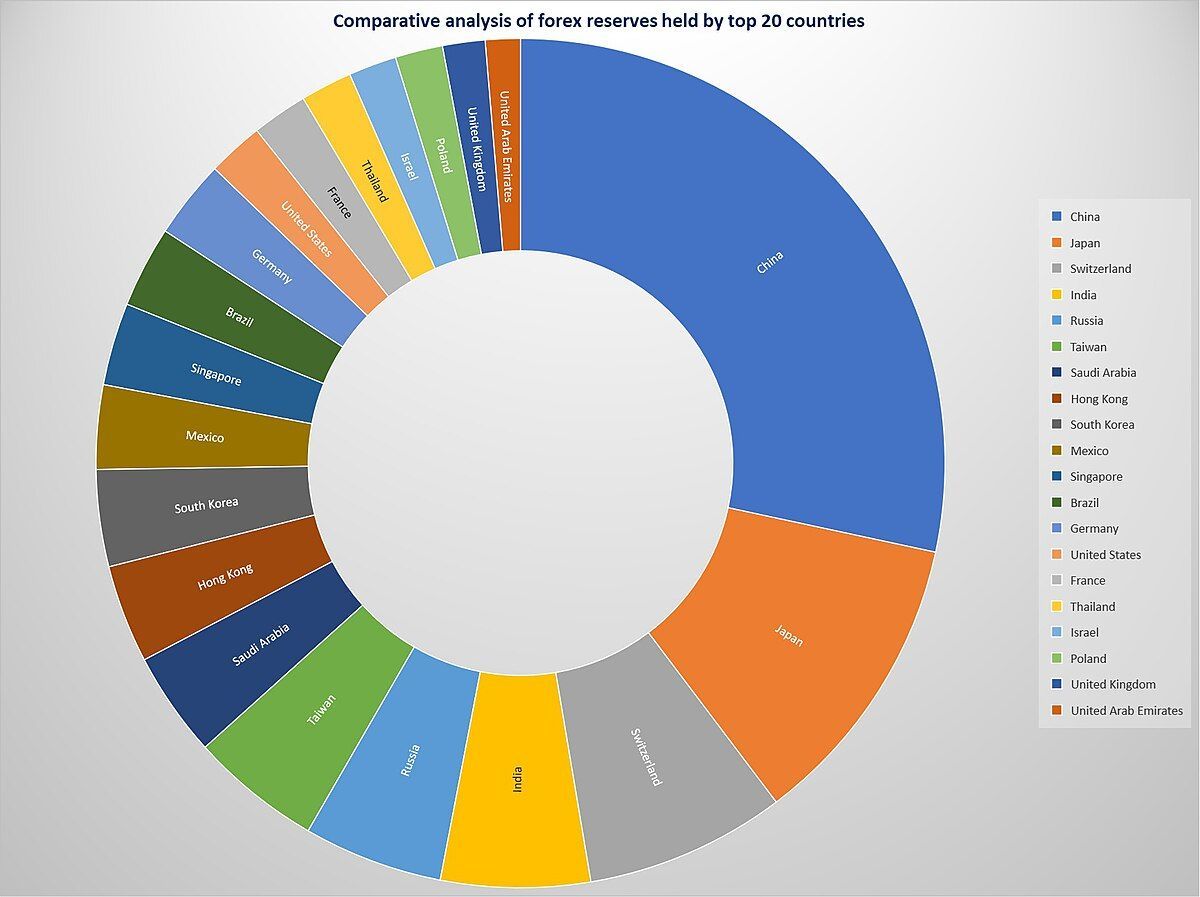

This leaves groups such as the United Nations with the primary goals of maintaining sovereignties, discouraging invasions large and small, keeping the peace, and negotiating treaties and principles that protect the rights of our collection of nations. These may have been founding principles, but vetoes that can be exercised only by the world’s nuclear powers, and the reduced effectiveness of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in the wake of newly forming coalitions of nations, have diluted these principles.

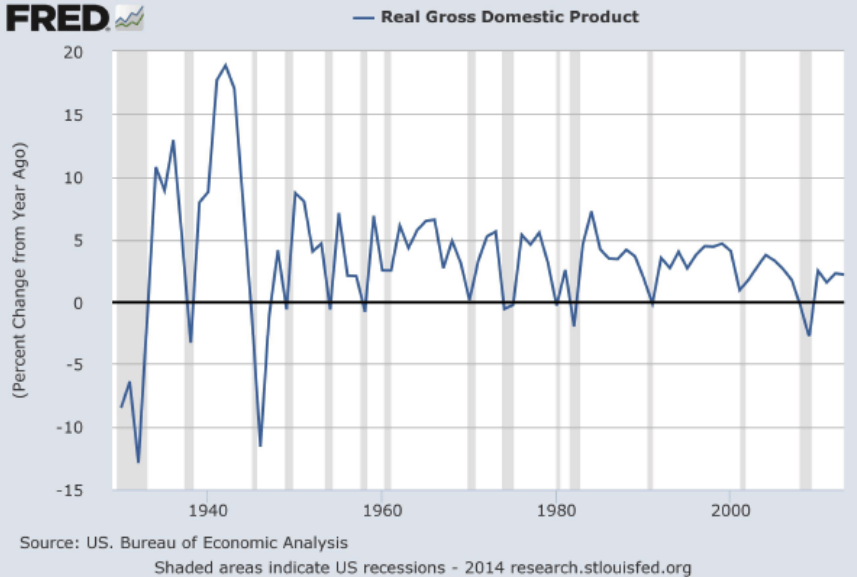

I was a child of the 1960s. But for the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cold War fears of major war was abating. The Doomsday Clock margin of seconds to midnight improved after the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and breakup of the USSR. We were promised the peace dividend that children of the 1960s all imagined would be possible in our lifetime.

Instead, the Doomsday Clock has worsened ever since the 1990s, and is at its worst point ever now. The lot of all peoples of the world seems to be worsening rather than improving. Borders are not sacrosanct, and the U.S. recognizes threats in the Middle East, Russia and Ukraine, China, North Korea, and more regional violence and threats in Africa. As we discussed last week, the U.S. does not have the economic tools following the internationalization of economics in the wake of the Yom Kippur War and the OPEC oil crisis. Power and policing is dispersed, and the United Nations is unable to fill the vacuum.

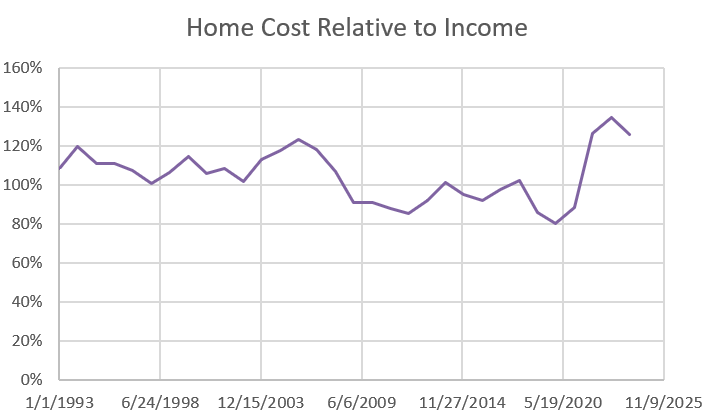

In this environment where sovereignty is breaking down and sanctions can so willingly be evaded, we are left with a free-for-all. It is not surprising, then, that wars with broad international implications have broken out in Ukraine, Israel, and Palestine. When borders are not respected, or when peoples such as the Palestinians cannot secure sovereignty, we reap what we sow. The justification of invasion is often that they are trying to protect their borders, but with each expansion comes a longer border to protect. We are left with the greatest tragedies and war crimes we have witnessed in recent history. The suffering of civilians in Israel, in Gaza, in Ukraine, in the U.S. around 9/11, and in Iraq, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Yemen, Syria, Pakistan, and many other places is tragic.

The UN reports that these wars which followed the War to End all Wars typically kill ten times more civilians than soldiers. Soldiers on the pointy end of the spear aside, our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is becoming more distant, just as the Doomsday Clock clicks closer than ever to midnight and our peace dividend is quickly disappearing.