Colin Read • July 30, 2023

What’s Next? - July 30, 2023

There were no surprises on the economic front this week. We have been predicting for months that the inflation index will come in at three percent this month. I expect next month’s inflation will come in just a bit higher, but still in the low threes when the July data comes in on August 10. This is in spite of food prices normalizing a bit and energy costs stabilizing. Then, over the balance of the year, inflation will bounce around in a narrow range toward 2.8%.

This stabilization of inflation, from nine percent a year ago to six percent six months ago and three percent now is simply 2022 price shocks finally falling out of the twelve month inflation index. Since prices began moderating a year ago, inflation reported today is simply an artifact of the imprecise way inflation is reported rather than great success in either Federal Reserve policy or Bidenomics. Sorry, politicians, but it’s just grade school algebra rather than sophisticated policy.

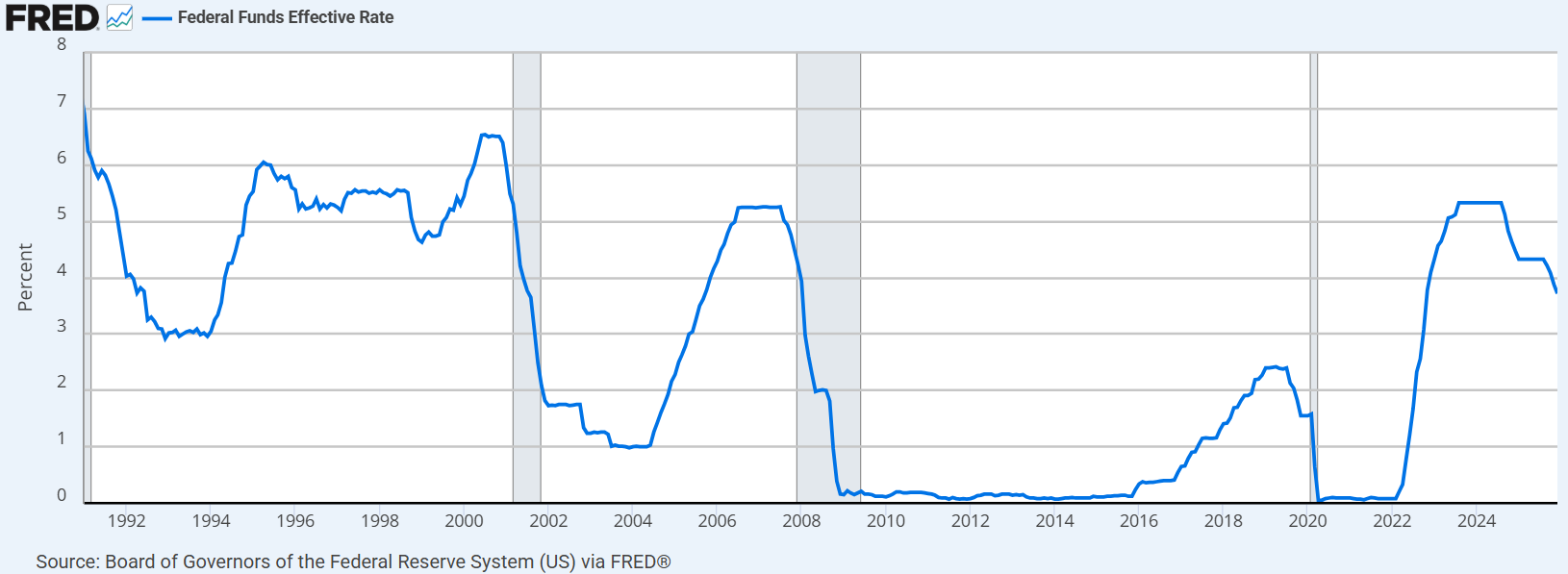

So, what is the Fed accomplishing with a historically almost unprecedented ratcheting up of interest rates?

Let’s take the harsh medicine first. These high interest rates that have pushed home mortgage rates toward seven percent, up from the twos just a few years ago, has resulted in a cooling off of home purchases and prices.

Banks make money by borrowing short term from depositors and the Fed and lending long term for mortgages, commercial loans, and other forms of investment. Bank failures resulted because, over an entire decade of artificially low interest rates and inflation, they had lended feverishly, but at locked-in interest rates around four to five percent. So long as they were paying less than two percent (and often zero) for deposits or Fed funds, banks were able to maintain a margin of around three percent (or more) between their lending and borrowing rates. That margin is what fuelled a decade of bank profits.

So long as inflation and interest rates change only slowly, banks have time to adjust their portfolios to maintain their margins. Loans at rates relevant five or ten years earlier are replaced with loans that more closely represent recent interest rates. But, when their cost of borrowing rises to five percentage points as a result of a rapid ratcheting up of the Federal Reserve rate, their cost of borrowing can exceed the return on their loan portfolio. This has resulted in some spectacular bank failures, including the two largest bankruptcies in U.S. banking history.

Banks continue to fail with Heartland Tri-State Bank going down on Friday. Even though the Fed has indicated that its interest rate increase on Wednesday may not be followed by rates at every monthly Fed meeting for the balance of the year, the banking industry remains precarious. Most banks will manage just fine, but those who flew too close to the Sun with overly aggressive lending may find it difficult to hold things together.

If the Fed’s policy created some downside risk for the economy, what is it designed to accomplish, especially since it started fighting inflation well after inflation began to abate?

The Fed’s biggest fear is that inflation will persist. There is nothing that the Fed could do about supply chain blockages throughout the COVID era, nor the energy crisis in Europe following the invasion of Ukraine. These two supply shocks are since reversed, which is why inflation has come down.

Instead, the Fed is worried about institutionalized inflation. Should workers demand higher wages to indemnify ourselves from higher prices, the private sector will be forced to yet again raise prices because wages represent about 60% of all costs in the U.S. economy.

The Fed is also trying to manage the hangover from half a decade of excessive government spending, through COVID income compensation under Presidents Trump and Biden, and through Biden’s social policies. These policies bolstered consumer bank accounts and increased demand at times when supply was constrained.

These extraordinary balances held in households’ bank accounts have now dwindled, and consumer credit is increasing quickly. Deposits are falling, which also threaten some banks. Consumer spending is expected to decline into the fall. So will investment in new homes and buildings, and industrial expansion as the recently buoyant consumer becomes a bit more concerned about dwindling balances and higher interest rates.

This is what the Fed is trying to accomplish. If it can create some fear of the economic gods in all of us, we may feel this is not the time to spend and certainly not the time to rush into our boss’s offices and demand a raise. The Fed is working on our consumer and employee psychology to be sure prices don’t rise any further.

The question has always been whether it can navigate this tightrope walk without a recession. Actually, if we rely on the conventional measure of two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth, we already suffered a short recession in 2022. Since then, growth has been consistent, if not spectacular. If the Fed can continue to instill concern among us all, but not induce so much fear that we begin to horde our income, we may actually avoid a second recession.

I believe that is possible. The Fed has sent out clear messages that it is going to moderate prices by maintaining its high interest rate policy and discouraging borrowing. But, it will do so at a slow rate from here on in.

Throughout this ramp-up in interest rates, labor markets have remained strong. Only recently have we seen a moderation of job growth as we rebuild following COVID. Our unemployment rate has remained very low, but we should take that with a grain of salt. Unemployment measures those who consider themselves jobless in the numerator to the entire labor force in the denominator. When people pull out of the conventional economy, as we saw since COVID, and we baby boomers begin to retire, both the numerator and denominator decrease, but the numerator decreases proportionally faster. Hence the unemployment rate appears to decrease.

This artifact of demographics is viewed by the Fed as a tight labor market that could demand higher wages. But, it can also represent one more step toward a labor-reduced economy in which people earn income in other ways than competing with AI and automation for jobs.

In addition, the Fed also looks at "core inflation" with more volatile food and energy components removed. This rate still remains a percent or two higher than the recent lower inflation rates as food prices normalize. I will treat core inflation in more detail in future blogs.

For these reasons, I think the Fed will continue to occasionally pump the economic brakes as long as the labor market remains tight.

Let’s assume that this low unemployment rate is the new normal. Then, when we see the inflation rate in the twos and the Federal Reserve rate in the fours and fives, and with GDP growth remaining in the twos, we should observe that this is quite normal. We have forgotten these ranges because of a decade of distorted data. But, actually, the economy may now be in a sweet spot.

The cost of our dependence on a decade of artificially low interest rates is that government debt has absolutely ballooned. It is now about four times higher than in the 2000s. Unfortunately, while when you and I see high interest rates, we reduce spending, governments do not seem disciplined by high interest rates. They can simply crank up the tax rate to accommodate.

We will suffer this debt and low interest rate hangover for some time. The Fed knows that the worst it can do is to allow us to take a hair of the dog shot. It will continue its discipline, and may well keep interest rates in this historical, but new to us, range for some time. That way, if some severe downturn occurs in the future, the Fed actually has an interest rate it can reduce to ward off severe recessions.

We must acknowledge that the Great Recession of 2008, poor economic policy ever since, and COVID have done almost generational damage, and then we must forget about all that, except the part that might cause us to repeat our responses in the future. Sound economic policy, and investments to reduce future costs of climate change should be the order of the day. However, that takes forward-looking vision rather than economic navigation by looking in the rear view mirror.