Colin Read • December 4, 2022

Do We Have Social Security? - December 4, 2022

On September 30, 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during one of his fireside chats the Supreme Court Justice White who was attempting to provide remedy to the abuses of the Gilded Age twenty years earlier:

"There is great danger it seems to me to arise from the constant habit which prevails where anything is opposed or objected to, of referring without rhyme or reason to the Constitution as a means of preventing its accomplishment, thus creating the general impression that the Constitution is but a barrier to progress instead of being the broad highway through which alone true progress may be enjoyed."

Roosevelt was setting the stage for greater governmental activism in an era of the Great Depression that defiantly denied any market solution. He was beginning to set the tone for a new innovation he called Social Security as part of a broader program of economic security.

He had a couple of goals. First and foremost was the need to stabilize an economy in which consumers out of fear of an ever-deepening depression were hoarding their cash. This policy seems prudent at the individual level, but it induced a self-inducing prophecy. Reduced spending induced businesses to stop their rebuilding of inventories and hence caused mass layoffs. These layoffs were part of a downward spiral that further reduced consumer wealth and spending.

Roosevelt made his case in his March 4, 1933 inaugural speech about the danger of this unvirtuous spiral, but soon realized that government was the only entity with any credibility to pull the nation and global economies out of this spiral.

Roosevelt was also concerned about the social insecurity that can result as a growing population of middle aged men and women approached retirement without the means to support themselves. But, since life expectancy then beyond a potential retirement age of 65 was in months or years rather than decades, the need to ensure this social security was not huge.

Roosevelt was brilliant in his policy to simultaneously address both economic and social insecurity. He proposed a social security system that would tax workers over their careers and then pay out fixed sums in retirement. Since it would take some time for the policy to take effect and for workers to participate, Roosevelt realized the government could take in a substantial tax from all workers for many years before a correspondingly large outflow of retirement payments were necessary.

In fact, it was not until early 1940 that the first payout, a check of $22.54 to Ida May Fuller of Ludlow, Vermont was issued. She had retired just a couple of months earlier. Meanwhile, large inflows of a new tax were flowing into federal government coffers, while the legacy on the system was small, especially since most men died shortly after retirement age.

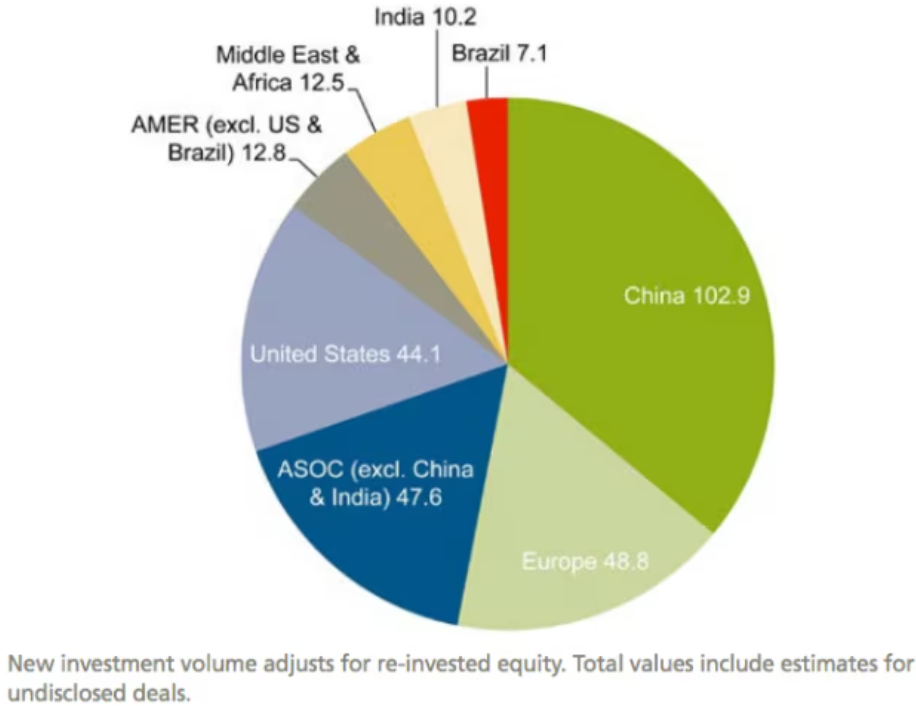

This policy only needs a few ingredients to work. First, if the sums could be invested and earn the strong returns that such a large and diverse source of capital could support with a diversified portfolio, the fund could increase substantially and could remain more than solvent to realize its aspirations.

The second element is a growing population. So long as the nation encourages immigration and the population is young enough to constantly churn out an even larger next generation, the system has more people paying in each year, and the payees only slowly emerging decades later. In other words, a large new population is supporting a smaller retired population, much as how a Ponzi scheme works.

Finally, if there is strong economic growth, quickly growing social security taxes easily support retirement payments that are proportional to past earnings over lower income eras. For instance, during the eight years of the Eisenhower administration, personal income (and hence social security payroll taxes) increased 45%. Growing inflows could easily support the modest payments mandated over only about a decade and a half of retirees.

Unfortunately, none of these three preconditions are met anymore.

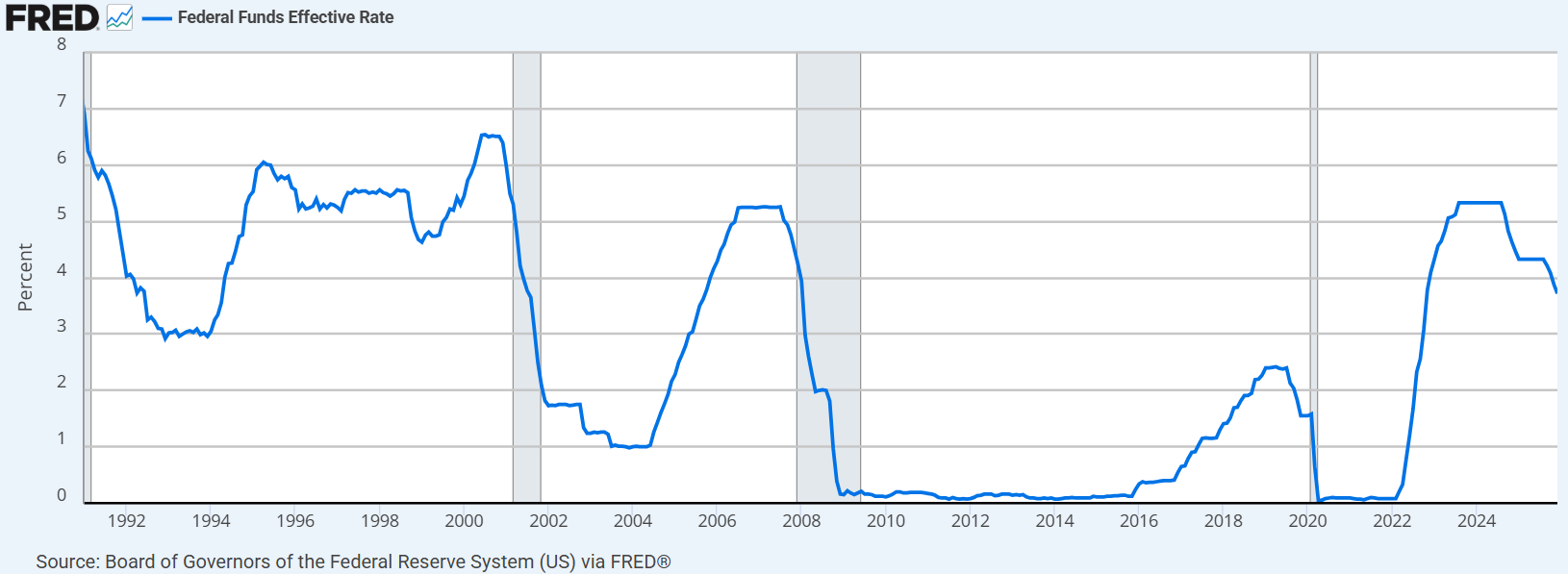

Rather than investing incredible sums into the types of investments to which some state funds such as resource permanent funds commit, social security surpluses are lent to the government at the lowest possible interest rate through the purchase of government securities. This then converts a lockbox that then presidential candidate Al Gore campaigned on into a program dependent on the government’s ability to repay these growing loans.

The second problem is that lifespans have increased vastly more quickly than increases in the retirement age that has barely budged in almost a century. The retirement age has risen from 65 to 67 years while lifespan now averages 79 years. In other words, a program that was formulated to cover perhaps a few years in retirement must now support at least a dozen years, and counting.

Finally, our economy has matured. The 5% annual growth of the Truman years has tapered to about 2% growth today. This has slowed the per person increase in contributions.

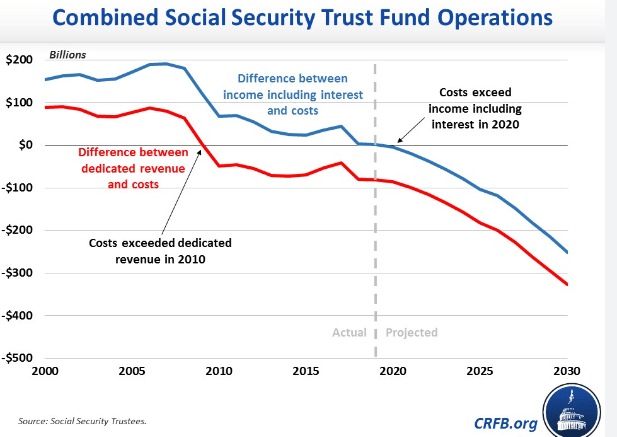

These effects have compounded to the point that it is now estimated the social security system will require hefty governmental net injections by 2034, or social security benefits will need to drop by 23% of what was promised.

Solutions that are being discussed include reduced benefits, means testing of benefits so that the benefits decline for those who are not low income, and increasing contributions to income beyond the income cutoff which result in maximum benefits. Instead, income up to $400,000 may be eligible for the social security tax, but maximum benefits will be capped to a level proportional to about $150,000.

The average social security income is less than $22,000 per year. In a high property tax city such as Plattsburgh and a median-priced home, almost 40% of that income is owed in property taxes and home insurance alone, even after senior citizen exemptions. That leaves a little more than $1,000 per month to cover all other living expenses. Many elderly on social security are living in poverty.

When I ask my students if they have confidence in the Social Security system, they almost universally state that they don’t think there will be any security for them, even though they believe they will be taxed to pay for recipients who got in before them. Most state they must start providing for their own economic security in retirement. But, saddled with significant student debt and with degrees that are no longer as valued in the marketplace as it once insisted, the ability to share both in the American Dream of buying a home and raising a family and also maintain security in retirement is increasingly becoming unrealistic.

By the way, Ida May Fuller was the exception rather than the rule. While her earned payout was very small each month, she defied actuaries and lived to be a hundred years old. She died 35 years into retirement, in 1975.