Colin Read • May 28, 2023

Dodged That Bullet? - May 28, 2023

Most rational people realized that it would have been insane to not find a way to reach a deal and avoid defaulting on U.S. government debt. Sanity prevailed.

The penalty suffered for a government debt default is high, but the claims are exaggerated. Millions of jobs lost and a deep recession is a bit hyperbolic. Certainly a 500 to 1000 point fall in the Dow Jones, and a percent or two rise in bond interest rates would likely occur in the short run. That would be a sufficient scare to motivate those who drove the economy into the creek, but not over the cliff.

Markets have become accustomed to these political antics. Bond rating agencies have already moved the outlook on U.S. finances to negative just because of brinksmanship. This also happened in 2011 under similar circumstances. Then, one ratings agency even reduced the overall bond rating by one notch as well.

A one-notch downgrade places about a 10 to 20 basis point penalty on the borrowing cost of new government debt. What might that cost national finances in the long run?

It depends. I’ve developed a simple rule of thumb of the costs of changes in government debt as a share of our gross domestic product. Let’s say our total government debt is 100% of our GDP. Currently, the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds is just under 4%. That is still a bit lower than historic averages, but let’s use 4% for this example. If a nation has a GDP of $25 trillion and a 100% debt-to-GDP ratio, total interest paid would be 4% of $25 trillion, or about a trillion dollars per year in the long run.

It is easy to see that as the debt-to-GDP ratio rises, so do these interest payments. If the debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 200%, interest on debt would then rise from 4% of the economy to 8%. In essence, the debt-to-GDP ratio acts as a burden multiplier. Take the government cost of debt, measured for instance by the 10-year treasury yield, and multiply it by the debt-to-GDP ratio, and, voila, we can instantly see the debt burden on our economy.

The U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is approaching 150%. A 20 basis point rise in the interest rate on debt then results in a 0.3% diversion of GDP toward debt service and away from private investment. As the debt-to-GDP ratio increases, this reduction in private investment becomes larger.

It has been seared into our brains of late that U.S. government debt is now at $31.4 trillion, while GDP is $25.5 trillion, which results in a debt-to-GDP ratio of 123%. The Congressional Budget Office estimates this ratio will rise to 200% by 2053.

Using these multipliers, we can see why national debt matters. The greater the borrowing to pay for government programs, the less that is available for private investment in the construction of new homes, research and development into innovative products, and investments in new factories, greater efficiencies, and improved productivity.

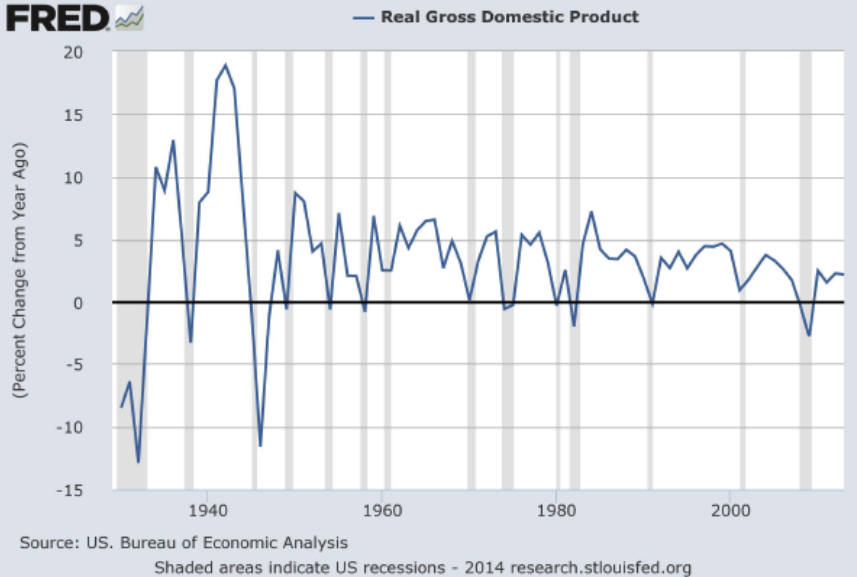

Gross Domestic Private Investment as a share of GDP typically hovers around 16%. In recessions, this investment rate drops, which further deepens recessions, while the optimism of economic booms enhances GDPI and extends the boom. In other words, GDPI is an economic amplifier, while the debt-to-GDP ratio is an attenuator.

Let’s understand why.

First, debt is owned both by the public, domestic and international, and by various governmental agencies. Often this smaller category of agency debt, which represents about 22% of the total, is not included in the debt figures because it is argued that the debt is within the government family. However, this debt is committed. Rather than investing in private markets, the social security fund has invested in government bonds with low returns. Once this fund is exhausted, or if the government defaults on that debt, taxpayers are on the hook to make up any discrepancies, at least if the government lives up to its promises. Hence, these obligations are still burdens on taxpayers.

Second, some argue that issuing such debt is an inexpensive way to fund government, especially in times of low interest rates. These rates are low because of a historic willingness of nations such as China and Japan to buy our Treasuries with the surplus dollars they receive from their trade surpluses with us. Should these surpluses dry up, so does that easy money. But, that easy money is not free. While a trade surplus brings money into our country just as such capital inflows do, such bond purchases must someday be repaid, with interest. All we do when we rely on this cheap money is buy a bit of time.

The biggest problem is the diversion of savings to pay for government rather than to invest in private infrastructure. Little of government spending is making an investment in the future. The vast bulk of it is in taking care of needs today that politicians believe will engender them with a voting public increasingly pampered for immediate gratification. In 2001, our nation’s 225th year, government debt had risen to $5.7 trillion. By 2023, just 22 years later, debt has more than quintupled to $31.4 trillion. Every year we must divert $3 trillion of our savings to fund government rather than fuel American competitiveness. In just ten years, the Congressional Budget Office predicts that our debt burden will triple compared to the 2022 value, and will exceed every other category of government spending except Social Security and Medicare that are funded with separate payroll taxes. This debt service will reach about 7% of GDP, a level that triggered massive bond ratings downgrades among European nations.

U.S. market commentators expressed great concern a decade ago about profligate spending in European nations. Now that our spending and debt-to-GDP ratio is rapidly approaching the worst EU nations, it is time to recognize our bigger problem is not our debt. It is runaway spending relative to tax revenue.