Colin Read • February 4, 2023

Debt is Good, to a Point - February 5, 2023

In college I tried making yogurt for a while. I thought, wouldn’t it be nice to have fresh yogurt every day, and flavored just how I might like it. For a moment I wondered if it would also be helpful to keep a cow in my dorm room. That way, I could have fresh yogurt and cream for my coffee as well. No reason to stop there, though. If one cow in my dorm room was good, maybe two would be even better.

Well, common sense prevailed. But it demonstrates the notion of diminishing marginal returns. More and more of something doesn’t make it more and more better. Eventually, the additional value of anything tapers off as we have more of it. At some point, something good can even become bad when used in excess. Fifteen minutes of the sun’s rays at high noon gives you a dose of Vitamin D. Four hours gives you sunburn.

Developed nations are able to make the investments we need in infrastructure, programs, innovations, and even our human capital because we have markets for debt and savings. Without well-functioning capital markets, an economy can only live in the moment. And, without the rule of law that protects rights to own the property one purchases, there is little point to invest in items of long term value because ownership is not ensured.

Some debt is then ideal. It is made to balance the amount obliged today to the amount that can be enjoyed on an accruing basis in the future. A student loan is a classical example. By investing in one’s human capital, a lifetime of earnings is enhanced. In addition, society is also more productive, with a greater level of happiness and lower rates of crime.

These are all good things, to the point that student loans and education are subsidized. Society knows that such a personal investment pays dividends for it too, and hence should be encouraged.

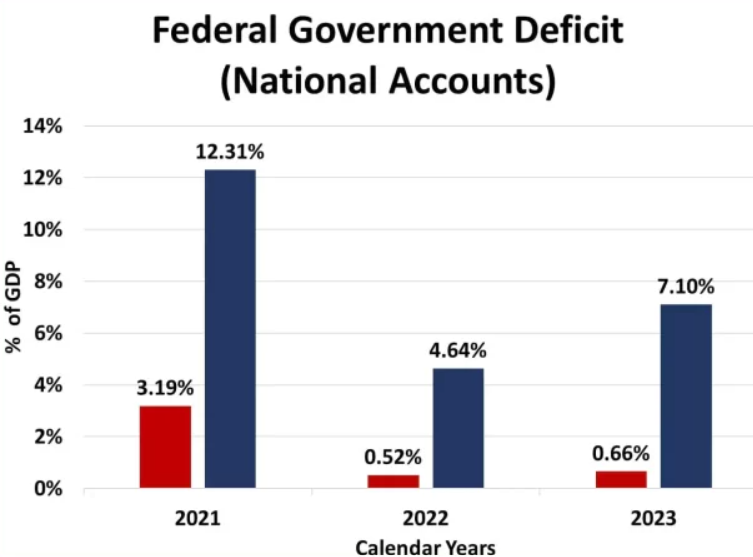

But, what is too much? Just as our nation has about quadrupled the level of government debt in the past decade and a half of incredibly low interest rates that never tapered down following the Great Recession, our households have done the same. We now have more debt than ever before.

And yet, we don’t really have cars that last longer, better education, a higher level of homeownership, or superior credit card purchases that pay dividends to us far into the future. We just seem to have more debt, and, ironically enough, fewer people going to college and a lower level of homeownership.

Instead, just like the government, it appears we have simply gone on a spending spree, consistent with the misguided economic stimulus that served a purpose for a very short while after the Great Recession in 2008, but never tapered back to normal. This terrible practice of both the Federal Reserve in maintaining interest rates far too low and far too long and two presidencies that could not pump more money into consumer consumption fast enough, we are left paying the price.

Over this era, the mantra was “well, money is so cheap that we cannot afford not to borrow at these low rates.” I guess nobody thought that borrowing then usually requires drawing down those balances over time. Maybe people imagined that we can always refinance at low interest rates forever. Well, the chicken (or the cow) has come home to roost.

The United States is experiencing some of its lowest unemployment rates and highest inflation in half a century. Meanwhile, our national and personal debt has never been higher. If there has ever been a time to pump our brakes on spending, to lower inflation, to cool off labor markets that are too hot to sustain themselves, and to start lowering debt by living within our public and private sector means, this is it.

There seems to be little sign of that though. The graph of the day shows a pretty dramatic and historic increase in the level of all forms of private sector debt, except perhaps home equity borrowing. The most recent credit card debt data from this week shows the average balance at almost $6,000, with a rise in total credit card debt since a year ago of 18.5%. Credit card balances will likely hit the trillion dollar mark sometime this year unless reality sets in.

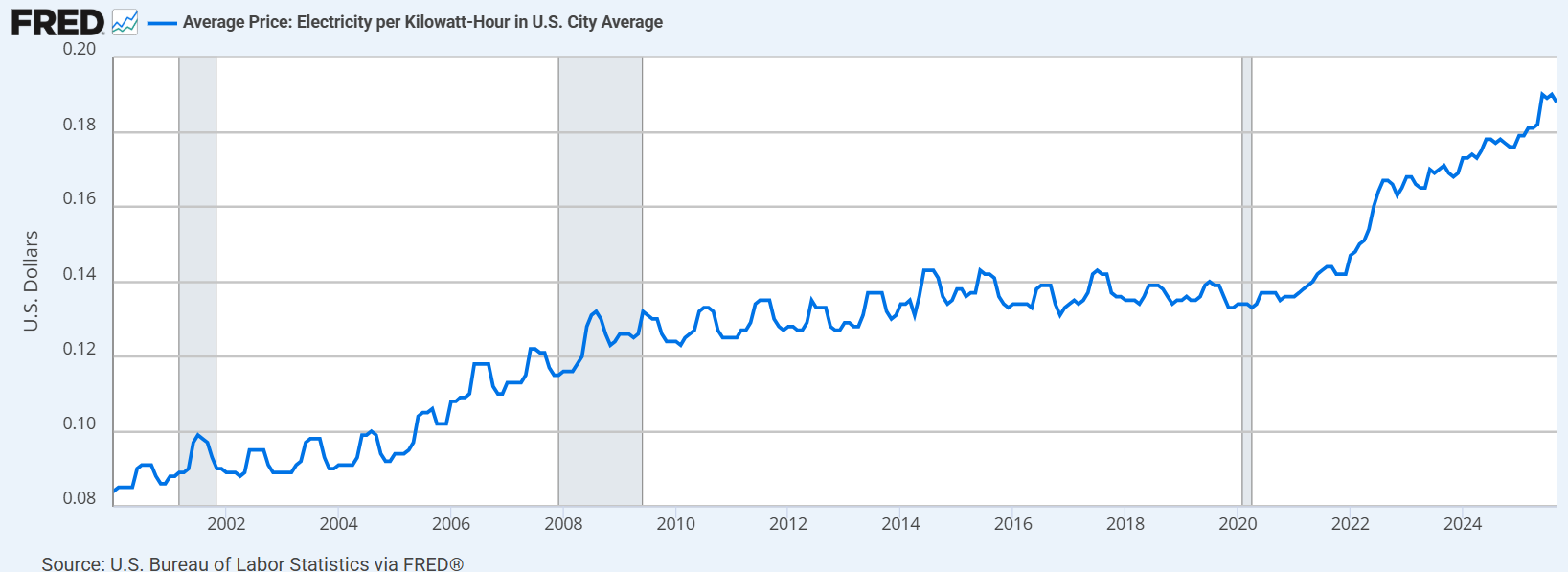

At the same time, interest rates on the revolving debt of government and credit cards are rising quickly. In six months, the average credit card interest rate has risen from a whopping 15% to an unbelievable 19%, more than a 25% increase. US debt payments rise by about $40 billion for every percentage point rise in the interest rates facing the government. The interest rates on the most common federal borrowing instrument, 10 year treasuries, have doubled, to 3.5%, just since March 4 of last year, and are six times higher than the April before that.

In another decade, federal government debt service is expected to be larger than defense spending and the total of all discretionary federal spending. Meanwhile, household credit continues to accelerate. Interest rates appear to have been held down far too low for far too long that we have lost track of the purpose of debt, to invest in our future, and have instead bought lots of cows for our dorm rooms.

How’s that working out for us?