Colin Read • April 23, 2023

How AI Will Change Some Things Though - April 23, 2023

Last week we discussed the role of Artificial Intelligence in our technical evolution. Let’s look this week at its effects on the distribution of income.

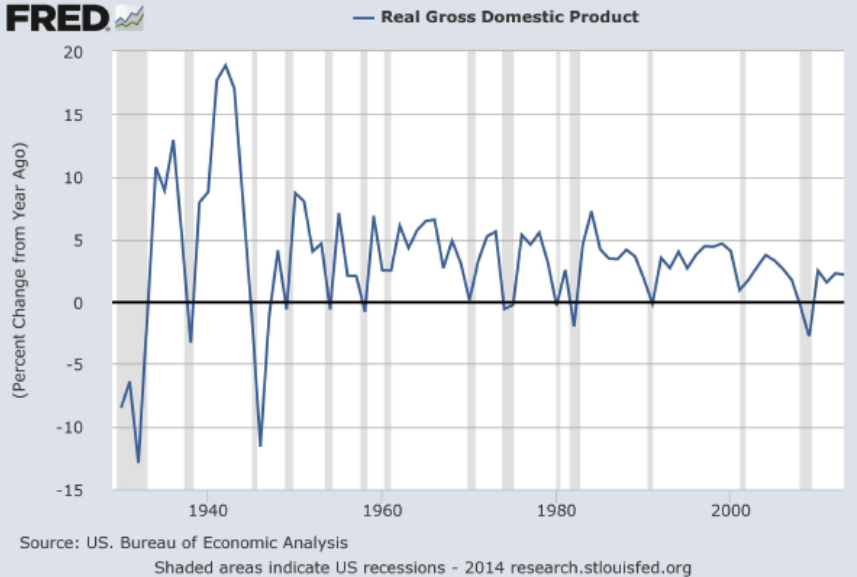

There is little doubt that technological innovations spur economic growth. The first wave of mass power from water and steam freed humans from powering machines such as looms to operating them. A one horsepower loom could move from requiring a dozen humans to just one. The same workforce could then produce output a scale of magnitude higher, and hence at much lower cost. This frees resources to do other things, and hence economic growth occurs.

Economic growth takes a large set of factors and translates them all into one measure - the size of the economy in terms of its Growth Domestic Product (GDP), or alternately the amount our GDP grows. This mapping of a multitude of measures into one loses a lot in the translation. One can’t map a bunch of complex factors into a simple linear measure without losing a lot of insights.

This is the problem of much of economics in general, and especially macroeconomics. The tools of economics are helpful in reducing the world’s complexity into simple measures only if we are willing to judge progress based on its efficiency rather than fairness or equity. If our only goal is to more efficiently grow the economic pie, then GDP and its growth may provide such a measure.

However, such an oversimplification is fraught with complications. What if we produce much more, but all the income gains go to one or a few individuals who do not consume any more goods or services just because their already incredible income rises ten or a hundred-fold? We are left with more production and income, but with no increase in consumption power.

In such a scenario, it is possible that savings arising from a technology such as robotization or AI will result in lower prices as well as greater profits. If so, those fortunate enough to retain employment in such waves of innovation may be able to consume more if product prices indeed fall.

The prospects for those who become redundant with technological innovations are less fortunate, though. Between the 1980s to 2010, sawmills only need a dozen workers rather than a hundred, or automakers employ about half the number of workers it did just a generation ago. The 2008 recession aside, manufacturing GDP continues its march upward while manufacturing jobs steadily trends downward, from almost 20 million jobs representing 19% of the labor force in 1980 to barely 11 million jobs and 7% of the labor force in the US a couple of generations later. That's a lot of disaffected workers.

How are middle-aged manufacturing workers reabsorbed into an evolving economy? Probably nowhere. They won’t be taking jobs designing and programming the robots that replaced them. Nor will they be absorbed into the depreciating skills jobs that require extensive initial training and then ongoing training or work experience to maintain skills. That rules out most jobs which require a college degree. Nor will workers who invested their human capital in manufacturing in the 1990s find jobs in their 50s that are labor-demanding such as construction.

This leaves only low income and unskilled work for such displaced workers, or no work at all. Many of these workers are still years away from social security, and any savings and pensions they created have not enjoyed the large buildups that don’t really occur in our savings until advanced middle ages.

With AI, we are in the second wave of such displacement. Or, perhaps we are in the 10th wave since our economies were blessed with mass power, fossil fuels, electrification, the transportation revolution, the electronics era, the agricultural revolution, computerization, the information age, automation, and now AI. With each wave comes a small number of huge winners, advantages to all who can maintain jobs, and severe displacements to those left behind.

These displacements are the reason why the Western World is increasingly disaffected. By the very design of our market economies, we leave behind a growing cohort who cannot keep up. AI is for the first time accelerating this trend once confined to the unskilled, and then to the blue collar worker, and now to white collar workers that write reports, legal drafts, and articles, teach our children and young adults, even diagnose our illnesses and read our X-Rays and MRIs. The McKinsey Global Institute has estimated that almost half of all jobs will be replaced by 2055.

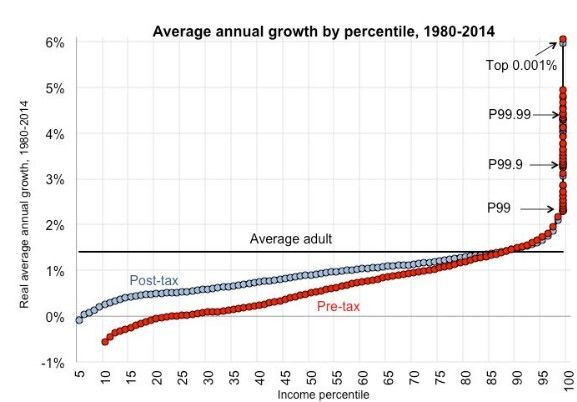

Certainly some of these jobs will be replaced by others. But, the jobs created by people displaced are lower-paying and less productive - else they would have been drawing workers in the first place. As output and profits rise with greater efficiencies, and people become redundant or must accept low skill jobs, the distribution of income naturally worsens.

This is not to argue that humans should reject ways to use our resources more wisely, efficiently, and sustainably as technology shows us how. To do so would place us among those who followed the legendary Ned Ludd’s demand to destroy dehumanizing textile machines more than two centuries ago. While we ought not be Luddites, we may want to deal directly with the growing number of disaffected individuals who pay the price of innovation. If we do not, our society will become increasingly polarized between those well-trained and wealthier and those who punched their economic ticket in bygone days when tickets were punched rather than digital.

Or, we can ignore the need to create new economic opportunities as we enthusiastically embrace economic innovations. If we do so, we will continue to be confronted with the divisions of democracy. Today's graph shows that only 15% of our population have gained more than the average gains since 1980 while 85% have fallen behind. While (the almost incomprehensible) income for the top earners is now doubling once every decade, half the population has been doubling their real income only once every century. It is these discrepancies that foment the division and dissent that some politicians use to their advantage.