Colin Read • June 4, 2023

The Reserve Currency and Monetary Autonomy - June 4, 2023

There was a time when central banks could rely on some autonomy in their monetary policies. Those days are gone for the major trading countries of the world. Now, policy and economic peril are contagious.

We think of central banks as entities such as the Federal Reserve charged with the creation and maintenance of steady and reliable financial markets. In any domestic economy, we choose to value all goods and services in terms of one thing - money. If the value of money fluctuates, we think twice about the myriad exchanges we make.

For instance, while it sounds fantastic to have such a currency increase its buying power over time, let’s think through the problems that arise if the same amount of money could buy more stuff over time. Such is the case with deflation. When we think that big ticket items such as stock and bonds, homes, or the price of new cars will continue to drop, and hence so will the aggregate price of these goods, we respond accordingly. We decide to delay purchases. In essence, a deflation means our money is increasing in its purchasing power, just as it would if it earned a rate of interest that exceeds the inflation rate.

If the same amount of currency later is worth more than now, we delay spending on such big ticket investment items and assets. Such a decrease in spending results in a recession.

We have also witnessed the opposite. When prices increase, we tend to purchase earlier than we might have liked, motivated by fear of the consequences of inflation. Workers and producers may also attempt to indemnify themselves from higher prices by demanding higher wages or by upping the price of produced goods. These decisions drive prices up even higher.

These artificial influences on our economic decisions are costly. We conclude that the best central bank policy of all is to keep prices constant and hence the buying power and value of our currency most consistent and stable over time.

Of course, many other forces impinge on an economy well beyond the control of a central bank charged with monetary predictability. If monetary policy is an imperfect science, the authorities we entrust to keep our purchasing power predictable know we would prefer just a slight bit of inflation than the more cataclysmic risk of deflation. All we want from our money is the maintenance of a slight inflationary bias of around 2%.

Most major currencies walk this fine line. If we were to judge how effective they are, we can look to two things. How consistent is the currency? And how large is their money supply? Recall your high school or college lessons on the “law of large numbers.” A large number of events are much easier to predict. Success over an entire football season is easier to judge than on any given Sunday. A financial portfolio made up of a large number of assets tends to vary less than one in which all eggs are in a single basket.

The sheer size of the U.S. economy, combined with a universal faith in the ability and diligence of the Federal Reserve to maintain a relatively constant value of money means that the world relies on the U.S. dollar as the de facto “reserve currency.” Large international transactions such as purchases of energy are often denominated in dollars because buyers and sellers of energy are not interested in becoming foreign currency dealers. Everybody agrees to denominate many international currencies in terms of the most reliable currency.

The gold standard once served this purpose of a universally accepted asset to trade. In reality, up until when President Nixon unilaterally announced the end of an agreement to denominate all major currencies relative to gold. Until then, one might exchange pounds sterling for dollars to buy U.S. cars, knowing that both dollars and pounds were each pegged to a gold equivalent. Such a Bretton Woods system forced nations to hold gold in an amount relative to their currency outstanding, so exchange rates between nations were essentially constant and dependable.

Once the international money system moved off the gold standard, central banks had to manage money. If a lot of their currency was leaving their country to fuel a trade deficit, and if that money was not returning perhaps in the form of domestic asset purchases by foreigners, central banks had to make up the difference to ensure steady relative exchange rates. They did so, and still do, by holding currencies of other major nations in reserve accounts to make up for any imbalances.

Obviously, the best reserve asset would have two qualities. The first is that the currency is good at holding its value. The second is that the currency is one most frequently used for cross-border trade and investment. But, central banks would prefer to hold such reserves not only in dollars but also in U.S. government securities that can quickly and easily be converted to dollars but also yield a modest rate of return.

This is why the U.S. dollar is still regarded as the best “reserve currency.” It works for the world who all have an interest in holding steady the terms of trade of the world’s largest economy as a way to influence and steady the value underlying their own currencies. It also creates a ready market for U.S. Treasuries that steadies the value of these government securities and hence lowers their required rate of return. Some have estimated that this lower effective interest rate saves the U.S. economy about $100 billion per year. While a large number, it represents only about 1/250th of the U.S. GDP.

If the attractiveness of the use of U.S. dollars as the reserve currency is effective because of the degree to which global trade is networked most frequently through the dollar, what would happen if another economy becomes the world’s most significant, and if it too could ensure effective monetary policy to hold inflation close to zero?

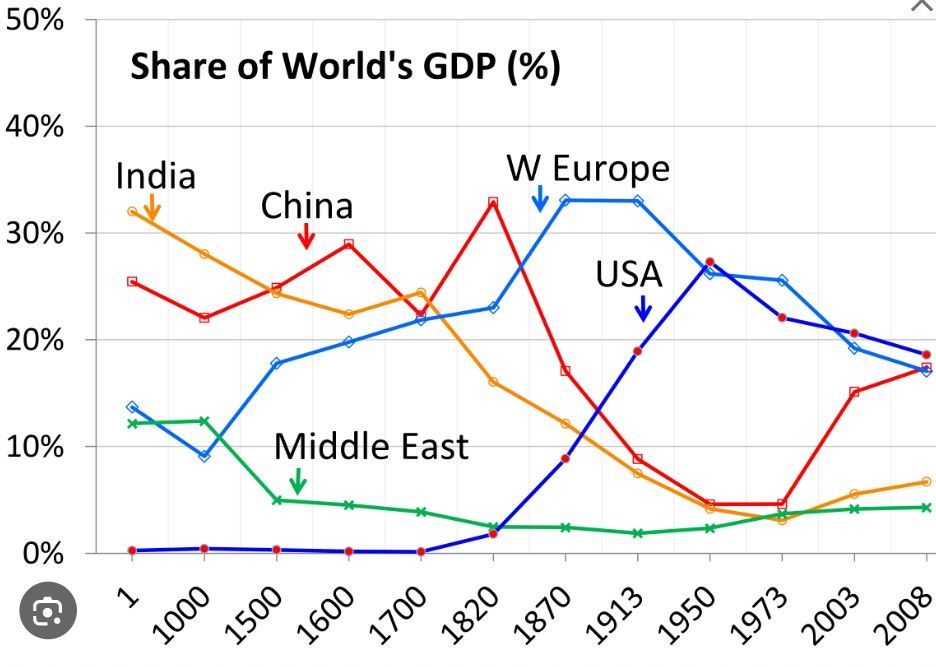

In its era of dominance, the United Kingdom’s pound sterling was the world’s reserve currency, up until 1916. Had a unified European Economic Union assembled by then, it would have constituted the largest currency until 1950. Since then, the U.S. has been the largest economy, but is on the verge of losing that status to China in the coming years.

Of course, the size of an economy is not the only factor. The degree to which other nations network with the U.S. economy continues to make it attractive. China would like to have both the prestige and the monetary interest rate externality arising from reserve currency status, and is working hard to expand trade and dependencies with emerging nations with populations that can increase demand for China-produced products over time.

China’s larger challenge is in garnering the confidence the U.S. already enjoys in its open markets and monetary policy relatively insulated from political interference. The U.S. is extending its monetary dominance through its leadership in the G8 network of economies. Central banks worldwide have learned the hard way that it is best to zig rather than zag when the Fed zigs. To ensure international economic harmony, nations must keep predictable the relative flows of trade and capital between nations. This can only be ensured through the maintenance of consistent relative values of their currencies and interest rates. If alternative coalitions of nations can form and recognize their mutual interdependence, the U.S. dollar’s special status may not last forever. In economics, nothing does.

Of course, threats of U.S. government securities defaults only hastens global reconsiderations of the U.S. dollar as the de facto reserve currency. China, too, has a sovereign debt default problem, but theirs is from local debt that the national government may need to absorb. They can absorb that pain, given the greater authority of their central government, but not without economic and credibility risks that erodes confidence in their currency.