Colin Read • March 10, 2024

What Will He Do Next? - March 10, 2024

The market remains rife with speculation about what Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve will do next. It’s time to throw conventional wisdom out the window.

The term “conventional wisdom” was popularized by the great and looming Canadian economist John Kenneth Galbraith. He meant it as a derision of popular misconceptions, although some believe that such conventional wisdom is sound. Galbraith argued it may be convenient, but it is not good.

Since the Great Depression and through the war years and the prosperity that followed, economists have been comparing price inflation to the unemployment rate. The KIwi economist A.W. Phillips had observed a relationship between unemployment and wages in the U.K. from 1861 to 1957. His conclusion that inflation decreases as unemployment increases has been described as the Phillips Curve ever since. It’s time to put away childish things.

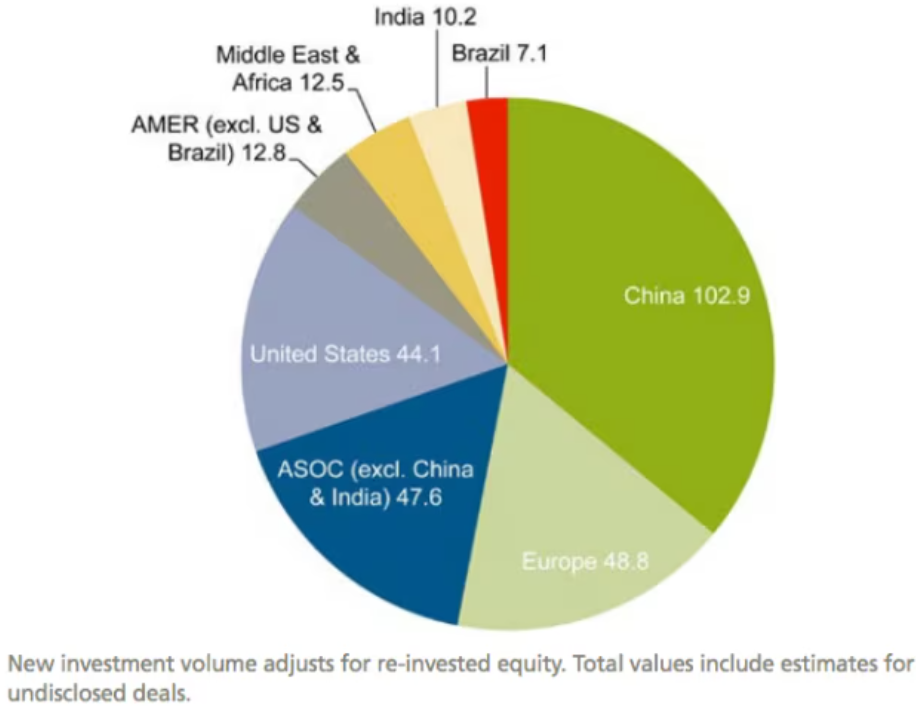

Today’s graph offers our monthly revision of various rates of inflation, including the Fed’s favorite Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI). We see exactly what this blog has been observing for the past two years. When one compares annualized quarterly price data that the Federal Reserve most closely watches, inflation has been coming down steadily for the past two years. This process of inflation moderation began well before the Fed decided to raise interest rates.

We also see that the Federal Funds interest rate the Fed sets had no real observable effect on prices. The very predictable supply shortages that spiked prices following the pandemic began to moderate as people went back to work. This is the anti-Phillips Curve. Higher employment reduced rather than raised prices. The Phillips Curve became inverted.

Unfortunately, the Fed was too wed to conventional wisdom. Well after the price spike, the Fed closed that barn door by jacking up the interest rate they charge to banks who must prop up reserves, and induced a series of spectacular bank failures. We are still experiencing the aftermath today.

This repeal of the Phillips Curve is problematic if it still acts as the basis for monetary policy. We are in a different regime than when Phillips made his observations. His era was low tech, before computers and an activist Fed and well before the Internet. His logic was that when the unemployment rate is high, lack of income and purchasing power tends to moderate prices.

In this modern information era, matching of jobs to workers is extremely efficient, to the point that just about anyone who wants a job can find one in minutes. Gone are the days when one would trudge on down to the employment hall (like when I was a young adult) and see if there are any new job listings. A click of a mouse matches workers to jobs. Since that era, and but for a major pandemic, the unemployment rate in the U.S. has hovered in the three percent range, well below the 5% norm once considered full employment.

The nature of jobs has changed as well. Not only are geographic mismatches solved since the Internet, but we are increasingly a service economy for which many workers can be quickly trained. Gone are the days when laid-off auto workers waited with baited breath for a new assembly line to hire because they were unqualified for a construction job. Now, jobs are more commodified, with easy-to-find retail jobs always awaiting an eager employee.

So, in any conventional era absent a complete remaking of the job market or a once in a century supply disruption from a pandemic, the Fed’s belated policy might have made sense. We should look at the Fed’s policy more in light of interest rates held artificially down for far far far too long following their previous intervention in the wake of the 2008 Great Recession. What the Fed has really done was get us back to a normal real interest rate, defined as the difference in the nominal rate they set and the inflation rate. The effective Fed Rate is now at 5.33%, while various measures of the inflation rate continue to moderate this month below 3%. This yields a real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate in the two percentage point range.

Even at two percent, the real interest rate is low, on a historical basis. The Fed made such a rhetorical statement for high interest rates in the wake of their policy to keep interest rates down far too low for far too long that they are now feeling a lot of heat to bring interest rates down. This pressure is mitigated by the fact that the unemployment rate remains low, the job market still has some tightness and is showing healthy increases in the number of jobs, and the labor market size is declining for this and the next couple of years as we see the largest rate of retirement that this nation has ever experienced. This is the new normal. Situation Normal, All Fluffed Up (SNAFU).

So what will Jerome do next? He feels the need to throw markets a bone. They love low interest rates. Presidential candidate Trump promised not to reappoint Powell in 2026, and low interest rates will improve President Biden’s prospects. If politics played a part in the belated interest rate increase, they may also play one in a token interest rate decrease. There may be one or two minimal and symbolic decreases before the election. That way, the Fed gets markets off its back, tilts the presidential campaign a smidge, and improves its stature in the public’s opinion. The alternative is to hold steady for fear of appearing political. That seems equally likely.

If only it were that simple for the Supreme Court.