Colin Read • December 9, 2022

The Interventions are Working - Kinda - December 11, 2022

What a year so far. We have been tracking the far too slow response of the Federal Reserve to acknowledge the great supply chain pinch that was created by the great pandemic, and then exacerbated by the great cash giveaway caused by an unfortunately timed election.

Over the last year, we have seen a Fed that finally recognized this profound mismatch between constricted supply and consumer demand that has been augmented by government checks in the mail. Of course, if it had seen what many economists saw, it might have responded in time. Nonetheless, the Fed’s policy to increase interest rates is starting to take hold.

In the absence of a thoughtful policy to alleviate supply bottlenecks, for which the Fed has no control, especially compared to thoughtful national industrial policies, all the Fed can do is try to limit demand. The federal government can soak up excess demand by reducing its spending or by soaking up excess consumer cash through tax increases, but few elected officials have the courage to do that. The Fed is far more constrained because all it can do is raise the interest rate.

An increase in the rate it offers banks if they come seeking short term loans to shore up their mandated cash reserves has the effect of discouraging lending. Banks choose to lend less because of the Fed’s actions, and hence fewer homes are constructed and mortgages issued, and fewer cars are purchased or malls and other commercial properties built. These policies are working. While there has been a shortage of new cars, so these sales are not suffering, used car prices have fallen, as has home prices.

These are the economic transmission mechanisms the Fed hoped would succeed, and they are working to avoid the runaway inflation that is every Fed’s fear. Consumer balances are decreasing, wage increases arising from too-tight labor markets is abating, and nominal spending is not keeping pace with price increases, which means the actual quantity of stuff purchased is declining.

In this blog we have been tracking not the trend toward moderating increases in the price level at the consumer and producer level over a year, but rather the more revealing annualized increases over three and six months. The Friday publication of the monthly Producer Price supports this trend. The data from this week showed still strong job creation, but moderating producer price increases that have now fallen to an annualized rate of 3.6%.

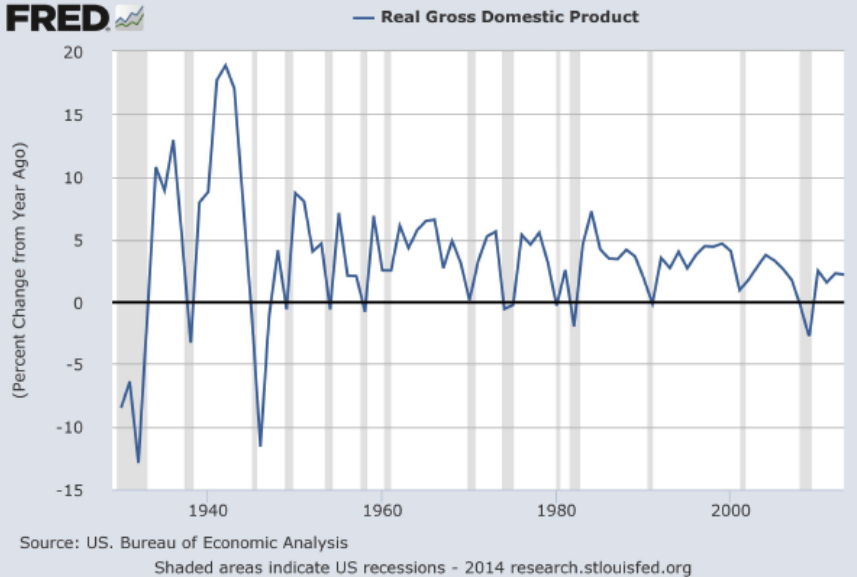

Clearly, the policy to slow demand is working. Perhaps even the strength in the jobs market also means that supply constraints are abating too. Strong economic growth in the last quarter, after two quarters of negative growth, seems to support this supply strengthening. We must still wait and see how our expectations net out over the next few months, but I expect things will be much clearer by April.

Meanwhile, I believe the Fed will soon depart from its stated goal of raising interest rates substantially and at every opportunity. They will probably raise their discount rate again at next week’s meeting, but by half a point rather than the three-quarter point they had indicated earlier.

Then, the Federal Discount rate will be in a more traditional range. If we find that indeed inflation is beginning to moderate as the analyses in this blog has indicated, and if the job market continues to hum along nicely, the technical recession we observed from two quarters of economic decline may end more quickly than most could have imagined.

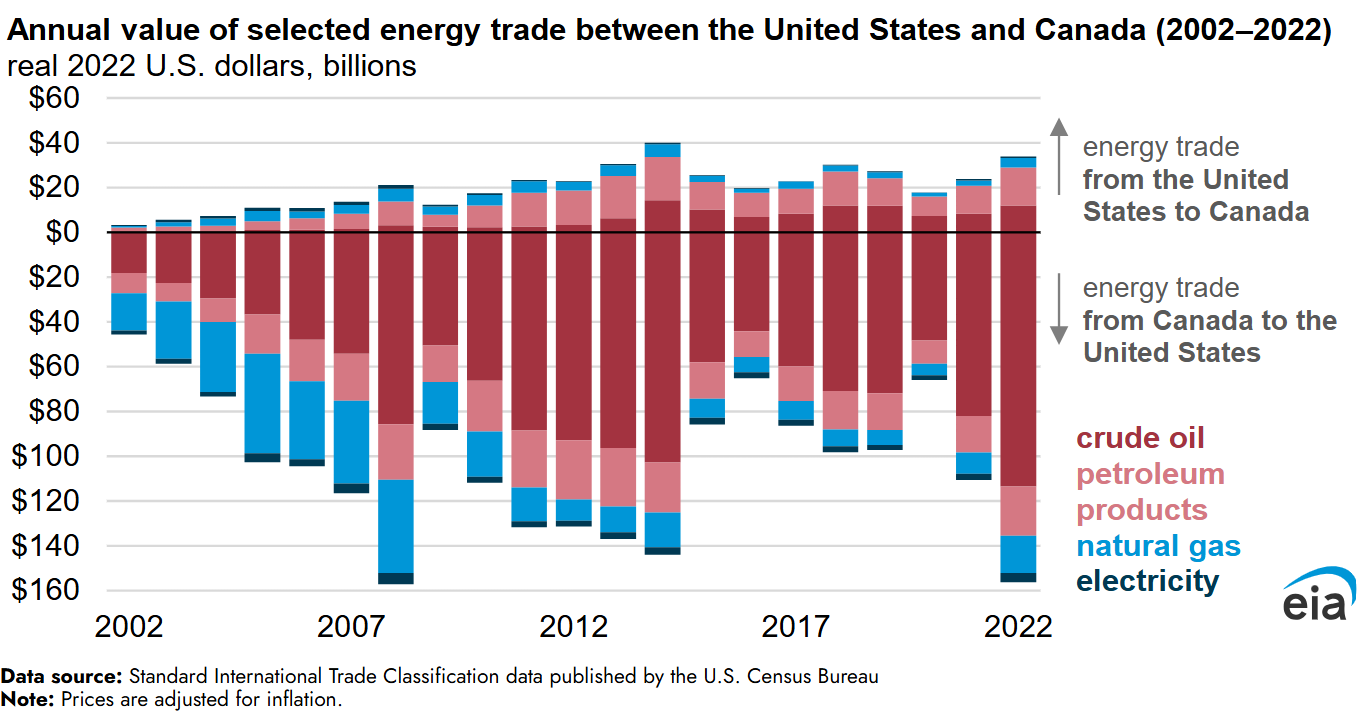

We are not yet out of the woods though. Other countries, especially those dependent on the price of energy imports, are still suffering high inflation. Countries like the United States and Canada, despite our unusually low energy prices, by international standards, are still part of an international economy for which many of its members are facing double digit inflation. Should these problems push them into stagflation, we will be along for that ride. It may show up in our stock market rather than in continued inflation, and that loss of wealth will further constrain price increases. Unfortunately, the Fed can’t take its foot off the brake until international markets stabilize too, for fear of an inflation backlash. Hold on to your horses.

We are still left in the U.S. with a very high level of new debt that has doubled over the past decade and a half, and a portion of the labor force who have either prematurely retired or the middle aged men who may never successfully find their way back into the post-COVID labor market. That said, it is nice to see that the worst could be past us, at least in the absence of significant fiscal mismanagement.