Colin Read • September 9, 2023

What Makes an Economy Tick - September 10, 2023

We live in a free market system. Just what does that mean?

To understand how different the last couple of centuries have been compared to the sixty centuries since the beginning of civilization or the three thousand centuries since homo sapiens first walked this Earth, let’s imagine for a moment what came before this most recent flash in the pan.

The word economics comes from the Greek oikos, which means our house, or, more metaphorically, our surroundings. Ecology is the logic of our environment, while economics is its management. Since the beginning of homo sapiens, we as a species have learned to master how we can manage nature for our own benefit, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Humans and domesticated animals kept to sustain humans make up 96% of the mass of all mammals on the planet. Of this human ecosystem, homo sapiens and cows make up about an equal share of about 35% each of the total mammalian biomass. Clearly, humans have learned to dominate the natural ecosystem.

Let’s turn back to the fundamental economic question. If humans are now able to harness our natural and human-made world to satisfy our wants and needs, how do we ensure that this anthroposystem performs well in managing what to produce and who gets to consume? This is the economic question - the coordination of production and consumption.

We’ve discussed in this blog and I’ve described in greater detail elsewhere the problems that have been created when human needs come at the expense of environmental sustainability. Global warming is but one immense natural problem of human creation. Let’s today explore another aspect that is worthy of our reflection.

Over the vast bulk of the centuries of human existence, the fundamental question of who produces and who gets to consume was relatively straightforward. Small clans, typically along family lines, hunted and gathered food. By the very nature of hunting and gathering, these small clans could not have hunted and harvested beyond nature’s capacity. This capacity held human populations in check just as all species attain a symbiotic equilibrium in nature.

This equilibrium remained unchallenged for almost three thousand centuries. By the time of the first cities around five or six thousand years ago, humans had thoroughly transitioned from a hunting and gathering nomadic lifestyle to one in which they domesticated plants and animals and built permanent dwellings. Trade allowed humans to bring in resources from elsewhere, and hence allowed us to exceed the local carrying capacity. The patriarchal and matriarchal power to dictate what was produced and for whom was replaced by political power to allocate the fruits of burgeoning economies.

This system of (mostly) patriarchy and politics prevailed until the Enlightened Age and the Renaissance. Then, in almost the blink of an eye relative to the duration of human existence, there was an emphasis of individuals rather than the collective. A new system of markets replaced politics and the franchises for affluence they granted.

We are all familiar with the functioning of markets ever since. In fact, it would be difficult to imagine anything but what each of us has grown up with, as have our parents and grandparents going back to the time of Adam Smith more than two centuries ago.

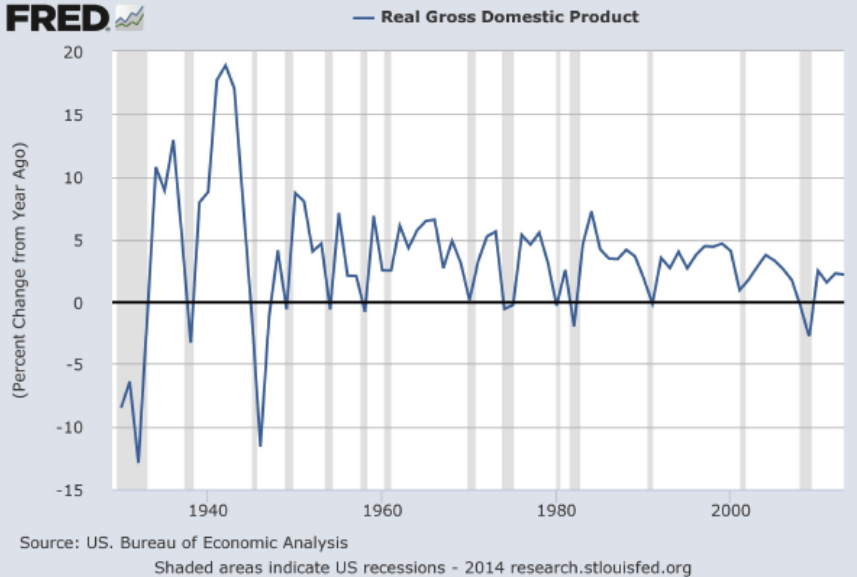

The incentives the free market provides for innovation and the pursuit of profits has created efficiencies unmatched in human civilization. The resulting economic engine has also demonstrated a capacity to easily outstrip the capacity of nature to supply us with the natural resources we need to sustain humans and the planet.

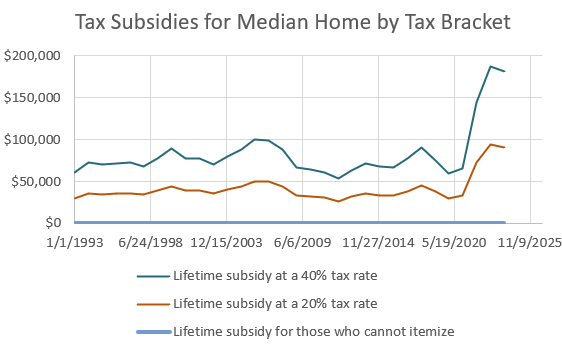

What is so obvious, though, that few of us acknowledge any more is that the free market system acts with incredible efficiency for almost unbridled growth, but it also has a very peculiar allocation mechanism. For the most part gone is the ability of the most physically or politically powerful to skew distribution dramatically in their favor. It has been replaced with income and wealth as the allocation mechanism. Whereas a clan ten thousand years ago may have allocated output based on need, the free market system allocates based on purchasing power. Those with the greatest wealth can divert the most production their way, regardless of their needs.

The discipline of economics was gravely concerned about the need to enhance both the efficiency of production but also the fairness and equity of consumption. This philosophical concern about an economy’s ability to allocate production to those who benefit the most was subsumed by only the smallest change of verbs. The highest benefit was replaced by the highest value, with value most strongly correlated with purchasing power and income.

Of course, we all commonly understand this implication of a free market system that allocates based on income rather than need to the point that this fundamental premise is rarely challenged. Rich and poor alike would similarly conclude that, of course, goods and services go to the highest bidder. Attempts to employ some other sort of allocation mechanism, such as in now-defunct centrally planned communist societies, have invariably produced such inefficiencies that even the poor prefer the harshness of free markets over the capriciousness of centrally planned economies.

I provide this short lesson in the evolution of economies only to ask you to be mindful of your participation in the free market system. Economists recognize some of the weaknesses of market economies and have proposed myriad ways to make them more efficient at generating maximum happiness and less taxing on the environment and each other. Certainly the very method of allocation based on purchasing power and hence income in a free market economy has its proponents, and these advocates are often most associated with the political power that perpetuates our current system.

Fair enough, so long as we have pondered the problems our system creates and are willing to use the tools available to our society to lessen the implications on such artifacts as global warming and resource unsustainability. Almost everything we see around us is touched by the economic system that did not even exist a few centuries ago and has created both great wealth and profound ecosystem damage ever since. Our mindfulness may allow us to defer some of this wealth to heal some of the damage our almost unbridled growth has created.

If we can do so, we may also harness the incredible capacity of a free market system to at the same time make the planet sustainable and more equitable. Certainly the empowerment of the individual reduced the oppression of the politically powerful. If the embracement of consumer sovereignty and the individual can result in such incredible efficiency and empowerment, our mindfulness of this power also has the potential to support other societal and ecosystem values. As with free markets, the choice is up to us. Economics has created some powerful tools. Just like any tool of human creation, we have the capacity to use them wisely and mindfully.