Colin Read • June 18, 2024

Made in Japan? - June 23, 2024

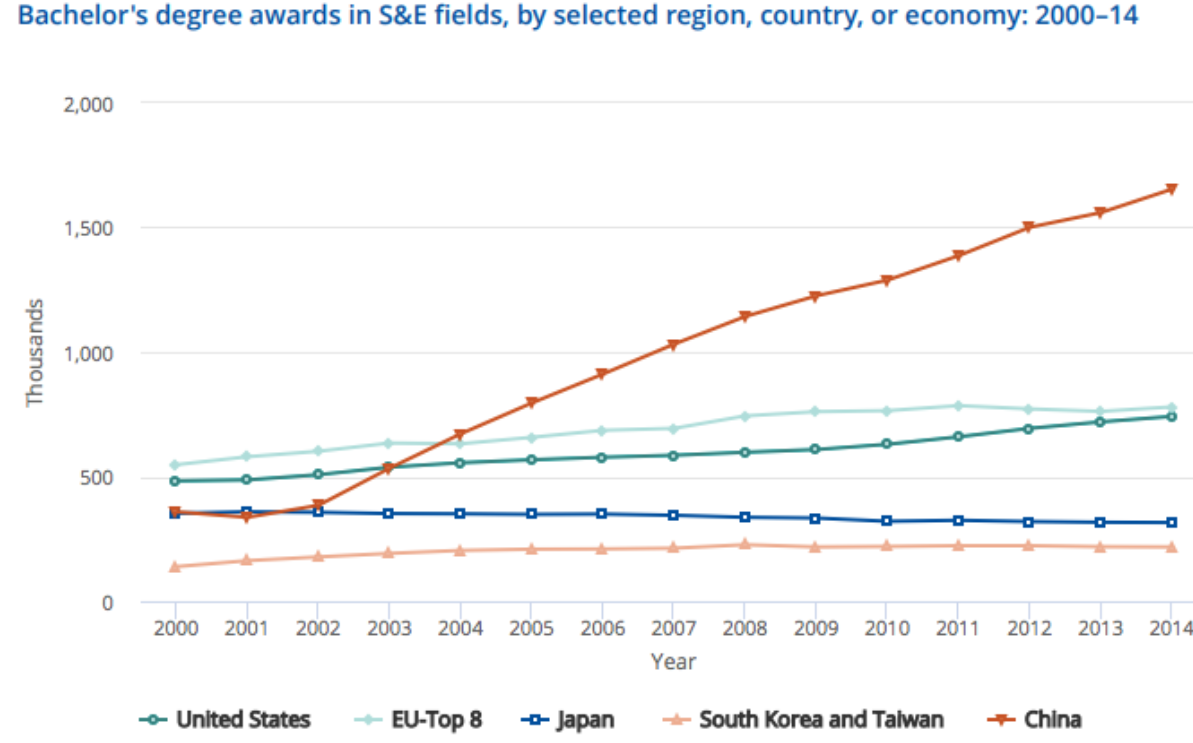

(courtesy World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/02/these-charts-show-how-china-is-becoming-an-innovation-superpower/)

I recall as a child the saying “made in Japan” was a derisive poke at cheap and inferior manufactured products from that country. A little later, once Japan started producing leading edge consumer products like Sony televisions and Walkmen, and Honda revolutionized fuel economy in the wake of the OPEC oil crisis of 1974, that term was replaced by “made in Taiwan.”

Now, Taiwan is headquarters for the world’s leading semiconductor manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, TSMC. The engineer who developed the most sophisticated microprocessor manufacturer in the world cut his teeth in the U.S. before his recruitment to Taiwan to found a new juggernaut. He recognized he could do what he does best better in Taiwan than he could in the U.S. The rest is history.

Morris Chang was motivated by the impressive ability of Texas Instruments’ Japan manufacturing facility to double the productivity of a similar plant in Texas. He felt the engineering and work ethic in Taiwan could unleash huge advances in electronics manufacturing. He was right.

Chang tapped into the industry of innovation. While we used to claim that Japan’s success, and now China’s success, is derivative of innovations in the United States, that attribution of imitation is unfair. New technologies are almost always imitative. There are few new discoveries in the world of science and especially engineering. Rather, we often strive to take a good mousetrap and make it better.

The USSR produced a rocket capsule that could drop back to Earth using parachutes. NASA soon followed. One American car manufactured developed intermittent windshield wipers. Soon all cars had that feature. Elon Musk developed a rocket booster than can return to land softly on Earth, and now Stoke Space is developing a rocket with full-flow-staged-combustion that is eerily similar to Musk’s Raptor rockets. Of course, Musk did not invent this novel rocket design. He took an innovation pioneered in the USSR and improved it. Now, Stoke Space out of Washington State is moving the ball still further.

Somebody invented the wheel, but now we all use them. And when engineers see an efficient solar panel or wind turbine, rooms of engineers try to make them more efficient and bigger. Technology is less innovation and more imitation, whether between companies in the same nation or in different nations.

If companies do so, we call it competition, unless a China-based company does it. We then call it unfair competition.

Now, I am not a China apologist. Their treatment of the Uighur population takes the form of work camps and internment that our country subjected to the Japanese in World War II, a generation after the U.S. achieved its ascendancy as the world’s economic superpower. China’s culture of collectivism a generation after it joined the league of developed nations flies in the face of our culture of individualism. The Chinese tolerate overt surveillance, while some argue we are subject to more covert surveillance,more often by social media companies than our own governments in the West.

The question is less what brought manufacturing capacities in Japan, Taiwan, or China to where they are now, but rather what should we expect of their competitiveness in the future, especially when compared to American competitiveness.

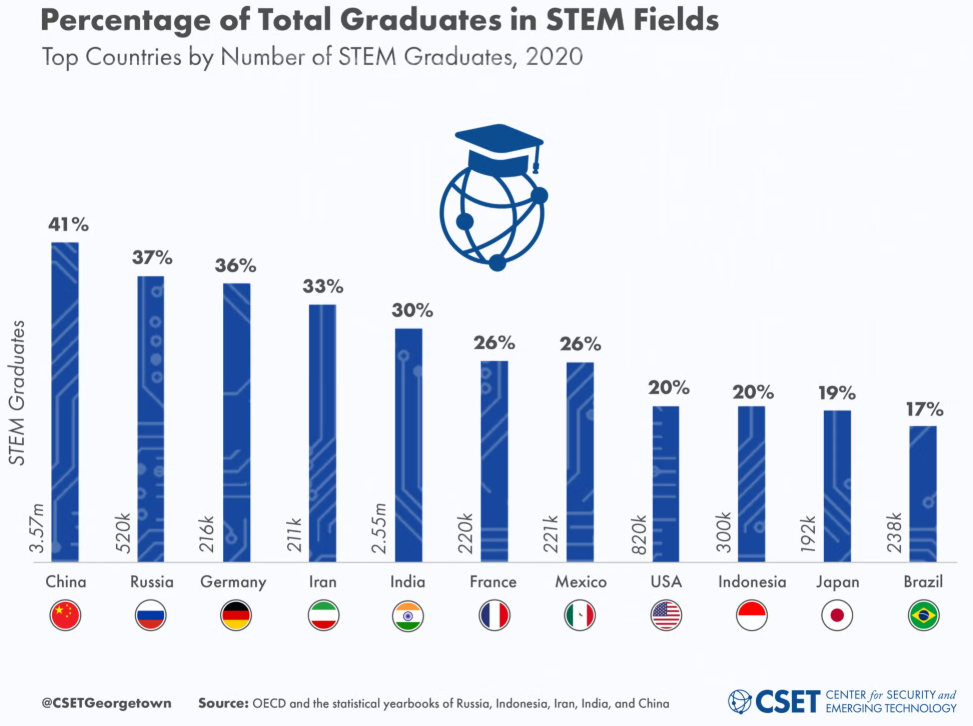

A few indicators should give us pause. China is producing about 1.4 million engineering graduates each year, while the US produces about 140,000. India is producing about 1.5 million engineers annually.

One can assail Chinese graduates as quantity over quality. However, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and Harvard professor Graham Allison recently warned, “Most Americans assume that their country’s lead in advanced technologies is unassailable. And many in the U.S. national-security community insist that China can never be more than a “near-peer competitor” in AI. In fact, China is already a full-spectrum peer competitor in terms of both commercial and national-security AI applications. China is not just trying to master AI; it is mastering AI.”

China is also leading the world in solar, battery, electric vehicle, wind, and new generation nuclear power innovations. They recognize that AI and energy sustainability are not only necessary for their future. These technologies represent the next wave of technological innovation and sustainability worldwide for the foreseeable future. China has recognized this vision and developed a state-fostered industrial policy around that increasingly universally shared vision.

In an article earlier this week, the Economist magazine noted that China now produces more patents than any other nation, the science journal Nature notes that China now publishes more top journal articles than any other nation (up from a third the U.S. total a decade ago), and six of the world’s top ten universities, as measured by research output, are now in China. We can see from today’s graph that, beginning in 2002, China embarked on a national policy to create the R&D juggernaut we witness today.

Our response would at one time have been to redouble our competitive efforts. Sputnik spurred our space race, and U.S. astronauts soon landed on the moon. The post-WWII technological spurt may have been spurred by Cold War fears, but it nonetheless resulted in an American industrial renaissance, not by holding the USSR back, but vaunting the West forward.

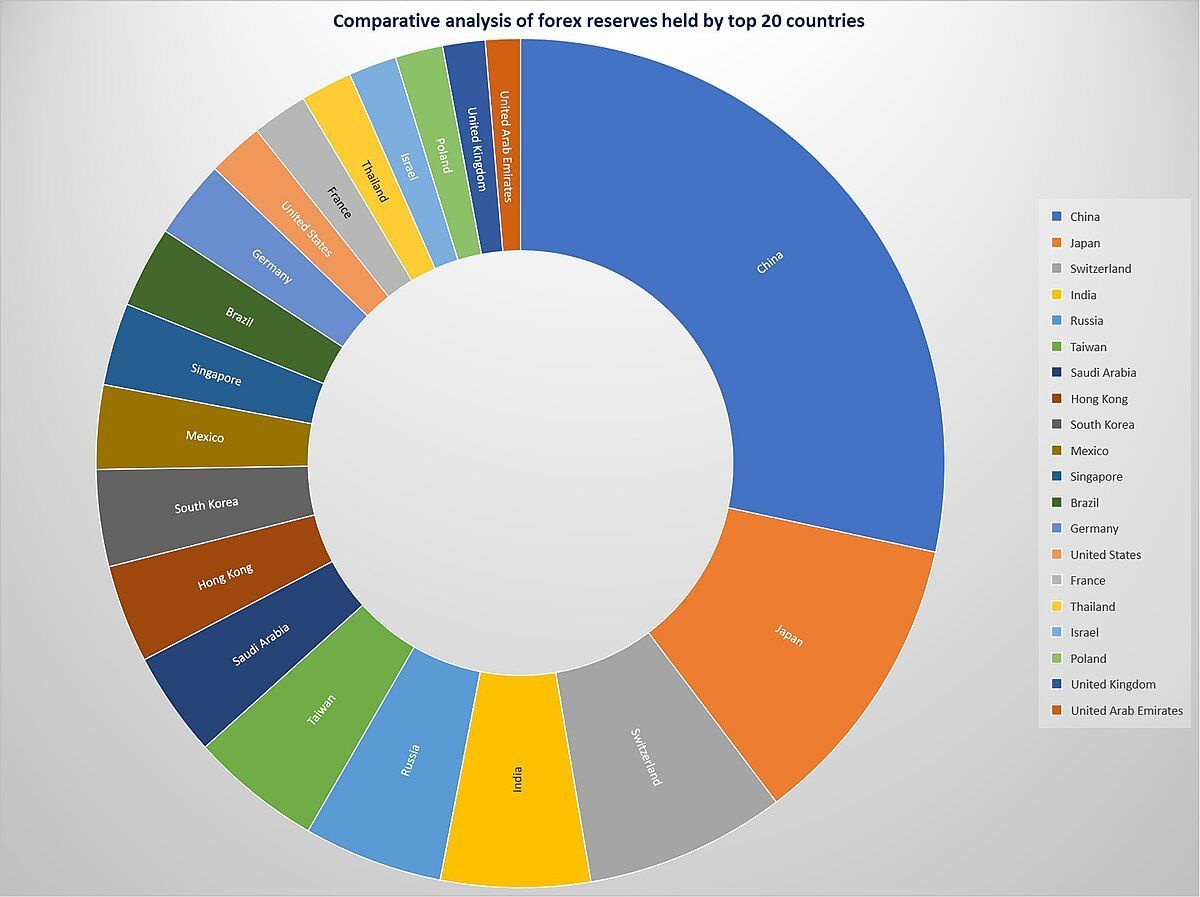

When U.S. policy now seems determined to trip up or ban Chinese innovation, that merely redoubles the resolve of Chinese scientists and engineers to work even harder, and, increasingly, repatriate back to China. Their nation is now a hotbed of R&D, with a willingness to invest both publicly and through the private sector using a gross savings rate of 44%, defined as the difference between GDP and consumption, compared to the U.S. rate of 18%.

Maybe it is time for us to imitate the Chinese. We have largely abandoned past practices of coherent and directed industrial policies that worked so well for the U.S. back in the 1960s. When we try to fund technological innovation, we are now far more likely to use demand-side subsidies that encourage foreign companies to open up U.S. factories for solar panels or electric vehicles, rather than the supply-side investments that guarantee innovation and competition.

I have not lost faith in the North American competitive spirit. With a concerted effort to produce more scientists and engineers like President Kennedy initiated in the 1960s, we can again attain the pinnacle of innovation. The problem is complacency. We don’t see how other nations aspire to knock us off our apex. And, our affluence has translated into a sense of liberty and entitlement where we resent any federal policy that tries to direct us to reinvigorate mathematics, science and engineering in our schools. We view a subsidized education as a right rather than a privilege, and do not tolerate any effort that encourages us to study disciplines key to American competitiveness. The U.S. spends on average almost twice as much per K-12 student than other OECD nations, and yet we produce test results in science and math near the bottom of the top 20 nations. Canada spends significantly less than the U.S., but ranks #8. China is #2 in test scores.

There is no doubt that China is motivated to do so to knock the U.S. off the apex of competitiveness. It seems more doubtful that the U.S. will comprehend the stakes and redouble its efforts to maintain the innovation that produced technologically-based affluence unparalleled in human history. We used to say that when the going gets tough, the tough get going. Granted, China should no longer be permitted to benefit from more lax provisions in the World Trade Organization agreement when they entered the WTO as a developing nation. And, some of their trade practices are as archaic as the unproductive attempts by the U.S. to keep Canada softwood lumber out of US markets. But, we should be free to encourage our private sectors through an industrial policy, just as do the Chinese. Perhaps it’s easier to fight than switch.

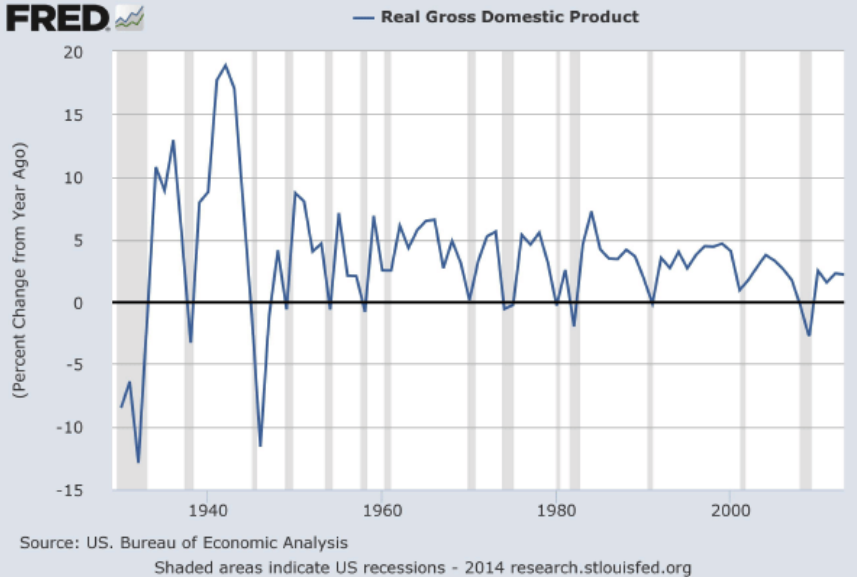

None of this is to say that China's economy is somehow superior to those in the western world. It faces significant headwinds, as does ours. We should not mistake our economic health with our pace of innovation. China's investments in new technologies are the lifeblood of their future economic growth. For us to wall ourselves off from their better mousetraps does little to resolve our differences, hurts our consumers, and redoubles the resolve of innovators. Even in the face of proposed modest European Union tariffs on China EVs, the CEOs of Mercedes Benz and of Tesla state they'd prefer to not have those protections. It reduces their need to innovate here and in Europe, and will surely result in backlashes in China as well. Nobody wins trade wars, as we saw in the aftermath of the misguided Smoot-Hawley protectionist legislation of the 1930s. Then, populist politicians proclaimed that protectionism will somehow enhance the vitality of a depression economy. Their beggar-thy-neighbor policy failed then, but politicians still try to return to the same worn-out song whenever they lack the creativeness to pass real industrial policies designed to invigorate innovation that is the lifeblood of long run economic growth. Such populist traps are easy to fall into, but very hard to escape once tit-for-tat sets in.

They do so because, in the face of increased global competition, it is easier to blame others for our predicament. Instead, we devote our legislative efforts toward impeachment of Attorney Generals and Homeland Security cabinet officials. The movement among the West toward authoritarianism and populism sprouts from a frustration that affluence we once took for granted now seems to have long since exceeds our grasp. Certainly, China politics are frustrating and destabilizing, especially in their potential surveillance of residents of their trading partners. Maybe we spy on them too, or have mechanisms to make that possible with our social media companies. I don't know. Either way, using our citizens as pawns in these trade and retaliation games are silly and nasty and put our children at peril.

Both China and the U.S. has some significant demographic issues as both countries seem to view potential immigrants from other nations as liabilities rather than assets. China's one-child policy now seems particularly problematic. These factors will hold back the effect of consumption amplification on growth. But consumption economics woes should not be confused with innovation investments that pave the path for future economic growth, consumption woes or not. It's a dangerous mistake to somehow minimize the need for our nations to innovate by focussing on faltering economic fundamentals in China, some of which they've rolled their own, and some our politicians hope to impose upon China so they can win their populist political games domestically. We don't run a faster race by tripping up our competitors. We run faster by training harder.

Those who don't play in such superpower games actually benefit the most. Mexico is generating tens of thousands of jobs as EV manufacturers BYD and VW serve Central and South America from local factories. These countries get jobs, affluence, new technologies, and, best yet, superior and cheap cars. Tesla is not the #1 EV retailer in Brazil, nor #2, or #3, or #4. Consumers in these countries are laughing at super-economic-power games all the way to the bank, as will their children and their children's children, and as China is investing heavily in Central and South American industrial capacity. The best value and highest technology products Brazilians enjoy are embargoed from American consumers through a combination of protectionism and populist politics because the powers that be wish to punish China's entrepreneurship and coddle ours.

We'll teach China and others by shooting ourselves in the foot. In the wake of a failure to invest as much as other nations, we spend our time complaining about others. As though protest too much, we exhibit a rearranging of the deck chairs on the Titanic quality. Complaining and retaliating and pointing to false or misplaced arguments about economic headwinds elsewhere are easier than developing national industrial policies that will sow intergenerational growth. Maybe it’s high time we stop contemplating our navel and infighting in the face of daunting global competition and start working together to create a better and more sustainable future for our children’s children. Perhaps we should imitate China's industrial policies, albeit American style. A rising tide lifts all boats, even if it lifts the boat of innovators even more. Just sayin'.