Colin Read • September 21, 2024

A Rate Change of Historic Proportion - September 22, 2024

A few weeks ago I predicted that the U.S. Federal Reserve would lower the discount rate by 50 basis points, or half a percentage point. Some were a bit incredulous about that estimation, but let’s dive into why it made sense, then, and on Wednesday when the Fed did just that by making a belated correction rather than a policy redirection.

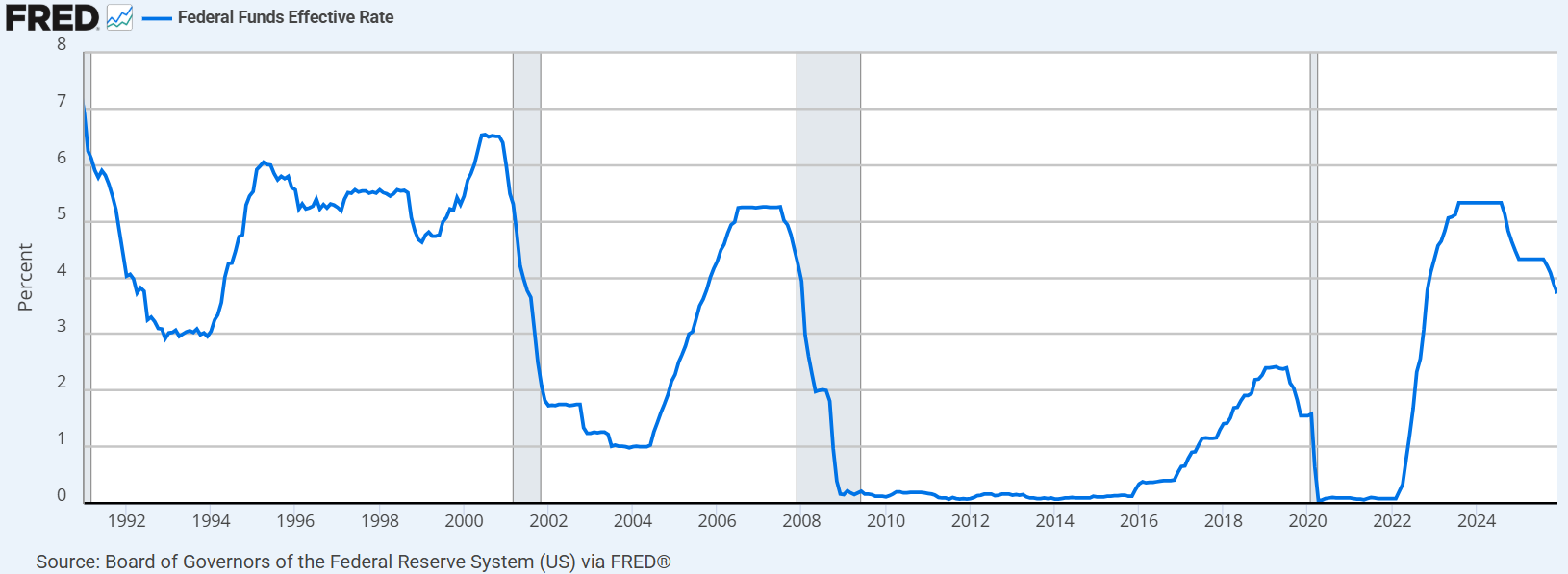

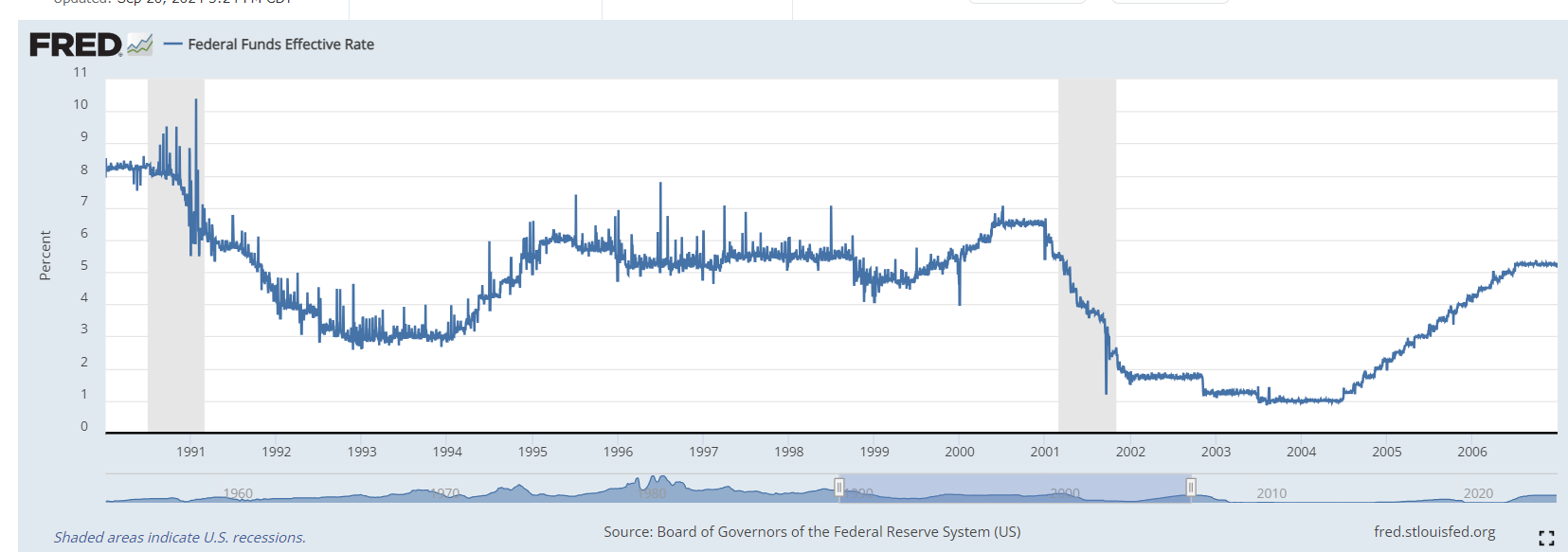

Such a drop in the discount rate of more than a quarter point is exceedingly rare. In modern Fed history, it has only made such a large cut in interest rates three calamitous times. Once was to ward off a looming post-dot.com boom recession in 2001, once to deal with the emerging global financial meltdown in 2007, and once as COVID clamped down on us in 2020.

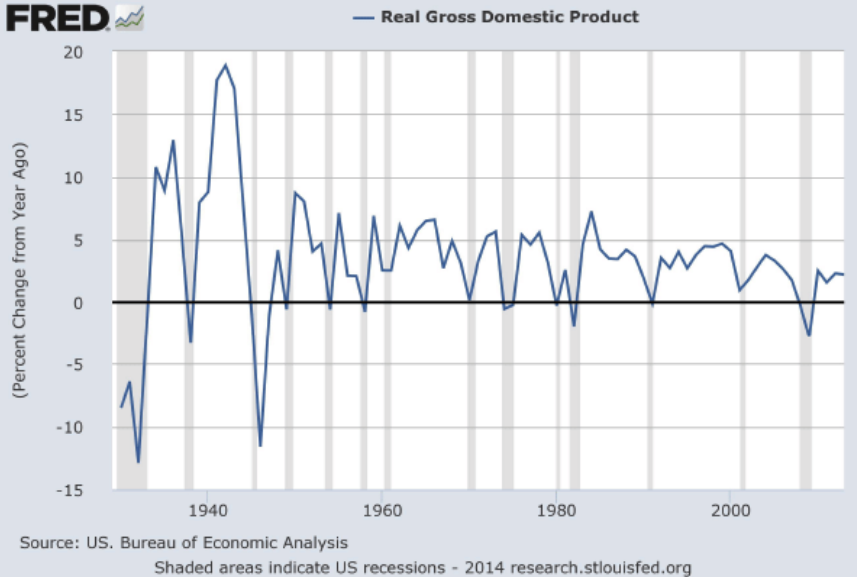

There is no such calamity today, by any measure. The economy has proven relatively resilient of late, readers of this blog realize we took control of inflation not just recently but by early in 2024, and there are no looming storms on the horizon. Surely these times are nothing like the onsets of the Great Recession or COVID. In fact, if we simply look at the data, we would conclude that while the interest rate is historically a tad high, it is not dangerously so.

The U.S. interest rate is not in sync with other nations, though. Canada’s discount rate is 4.25%, Australia’s is 4.35%, and the European Central Bank is holding its interest rate for its commercial bank depository window at 3.5%. Meanwhile, the Fed just dropped its rate to between 4.75% and 5.0%. The Fed rate remains high, both in comparison to the rate of comparable central banks and to the historic average range of around 3.5% over the decade (the crazy years following the Great Recession aside).

The Federal Reserve publicly adopted a policy in the early 1990s to use its power to control inflation while it maintains a healthy rate of employment. Since 1990 and up to the end of 2006, the average discount rate has been 4.35%. We are now barely half a point above that historic range, and the Fed has announced it shall make another couple of cuts, surely at .25% each over the near future, and perhaps by the end of the year, unless an economic calamity besets us.

The best way to look at this is to not read so much into the Fed move. Fed Chair Powell telegraphed to us that this move was more of a normalization than a statement of any great concern. To make such a dramatic move in the absence of any economic drama required an explanation. Of course, political campaigns will try to draw different conclusions, one perhaps that it evidences severe economic malaise, and the other instead focussing on the comments that the economy is basically healthy and has successfully licked inflation.

Let me use an analogy. I imagine many people believe flying an airplane is very difficult. Actually, it is quite easy once the plane is in the air. All airplanes are designed to essentially fly themselves in that inherent stability is designed into them. If one sets the throttle and elevator trim to a specific setting, an airplane will fly just as it is set every time. An airplane may oscillate above and below the expected performance but it will pretty quickly settle down to the set-and-forget phase of flight.

The economy responds in the same way. Barring some sort of psychological malaise among consumers or problems with supply chains that may arise from a rare event like COVID, an appropriate interest rate will keep the economy in the goldilocks range that is not too hot and not too cold.

That rate, as evidenced by Canada’s and Australia’s central banks and the Fed’s discount rate history is about 4.25%.

So, why did the Fed not just normalize its rate by a full percentage point immediately rather than wait for a couple more drops? Unfortunately, markets would read into such an unprecedentedly large move as a message that the sky is falling rather than as a natural response to perhaps a bit-too-cautious reluctance to lower the rate.

It is this reluctance to lower the rate until inflation was definitely in the desired range forced the Fed’s hand. As readers know, inflation based on quarterly data has been in the proper range for more than half a year, but markets, and hence the Fed, paid too much attention to annual rather than annualized quarterly inflation. But, once even the annual inflation rate that included data from a year ago came into line, a significant correction was necessary and appropriate, albeit a bit late.

With the rate drop and the stated expectation of further and more modest drops, the economic trim has been properly set. The Fed is riding the economic airplane to its desired level of performance with a bit too heavy hand on the yoke perhaps, but to simply set-and-forget would have alarmed markets and produced a pilot-induced dive.

As stated earlier, this move will be politicized. I’ve been critical in the past of Powell, a trained political scientist rather than economist, as being politically too clever by a half as he awaited raising interest rates to battle COVID supply chain-induced inflation until after he was reappointed Fed Chair in late 2021. Whether or not there was indeed any link between the reappointment and delayed response to inflation, the Fed did not want to be criticized as playing politics by delaying imposition of the appropriate policy this week.

This is the fine line the world’s most watched economic authority must walk. World markets hang too literally on its words and deeds, something that once-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan discovered when reference to “irrational exuberance” in a speech to a group in Japan in 1996 resulted in a market nosedive. It is not only the words expressed that are important, but how they are filtered and perceived by the greater public and how they feed into any artificial narrative that cynical or self-serving politicians may develop during an election year.

Maybe that is why Powell’s political instincts are relevant. He understands better than most that to just set-and-forget with its policies is simplistic, just as to keep too firm a hand on the controls is equally imprudent.

Of course, after a decade of almost zero discount rates has been seared into our brains and expectations. It will take a while, and a fair amount of consistent narrative, for the Fed to wean us off of artificially low interest rates. The Fed’s words and deeds are appropriate, if a bit unnerving for some. Personally, I like my coffee black