Colin Read • August 6, 2023

Not Just the Warmest Month - August 6, 2023

Sir John Franklin wishes he was around today. Actually, he wished he could be around for a little longer not long after his ill-fated 1845 attempt to cross from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean via the Arctic’s Northwest Passage. His doomed expedition was frozen in ice in Victoria Strait near King William Island in Northern Canada. All 145 crew eventually perished as they floundered in the ice.

Roald Amundsen eventually traversed the Northwest Passage in 1906 after a three year struggle. Now, adventurous pleasure craft can navigate the entire passage completely ice-free, and some routes of the Northwest Passage are already ice-free, with the summer only halfway through. By mid century, or sooner, it is expected that there will be ice-free paths all the way to the North Pole.

What a difference a century and a half makes. In Franklin’s day, the mean global temperature held at 13.5 degrees Celsius up to about 1875. At that point, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil produced an innovation that displaced whale oil and wax as a source of heat and light with refined oil. To extend the market still further in the late 1800s, and spur the growth of the Gilded Age, Standard Oil even found a way to use the most volatile components of oil through the production of gasoline. Transportation induced a revolution. The climate has been reeling ever since.

In flying, it is important to determine the performance of an aircraft based on current conditions relative to standard conditions. In the earliest days of aviation, this global average temperature was considered 56 degrees. When I learned to fly, admittedly almost half a century ago, the standard temperature globally, averaged throughout the year, had been 58 degrees Fahrenheit. Since July 3, the average global temperature has been 63 degrees.

The 1979-2000 average global temperature rose to 58 degrees. This year it shall be 2 degrees warmer yet. That is a global average temperature increase of 4 degrees Fahrenheit in a century in a half. We have broached the maximum increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) that presidents and prime ministers worldwide had pledged to not exceed. If this year becomes the norm rather than the exception, we may also blow through the 2 degree Celsius limit that avoids unleashing the worst processes of global temperature acceleration.

This string of record-breaking temperatures may not seem like much. However, global temperature records are rarely set - until recently. The last time the global average record was broken was in the incredibly hot year of 2016, and only on a single day. This year every single day since July 3 has been hotter than any other day in recorded history.

The stream of records broken, not in one day but days, weeks, and now into its second month explains what we are all seeing around us. There is now little doubt that 2023 will go on record as the hottest ever, in a string of accelerating hottest ever years.

This trend does not bode well for the pledges of politicians to hold temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius since the 1850-1880 era, or 1 degree since the mean temperature of the last two decades of the 20th century. In these most recent couple of decades in the new millennium, we have already increased temperatures by about twice the increase of the rest of the post-petroleum period.

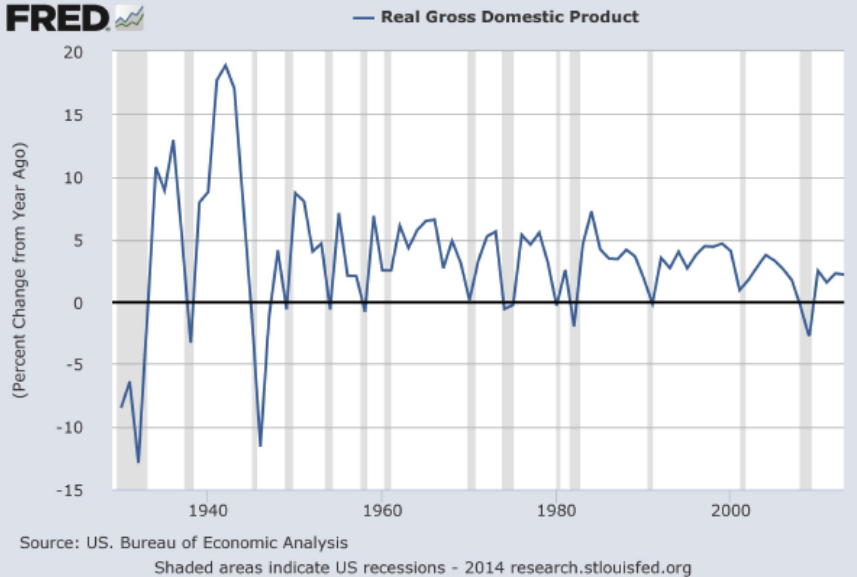

If you conclude things are getting worse very fast, let’s take a closer look at the graph. Notice that the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere are hotter than summer in the south by about 3.5 degrees Celsius traditionally, and more like 4 degrees Celsius now. What gives?

The reason is that there is less land mass in the Southern Hemisphere. Land warms up and cools down much more substantially from solar energy impinging upon us. So where does all that energy go south of the equator?

That is actually the big problem. There is more ocean south of us, and oceans do not warm quickly. Instead, they quietly absorb higher temperatures, and don’t reradiate that heat into space as quickly. They just quietly get warmer, and warmer, and warmer. In fact, while oceans cover 70% of the Earth's mass, they absorb 90% of the sun's energy. That's where everything is happening right now, despite our preoccupation with heat waves on land.

Even by 2020, the average ocean temperature since the prepetroleum era had increased by 1.75 degrees Celsius. Ocean temperatures have risen even more dramatically since 2020 and now exceed two degrees. The upshot is more moisture that evaporates into the air, which changes weather patterns, severe rain events, and the strength and frequency of hurricanes. The oceans are becoming supercharged, and this trend too is accelerating.

One could argue that a day or a month does not make a trend. But, the graphs nonetheless show a dramatic upward trend, with records set regularly rather than occasionally, and this record of temperatures every day over the past month breaking every record before it.

It appears that politicians prefer to wait and see rather than incentivize changes in behavior. Scientific and technological advances are at least assisting in slowing down the acceleration of global warming, but cannot in themselves reverse or even freeze these trends. The world is still burning more coal every year, but not as quickly as before, as most new energy demand is relying on sustainable energy sources.

Each of us can do something to assist in prevention of global peril, but none of us can do much. Unless the public and private sectors improve the grid, permit the solar and wind power installations, and discourage reliance on fossil fuels, we will continue to move one step forward but two steps back.