Colin Read • February 3, 2024

Vermont Better Lawyer Up - Sunday, February 4, 2024

Vermont is determined to be the laboratory of progressive policy in the U.S. They have a moderate Republican governor, but both branches of their legislature have veto-proof Democrat/Progressive majorities. I hope their Attorney General is ready for some trips to the Supreme Court, but I wish them well.

A pair of initiatives in the Green Mountain State are attempting to lead the way in ways that the Federal Government either can’t or won’t replicate.

The first is a wealth tax. Vermont, in a pair of bills currently winding through their legislature, would impose a tax on any addition to wealth in a given year, even if it is not in the form of cash income received. One bill would extend the state income tax to half the capital gains on wealth for those with a net worth more than ten million dollars. In any regard, this tax would be capped at 10% of their net worth.

A second bill would add a surcharge of 3% to any income earned beyond $500,000 in a given year. This latter surcharge on high income individuals is not unusual. New York has imposed surcharges on the income of the wealthy in excess of $5 million.

These Vermont taxes are estimated to augment state coffers by about 10% of approximately $1.1 billion in personal income taxes paid in the state, but would be equivalent to about a 30% increase in taxes levied on the 3,500 households earning more than half a million dollars per year.

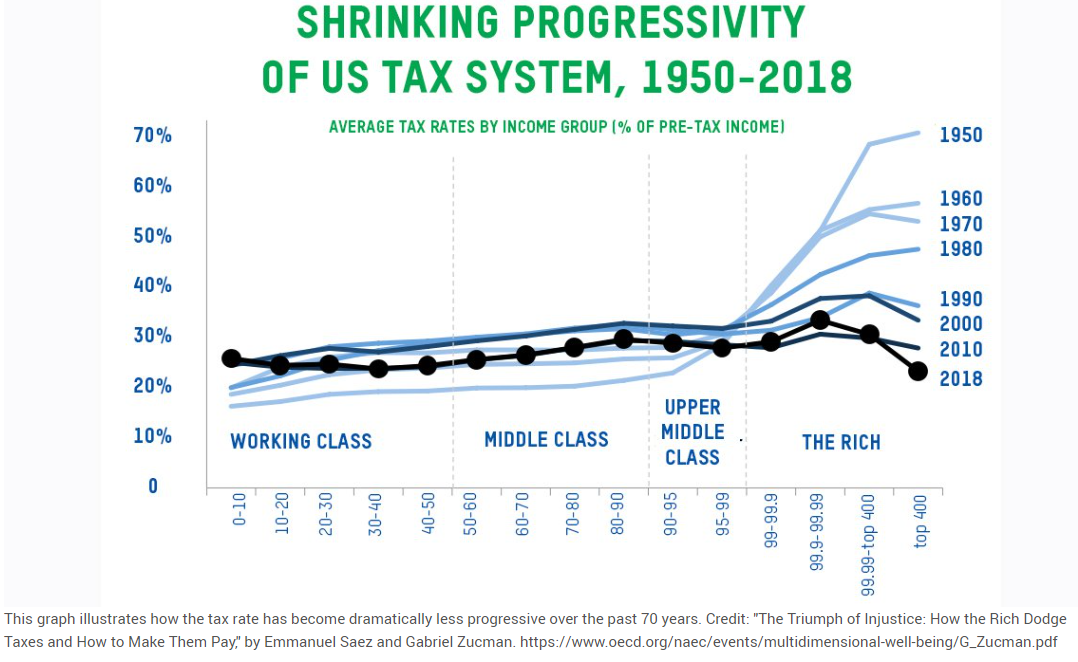

Such a tax attempts to remedy a regressive element of an income tax system regularly argued to be progressive. In the tax context, progressivity means that higher income individuals pay a higher effective tax rate than low income individuals. The argument is that a tax rate of 10% on someone earning $50,000, which results in a payment of $5,000, is far more painful than a tax rate of 10% on a $200,000 income that nets $20,000 of tax income. As income rises proportionately, economists commonly accept that the dearness to earners of that last 10% of income falls.

Hence, the idea has been to increase the tax rate for high income individuals.

The wrinkle is that our economic well-being is tied not so much to our income but also our wealth. One who has no job and earns no interest or dividends on investments, but has a stock portfolio of $10 million has access to a great deal of income, if they wish to tap it.

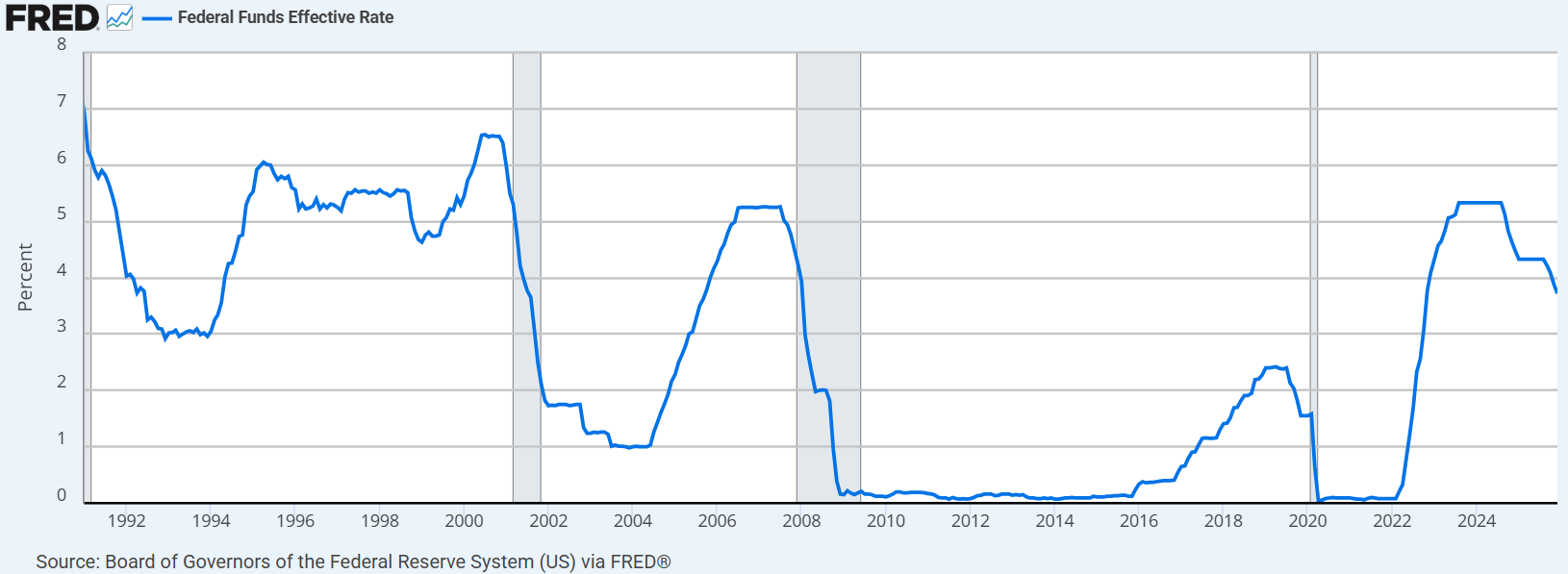

In fact, they can use that wealth to secure loans against it and earn a tidy sum each year. Let’s say that wealth is rising in value at about 8%, which is the average annual increase of the S&P 500 stock index. About 2% of those increases are eroded by inflation. Let’s say a borrower with $10 million invested could use just 6% of their stocks as collateral for a loan each year at a 3% interest rate. They could reap $300,000 in income annually even after paying interest on the loan. And, the value of the portfolio would remain at $10 million. Since loan proceeds are not considered income, they are not taxed. This individual could then live very comfortably and income tax free.

Wealth taxes proposed in Vermont, Washington State, and elsewhere would fill that loophole which exempts from taxation any income that accrues to wealth but is “unrealized” if it is not converted to cash. Of course, a tax on such unrealized capital gains should be rebated should the wealth decline in value, to be fair.

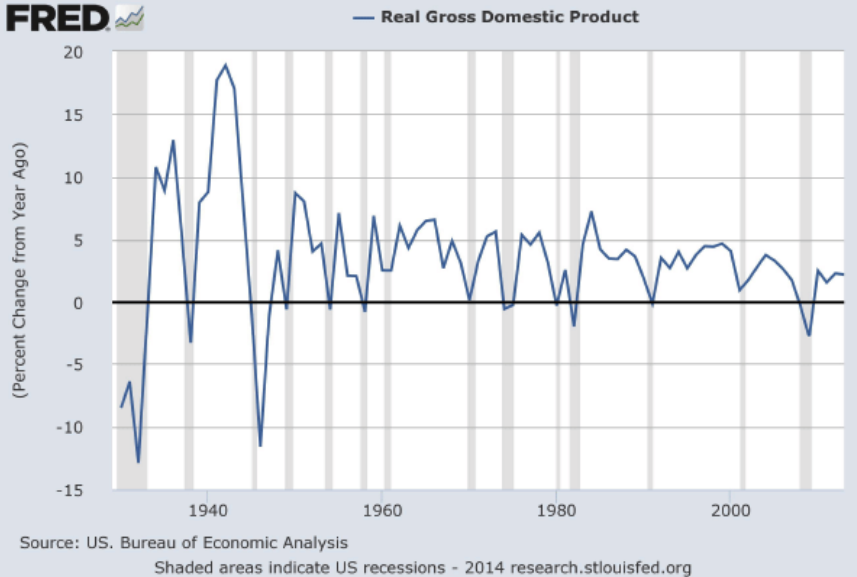

Our nation has been accustomed to sheltered unrealized capital gains for generations, ever since income taxes were first imposed in 1861. That modest Lincoln-era tax was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1894, only to be reimposed by states’ ratification of the 16th Amendment to the Constitution in 1913. Then, the income tax only affected about 1% of the population, and about 1% of their income. My, times have changed.

You might ask how states could levy a tax on wealth but the Federal Government does not. The amendment follows a general principle that any tax on Americans must not unduly discriminate against one particular state. If one state has the same per capita income as others, but has greater wealth, it would pay a larger burden than the others. Hence, wealth taxes are constitutionally barred at the Federal level.

However, local governments are funded primarily through a wealth tax, even though we are so accustomed to it that we long forgot that property taxes are based on housing wealth. In fact, poor senior citizens who are fortunate enough to own their home are often burdened, and many must move away from their families, as their cities continue to up their property tax payments as their neighborhoods become wealthier and their homes hence become more valuable.

Equity in our homes is by far the largest share of wealth for most Americans, and represents about twice the wealth as a typical citizen has saved for retirement. Our home values are taxed in my area at a rate of about 4% of its value each year, regardless of whether we or our bank still owns most of our home. A 4% tax rate on the predominant form of wealth is huge, and exceeds the wealth tax proposed by the State of Vermont. In addition, it is a tax on total wealth, not just the increase in wealth that Vermont proposes.

At a 4% tax rate on total wealth, our cities and school districts in this area essentially requires us to pay to local government the full amount of our home every 25 years. That is a very high tax indeed, and for many residents, especially senior citizens, it represents not only the largest tax they pay each year, but also the largest single item in their budget each year. And, since the value of a home represents a far higher proportion of wealth for lower income households than for the wealthy, the local wealth tax is highly regressive. Even renters, who typically pay a greater share of their income for housing, pay this property tax burden. The tax is hidden in their rent, but it represents a disproportionately high share of their income.

Of course, to tax each year the total wealth, as a property tax does, could be regarded as unfair. Vermont's proposal is only to tax the increase in wealth, or the income generated from wealth, realized or not. From that perspective, Vermont's proposal is far less regressive and onerous than the property tax.

Based on these principles, and on the observation that the 16th Amendment constrains the Federal government but not states, Vermont should not be barred from the tax it proposes to collect, and a form of the tax every one of its local governments collects regularly. However, that does not mean it won’t be challenged, likely all the way to the Supreme Court. A case from Washington State is currently being deliberated, with a ruling expected by the Supreme Court of the United States at the end of their term in June.

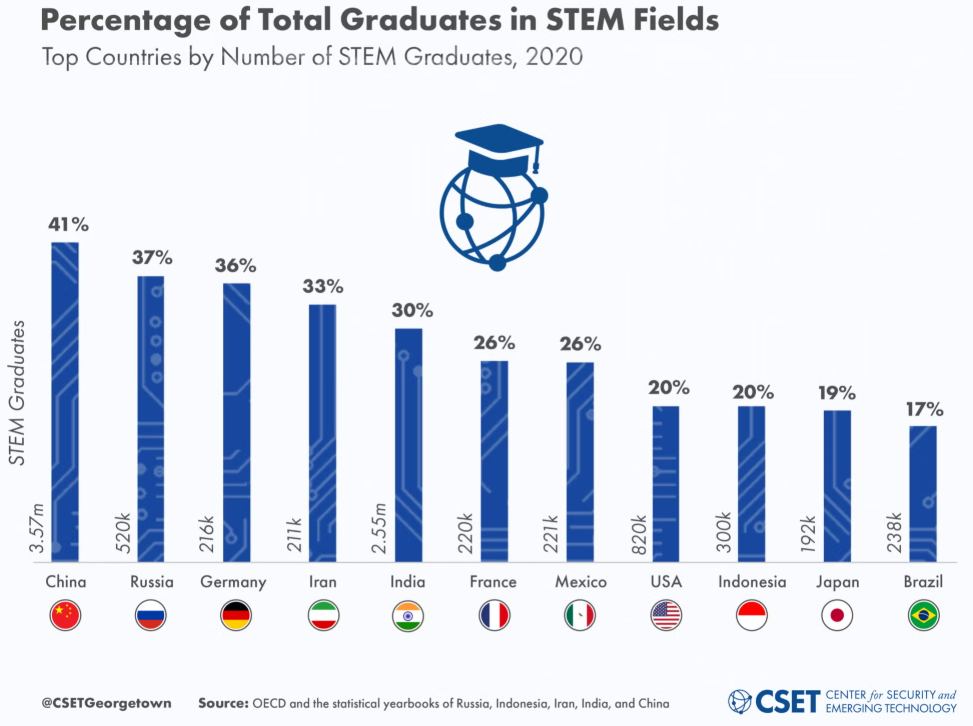

If we believe in income tax progressivity, we may need to discard some of the conventional wisdom about our various forms of income and figure out ways to share the burden of government that are more reflective of a shared capacity to pay rather than a system that by chance or design has tended to favor those most able to shelter wealth. This proposition will become increasingly important as the trend toward manufacturing and service sector job losses over the past few decades have concentrated much more wealth in the owners of technological innovations. This phenomenon of increased wealth concentration will accelerate dramatically with the development of Artificial Intelligence, and its potential, by some estimates, to make almost half of today's jobs obsolete, and which will grow companies such as Google, Apple, NVIDIA, AMD, Meta, Tesla, and Amazon, and the wealth of their owners, to gargantuan proportions.

In a column coming soon, I will describe another proposal in Vermont, an expansion of the Polluter Pays Principle to greenhouse gasses.