Colin Read • August 13, 2023

Core Inflation is Coming Down Too - August 13, 2023

Most commentators seem to agree that the Federal Reserve has only one or perhaps a couple of small rate hikes ahead of it. With inflation coming down to the very low three percent range, and with the Fed discount rate now at only slightly elevated levels compared to long run averages, there are only a couple of data points that cause the Fed to waffle.

The Fed is most concerned about a translation of tight labor markets and accelerating wage demands on what economists call wage-push inflation. However, labor markets are beginning to cool, the unemployment rate has held remarkably steady and in a range one would expect given the incredible efficiency of Internet-based job matching these days, and with employers making other not-costly concessions such as workplace flexibility as a way to attract workers willing to forego higher wages for greater autonomy.

This leaves one peg upon which the Fed tries to hang its interest rate raising hat upon.

The Fed argues that, while the non-seasonally adjusted “headline” inflation rate has once again come in in the low threes, as we had predicted in this blog it would, they are still concerned about another measure called “core inflation.” This measure describes rising prices in all sectors except the more volatile food and energy components. These sectors are related in that, while food production was once labor intensive, now it is energy intensive, in the diesel that fuels farm machinery and the components of fertilizers that now substitute for soil to keep lettuce on our tables and corn-based ethanol in our tanks.

By removing the whiplash effect of these markets so dependent on spot commodity prices, the Fed argues that they are focussing on a more realistic and reliable indicator of economic overheating. I’m not fully on board.

First, the psychology that drives our demand for higher wages are the price of food at the grocery store, the price to fill up our tanks, and the rent or mortgage payments we pay. It is this inflation psyche that the Fed is attempting to reset when its tight monetary policy slows down the economy. But, if we households respond to food and energy prices, and the Fed ignores them, they are missing the boat.

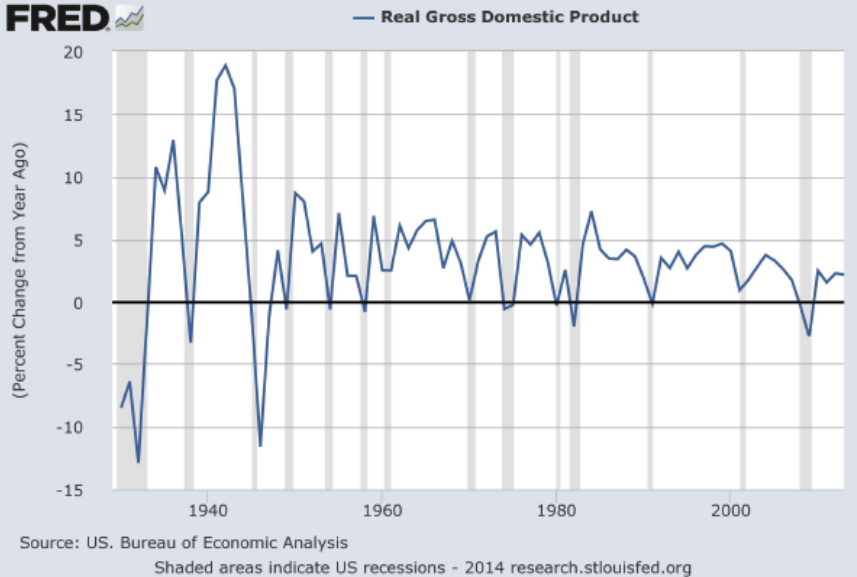

Second, in this blog I’ve harped for the last year on the folly of emphasizing price changes over the past twelve months. The Fed is trying to predict the future by looking way too far back. We have been documenting here how prices from month to month or quarter to quarter have come down dramatically starting almost a year ago. By comparing year-over-year (YOY) prices, a huge price increase such as what we saw last summer has only now fallen off our charts.

I’ve here demonstrated why the headline inflation rate would drop to 3.1% a month ago and 3.2% this last reading. It is because inflation has been in that range for the last three quarters.

We can make that same argument with core inflation that omits food and energy costs. It spiked a year ago but has been in the low 5% range and below on a quarterly basis since late last fall. I predict it will be in the two percent range by next month and will pull down the annual rate to the three percent range by October.

These estimates have little to do with what the Fed is doing now. They are, just as before, simple math and a realization that YOY inflation, be it core or otherwise, places too much of an emphasis on ancient economic history.

With a less tight labor market and now with all inflation measures coming down, the Fed is grasping at fewer and fewer straws to argue for higher yet interest rates. For these various reasons, I believe they will soon relent and let the economy equilibrate, perhaps even without a recession. We shall see. Meanwhile, I await their call! (Not).