Colin Read • September 15, 2024

Too Easy To Criticize - September 15, 2024

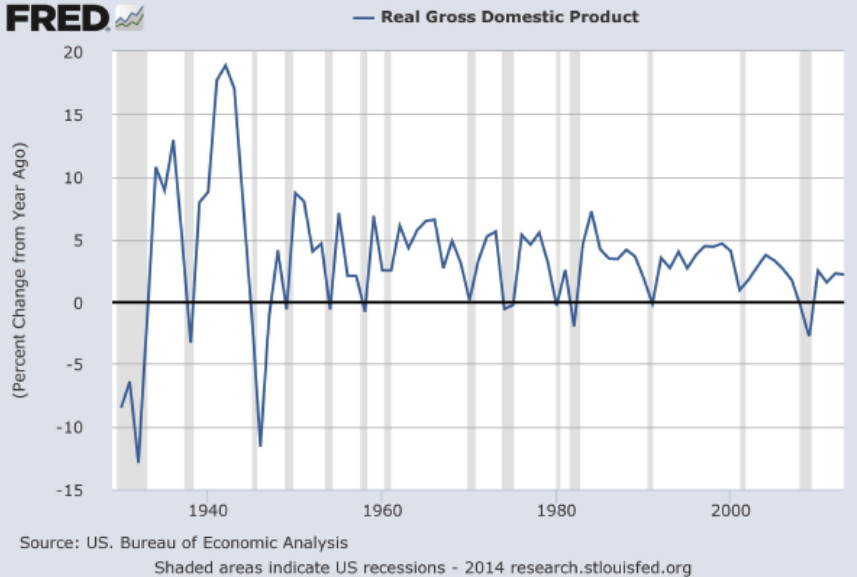

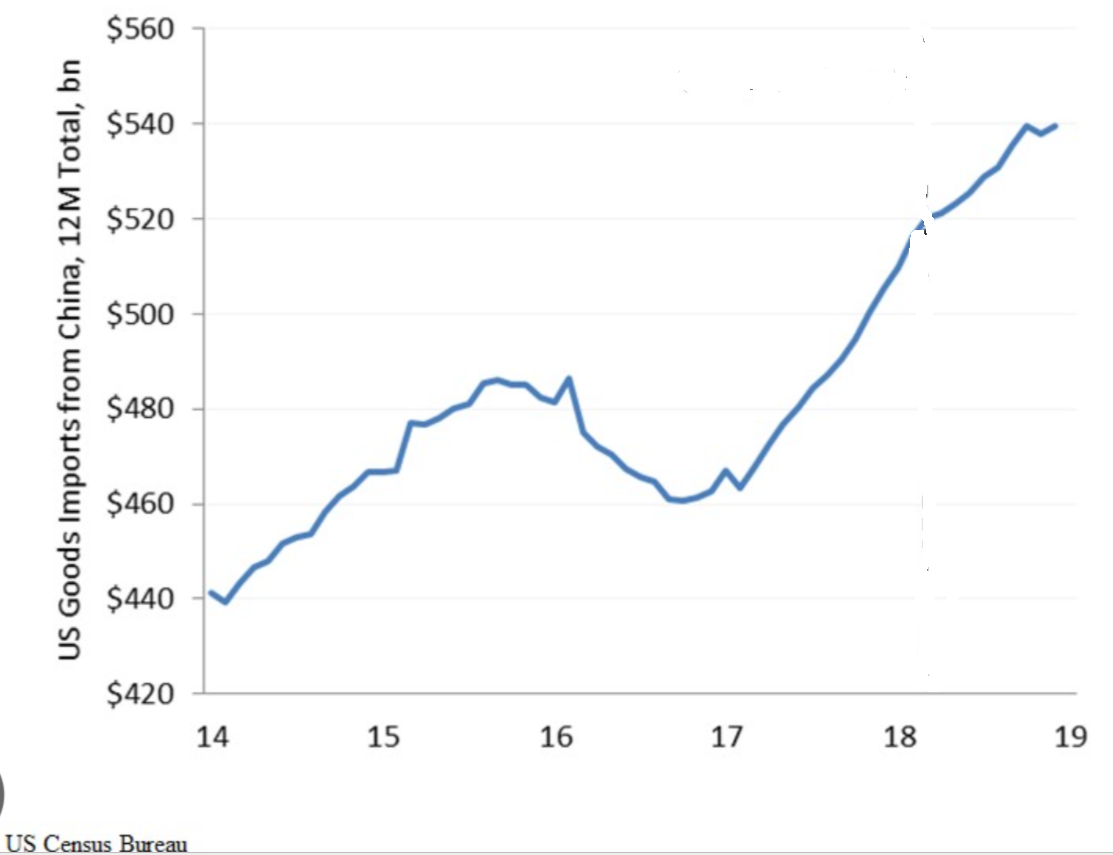

Last week I described why economists might be skeptical of the policy proposals of both major presidential candidates. One candidate proposed broad and deep import tariffs that would immediately raise the price significantly for most items at Walmart, while it will also disadvantage our exporters who rely on intermediate factors from elsewhere. In the end, inflation would ratchet up significantly, jobs will be lost, and domestic producers will have greater latitude to raise their prices and price-gouge, and the penalties on exporters will worsen both the trade deficit and the value of the dollar. Today’s graph showed that antitrade measures imposed following the 2016 election increased rather than reduced the cost of imports to American consumers. .

Meanwhile, the other candidate proposes to solve the problem of dramatically frustrated housing supply by increasing housing demand through a $25,000 grant to new homebuyers. Current homeowners will benefit from the resulting higher prices as demand outstrips fixed supply, but the policy won’t help the new homeowners the policy promises to promote.

It’s too easy to sit on the sidelines and say what won’t work. But, what will?

First, for those parents out there, please recall what it was like with a two year old. One o the first words they master is NO. There are not two letters in combination in the English language that have so much power. YES is affirming, collaborative, and carries with it some responsibility to be part of the solution. On the other hand, NO is negating and carries with it no responsibility to help solve the problem. In fact, the intransigence of NO usually makes the problem worse and the solution more elusive.

I preface my recommendations with the acknowledgement that many people will say no to what I describe. They are probably not negating the policies because they feel the common good will be harmed or, in the parlance of economics, the economic pie will be reduced in size.

Rather, objections usually come from perceived harm that lessens one's share of the pie, even if we recognize others benefit more than what one might lose. If indeed the gains exceed the losses, surely we could use some of the gains to indemnify those who lose. Unfortunately, such compensation is rare in reality.

Instead, I wish there was such a thing as an economic Mulligan or two. Can we do things that once in a while cause some to suffer a bit, but benefit far more a lot, and ask to be excused for the economic travesty? Using a concept we often discuss in this blog, could people permit a NIMBY (not in my backyard) once in a while instead of grinding economic problem solving to a halt?

With that out of the way, let us offer a couple of solutions that would actually solve the problems we described above.

Instead of imposing tariffs that will invariably boomerang back and hit us in the back of our head, we should increase the competitiveness of domestic innovators in a number of ways. First, we should ensure that patent protections are a bit more realistic. There is far too much gamesmanship in patent protection that benefits lawyers but does little to spur innovation. A decreased period of protection and a greater emphasis on mediation or arbitration of disputes might add more certainty to the innovation process and curtail the monopolies excessively aggressive patent protection affords. Some very deep pockets might not like such a reform, but it would not much hurt the little guy innovator who is run over by the patent process anyway.

Let us also make it far easier for our companies to attract workers. Too often workers must juggle daycare and healthcare coverage, both of which employers find difficult or expensive to offer. The same goes for energy. Hydroelectric dams use our natural water resources, wind and solar need land (but doesn’t care if it is land of great utility or not), and our regional grids must move this power around. We should view energy as a collective good from which we all benefit and for which we should all encourage and direct to projects most able to generate jobs (no pun intended), advance science, and make us more productive. In other words, energy is a compelling national interest upon which our global competitiveness (and sustainability) depends.

We should recognize that such a national interest should prevail in the face of NIMBY opposition. People may not want to witness a wind or solar farm, but we all happily use the energy they produce and the jobs they create.

The same Mulligan principle that could prevent efforts to thwart the expansion of sustainable energy access, daycare for working families, and inexpensive access to healthcare can also be used to expand the supply of housing.

Homebuilding is expensive in part because land is considered private property to a most significant degree. Henry George, the great 19th Century economic commentator, and many others going back to Adam Smith and David Ricardo, lamented that land speculation frustrates the enjoyment from productively using the land most effectively. We can reduce land speculation and promote new construction by more heavily taxing the value of land, or by holding some land in public trusts that is then leased for 99 years to build homes. That way, a young family can purchase a home for little more than the cost of home construction rather than land speculation. In combination with the declaration of homeownership as a national interest and the coordination of building codes and zoning according to uniform national standards, we can convert the housing industry from one of speculation to one of housing consumption. Prices would fall dramatically, and the savings of young people that would have otherwise been consumed in mortgage payments could instead be used to invest in their retirement.

Now, I know that many readers are by now muttering “that won’t work” because we all realize how radical such a redefinition of some prized land as public property may be for our societies that prize private property. Such invocation of a national interest in these important sectors of research and development, sustainable energy, and housing is far too much for the U.S. and maybe a little too much for Canada to swallow, but is practiced without much objection in China. That is why they can design and build in a couple of years a 500 mile High Voltage Direct Current distribution line while it takes twenty years to approve and construct here. And, they can build high rises at the rate of a floor a day and go from concept to occupancy in a year, and state as a matter of public policy that more sustainable energy will be built, and more factories devoted to windmills, solar panels, and the electric cars upon which the U.S. opts to impose tariffs.

One might argue that China's economy is not as developed or competitive, their infrastructure is unsafe and flawed, and their products and innovation are not world class. Just the briefest of visits to China will demonstrate our misconceptions and biases are untrue and hold us back far more than it does them. Certainly they have a political system that lacks the luxury of democracy, and they have a culture that emphasizes cooperation and tolerates imitation far more than we do here. Property rights are viewed more collectively than individually in a land the size of U.S. or Canada but with more than three times the U.S. population and thirty times that of Canada. I don’t imagine the NIMBY movement is very strong there.

We need to discover a pathway from a NO society to one in which we take responsibility to build a better economy. That is far more work than just saying no, I know. But, with such pressing issues as the production of clean energy and the affordability of housing upon which our children and grandchildren shall depend, we need to turn NO into YES, BUT.

Of course, we should applaud NIMBY to prevent dirty industries or freeways from destroying poor communities because the disadvantaged don’t have the luxury of a backyard or the time to petition local government. But it would be great if in some really big ways we could think as a nation rather than as a collection of spirited and self-interested individuals. We should move away from a speculation economy and into the production economy that creates sustainable growth rather than merely recuts the economic pie. It requires us to be a nation of makers rather than takers.

I guess you see now why I am no longer involved in politics, ‘cause that is crazy talk in the great American debate!