Colin Read • April 30, 2023

A Problem by Design - April 30, 2023

I recall lamenting in 2008 that the Fed had put itself into an awkward position. Asset values were rising rapidly, led by housing prices (remember the cable show “Flip That House?”). Financial innovations such as increased securitization of mortgages and credit default swaps were creating the perception that good ole’ financial risk was commodified and almost universally well-managed - until it wasn’t.

The Fed was drinking the new “hedged risk” confidence, and was instead expressing concern about the rising financial market valuations one would expect if indeed risk was finally effectively managed. Over-inflated asset markets translates into paper wealth-induced consumption and hence triggers the Fed’s Taylor Rule. This rule of thumb calls for a higher discount rate when output exceeds its natural rate.

With the failure of some very large financial institutions such as AIG to effectively hedge risk, the credit default swaps market melted down, and brought with it the funding for very large projects that depend on effective associated markets for their risks. Large project lending prices rose substantially, projects were delayed, and a chill fell over asset markets built upon a bit of a house of cards. Once fear spread across increasingly volatile markets, the Fed was confused. Are markets overvalued and the economy overheating, or is it on the verge of the Great Recession?

You may by now be wondering what economic history from a decade and a half ago have to do with the Fed’s quandary today. Well, a lot. First, these events and the Fed’s response dramatically expanded the scope of Federal Reserve policy. Gone were the days in which the Fed used leverage in the commercial banking system to control domestic investment through interest rates. The Fed broadened its scope as a lender of last resort to financial markets more broadly, and adopted new tools of control as part of a novel philosophy of quantitative easing.

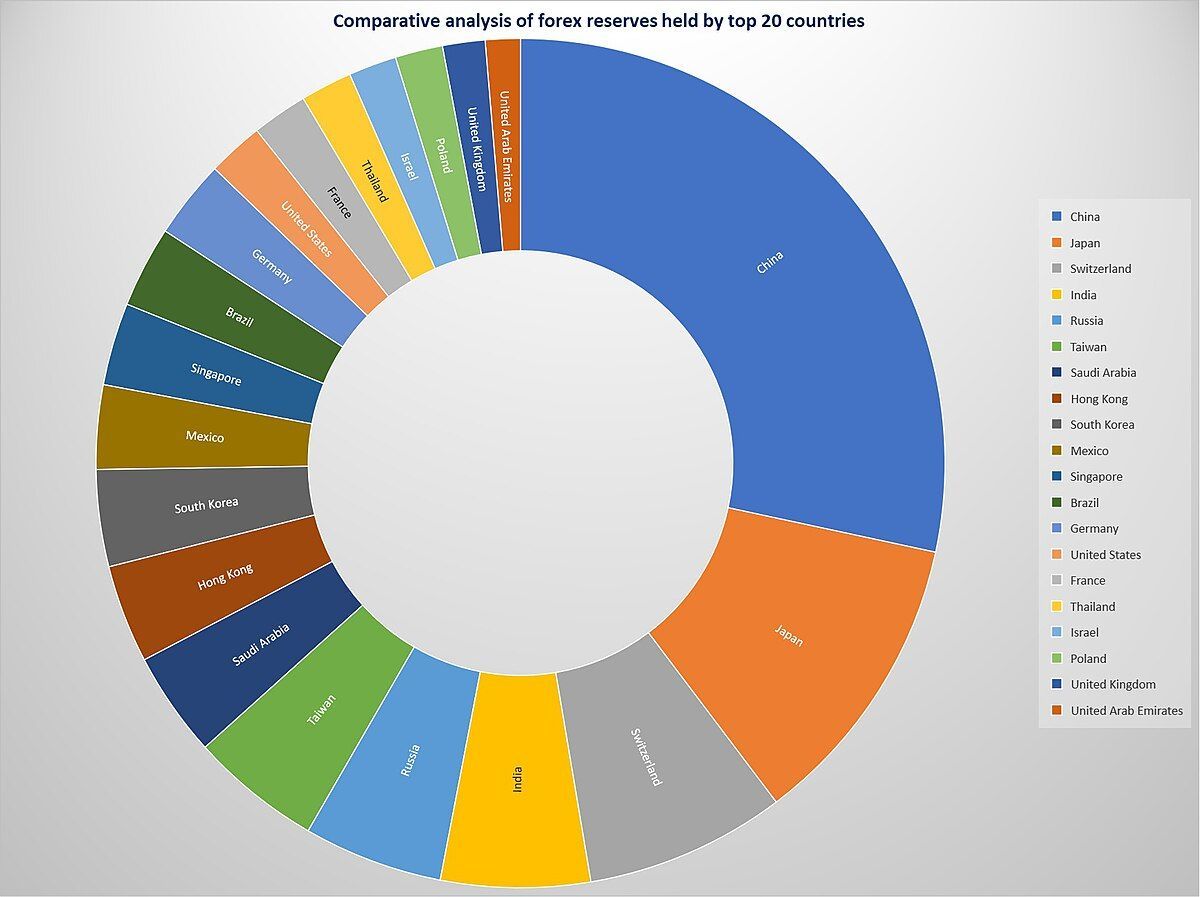

It took the Fed a year to reinvent itself, and it has not stopped since. In retrospect, the Fed likely wished it understood and could improve transparency in new hedging tools that developed over the first decade of the new millennium. Congress subsequently got into the act as well, with its Dodd-Frank legislation that made investing more complicated and costly, but which probably would not have prevented what occurred. Instead, the Fed has greatly expanded its scope well beyond its reach. Unable to actually stimulate the economy when people had largely given up on the monetary system, the Fed instead kept interest rates low for a decade as investors ran for the hills. Indeed, frustration with the Fed, and central banks worldwide, was the motivation for Bitcoin as a substitute for traditional high-powered money called M1, which is primarily cash and checking account deposits that can be quickly converted to consumption.

Now, there are many substitutes for M1, which makes Federal Reserve intervention even more impotent and less predictable. This has resulted in Fed targets they continue to maintain on a hugely swollen balance sheet that includes many non-traditional assets. Confounding the problem are governments addicted to low interest rates, and expecting the Fed to fund their vote-buying through massive income injection projects.

Fiscal policy can definitely stimulate an economy, even if fueled by artificially low interest rates. One could say that the Fed is not responsible for decisions of presidents and Congress, except that their low interest rate regime is the crack which Congress is addicted.

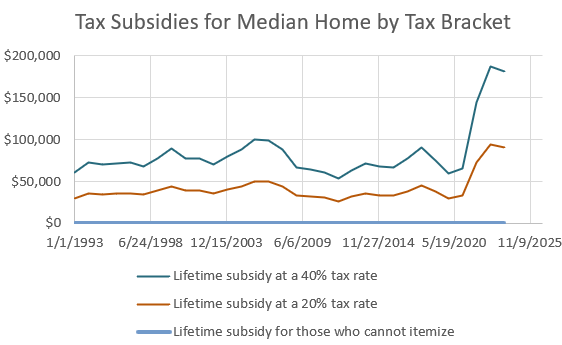

Now, the Fed recognizes the folly of their decade-long policies. We now know that the Fed is not particularly effective at pushing an economy, but is very powerful at pulling it back, just like pushing on a piece of string does not work but pulling it does. But, economists know there’s no free lunch. The Fed can only undo fiscal excesses and a damaged supply chain by putting the ropes on spending. It targets primarily commercial and residential investment by jacking up interest rates, but the banking industry inevitably pays the biggest price. A rise in short term interest rates to slow spending and combat inflation inverts the yield curve as it raises the cost of funds for banks while these same banks are locked into revenue streams on their asset side. This interest rate regime, and structural changes following COVID, have already decimated the commercial property market, with some existing buildings three quarters vacant and selling for a quarter of what they might have fetched a few years ago.

It is even worse than that. Banks have many such commercial property loans on their books and are pinched because an expectation of higher future interest rates depresses the value of bank assets and triggers failures such as what we witnessed at SVB, Signature Bank, and First Republic. These banks may have been more vulnerable than most banks, but are marginally more vulnerable than many. These bank failures are only the tip of the iceberg partly in the Fed’s making through extended inappropriate cheap money and a failure to act early, which induced them to do too much too late.

I note this now because the Fed has embarked on a note of atonement. It recognizes it did not sufficiently flag increasing risk SVB, its auditors, and its audit committee likely realized. Some banks were in too deep and too early in this cycle to adjust really rapidly deteriorating balance sheets as medium term government securities repriced with the Fed’s rapidly interest rate escalation. In the aftermath, some accounting standards will likely change, as will bank regulation. But, the Fed is more concerned at this moment with stemming the bleeding from their self-induced wound.

More data that merely verifies it takes a long time to steer an economy onto a new course shows that the Fed’s issue is not whether it will need to raise its interest rate another quarter next week, but whether they must continue doing so. The supply chain inflation has mostly run its course, but now the secondary wage-push inflation has set in. The mechanics of supply chains can adjust much more quickly than the expectations of workers and unions who must negotiate their salaries for a couple of years to come. Still-tight labor markets and wages that are rising at more than 5% suggest that inflation is not yet done, and nor is the Fed.

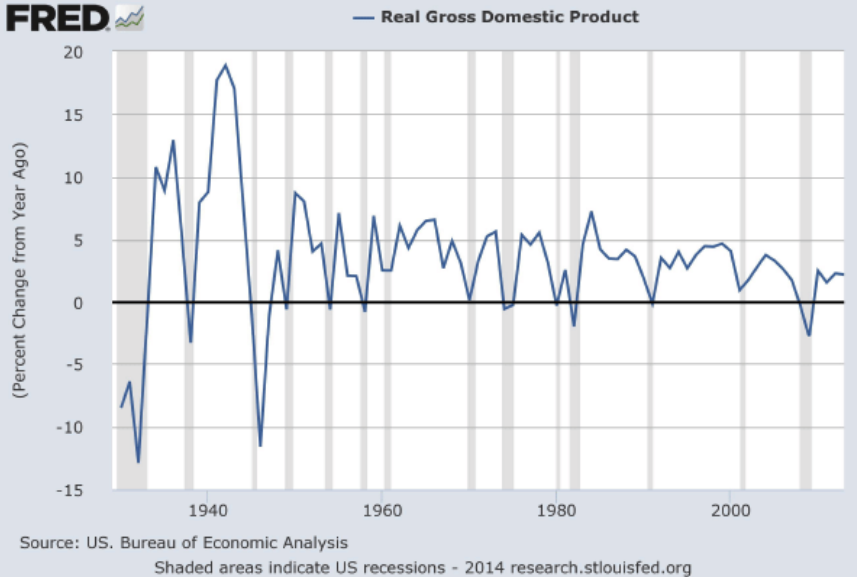

At this point, the recession we have been arguing in this blog for some time is pretty much inevitable. To look back to the Great Recession for clues are not helpful because the last recession was devoid of inflation, and indeed was even briefly deflationary. The circumstances we face now are much more akin to the energy supply chain inflation of the mid 1970s followed by the wage push inflation of 1979-81. Paul Volcker pushed the economy into a steep recession to reverse runaway wage inflation, an image seared into every Fed chairperson since.

When the emperor has no clothes, they can do little but inflict pain and try to instill confidence. If they fail to instill confidence, and if they continue to inflict pain, more bank failures are inevitable, and a minor recession can easily become a major one.

I don’t blame the Fed entirely, though, and I do appreciate their self-reflection, even if there is still insufficient acknowledgement of the politicization of Federal Reserve Board appointments over the past couple of years that delayed normalization of discount rates for too long. The Fed was zigging nicely in the latter half of the last decade, then zagged for a few years to accommodate a year of COVID and then an election cycle. Now, today’s graph shows that it is playing rapid catchup to get to where it ought to have been.

The real culprit, partially of their making, beside the tragedy of failed banks, is a Congress that subscribes to wishful thinking that debt no longer matters, the Fed can bail them out through low interest rates, and there is no such thing as the crowding out effect.

If we don’t believe that necessarily high interest rates designed to divert sufficient capital so the fiscal spending disease can be prolonged does not have an effect on the private sector economy, just ask new home builders, big project contractors, or, for that matter, SVB.