Colin Read • June 15, 2024

Does Electricity Move at the Speed of Light or a Snail's Pace? - June 16, 2024

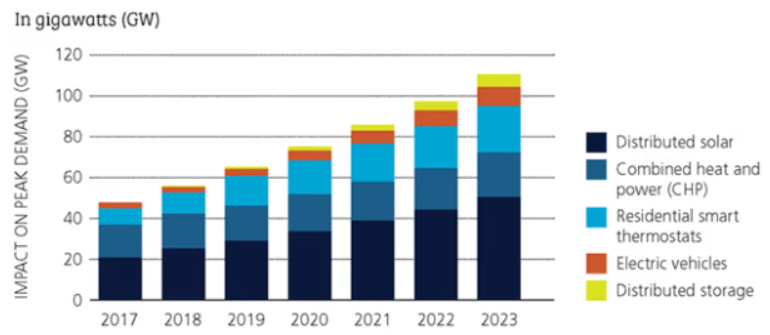

(today’s graph of rapidly expanding energy needs with an already-overtaxed grid - courtesy National Council of State Legislators https://www.ncsl.org/energy/modernizing-the-electric-grid)

Electricity is something we have taken for granted for a century now. But when we lose it, our whole world changes. This world has been changing much more frequently lately due to more severe storms, heat waves, and demand from electric cars and bitcoin mining that exceeds capacity.

We were all taught in school that electricity propagates at the speed of light, but electricity capacity and investment moves at a snail’s pace.

Granted, the electricity industry is somewhat unique. Electricity can be made at relatively low investment cost but high marginal costs for each kilowatt-hour generated. This is the model of hydrocarbon-based generating facilities that burn natural gas or coal to make heat that generates steam and drives turbines. These plants are relatively inefficient, with typically about 50% of the energy wasted in the process. They remain competitive, though, because hydrocarbons are underpriced since they don’t reflect the cost of the negative externalities they impose on the economy.

The other way to produce electricity is through sustainable sources such as hydroelectricity, wind, solar, and geothermal. Nuclear power is not technically sustainable because it consumes fission products such as uranium, thorium, and plutonium. However, the power that can be generated from just a bit of these resources is huge.

The economic model for these plants is much different. They require mammoth up-front investments, but the cost for each additional kilowatt-hour generated is very low. Because of the high upfront costs, the private sector is wary of the investment risk, even if the technologies are superior to hydrocarbon-based generation in the long run. This is the reason why it makes sense to offer subsidies to build, followed by taxes on the margin on production or consumption to pay for the subsidies.

To his credit, President Biden has invested more taxpayer dollars into correcting these market failures than any leader has done anywhere, except perhaps in China. There remains one problem, though. How do we move to market the increased electric capacity our increasingly-electrified economy demands as we phase out fossil fuels?

The problems with the electric grid are decades in the making. Electricity does not move costlessly. Nikola Tesla outsmarted Thomas Edison almost a century and a half ago by showing that high voltage alternating current can be transported with less loss than low voltage direct current. Even so, transmission losses consume about 5% of the electricity we generate in the U.S. That amounts to an extra power plant for every nineteen built. That’s costly and wasteful.

These losses also occur despite another legacy of hydrocarbon generation. Because such thermal power plants are relatively compact and the fuel can be moved to them through existing railroad lines or pipelines, these plants are often built near where the greatest mass of people live. That way, transmission losses and costs are minimized.

However, with large scale sustainable power, we must generate where the wind blows or the sun shines most dependably. These sources are also more land-intensive than wasteful thermal plants. This artifact of sustainable energy means that we incur greater transmission losses.

These problems can be solved, but private utilities have no incentive to solve them. Utilities make money in the production and distribution of electricity. They have less incentive to buy power generated hundreds or thousands of miles away because they then lose out in generation profits.

There are also new technologies that allow us to transport electricity much more efficiently. New semiconductors can take the low voltage direct current electricity Edison promoted and convert it to high voltage DC that can be transported with even less loss than high voltage AC. A few companies have found a niche in building such high voltage DC lines, for instance to move Quebec power to New York City. But, there are not too many private companies with the deep pockets for the investments necessary.

I have written in past blogs that the real visionary thing we could do is convert to a DC economy. Modern refrigerators or stoves typically convert AC to DC anyway to operate their motors or electronics, or can run just as easily on DC as AC. The electric cars we charge need DC, so we experience losses changing the AC in our homes to DC to charge our cars. And, all of our electronic devices use DC. We can now convert DC from one voltage to another cheaply and efficiently. We should consider moving to a DC economy. If we did so, we could save tens of billions of dollars annually in losses alone.

I can’t imagine our economy converting in our lifetime, though. Knowing the forces that maintain an even wasteful status quo are far more significant than the force of change, we should at least figure out ways to reduce transmission losses. Certainly we have encouraged much more efficient appliances, as evidenced by the yellow energy stickers on new fridges, stoves, washers, dryers, and television sets. We recognize that electric cars are cheaper to operate than gas cars. But, we have spent almost nothing on reducing transmission losses.

The fix is not difficult. Using inexpensive electric monitors to measure transmission line temperatures can allow us to move electricity more optimally without overheating transmission lines. Switching old overhead wires to newer designs and alloys can also increase capacity and reduce losses. These things can be done relatively quickly, easily, and cheaply.

But, why bother? The utilities are allowed to pass on the cost of their transmission losses to consumers, but would have to wait for any savings from investments to improve their grids. They are certainly loath to redesign the grid as necessary. Our grid was built out more than a century ago, with the last major improvements occurring in the 1960s and 1970s, more than half a century ago.

There are two public policy problems that defy navigation. One is that any new project must go through an extensive public process. I recall shortly after moving here in 2005 that a company proposed to build the HVDC line from Quebec to NYC. Almost twenty years later, the project is completing all the approvals, but the movement of power is still years away. Meanwhile, China recently built the largest solar facility in the world, including the necessary distribution improvements. It took them eight months to complete.

This local resistance in part Not-In-My-Back-Yard (NIMBY) and partly due to the fractured system of 3,000 public utility companies in the U.S. Improving the grid is like herding cats, each of which is very opposed to the non-local solutions a unified grid would impose on them.

These are the fundamental reasons why civil and electrical engineers proclaim that the U.S. electric grid is antiquated. The U.S. government in the past month announced a Grid Modernization Initiative that would spend $13 billion on grid improvements in the 21 states willing to cooperate.

This investment is just a drop in the bucket compared to the need to modernize more than 100,000 miles of transmission lines. A grid modernization bill has languished in a dysfunctional Congress for years, so help of sufficient scale is not likely on the way. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission recently voted to require local utilities to plan for future needs, but such initiatives are easily frustrated, and does not at all solve the need to unify a fragmented grid.

Grid improvements globally are estimated to cost upwards of $20 trillion by 2035. Estimates for the improvement in resiliency and capacity for the U.S. grid are around $5 trillion.

Executive action to seed $13 billion for grid improvement is a start. But it only pays for one quarter of one percent of the investment necessary to reduce electricity costs, increase resiliency, reduce increasingly common blackouts, and anticipate the expansion of electric vehicle market share. The private sector will not pony up $5 trillion to improve the grid, especially if it means a battle with 3,000 local utilities.

If there was ever a need for public sector investment in a critical industry, this is it. If we can’t do it, I’m sure China would be willing to show us how it is done. No, wait, we aren’t speaking with China right now.