Colin Read • July 22, 2022

Negative Interest Rates? - July 24, 2022

Negative Interest Rates? - July 24, 2022

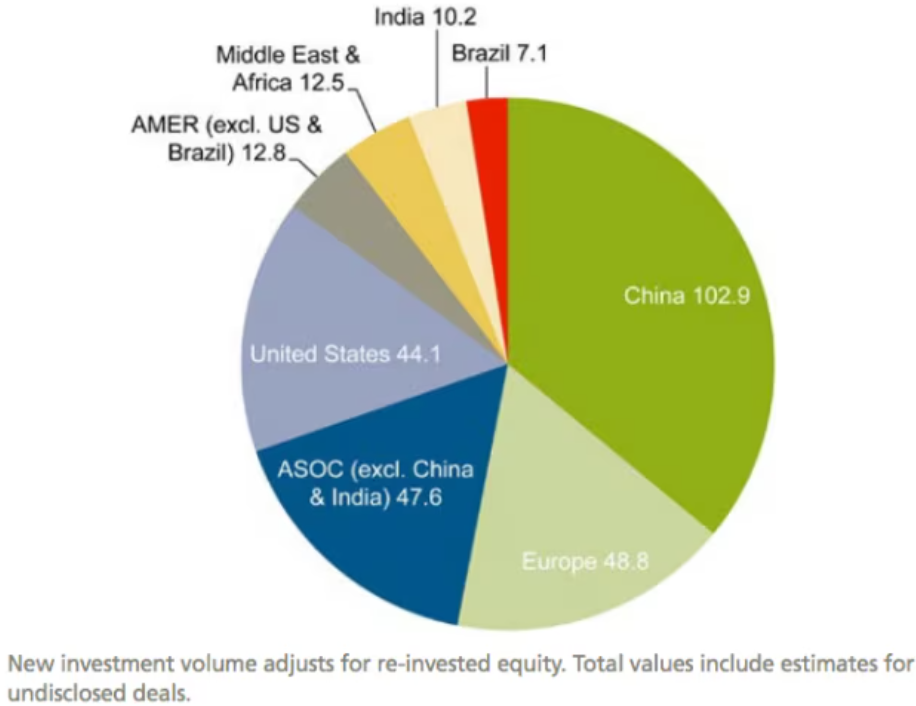

I’ve said that the Fed has done too little and too late to stem inflation. As I return in a few days from Europe, I observe that the European Central Bank is even behind the Fed. Let’s discuss some international aspects of interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates.

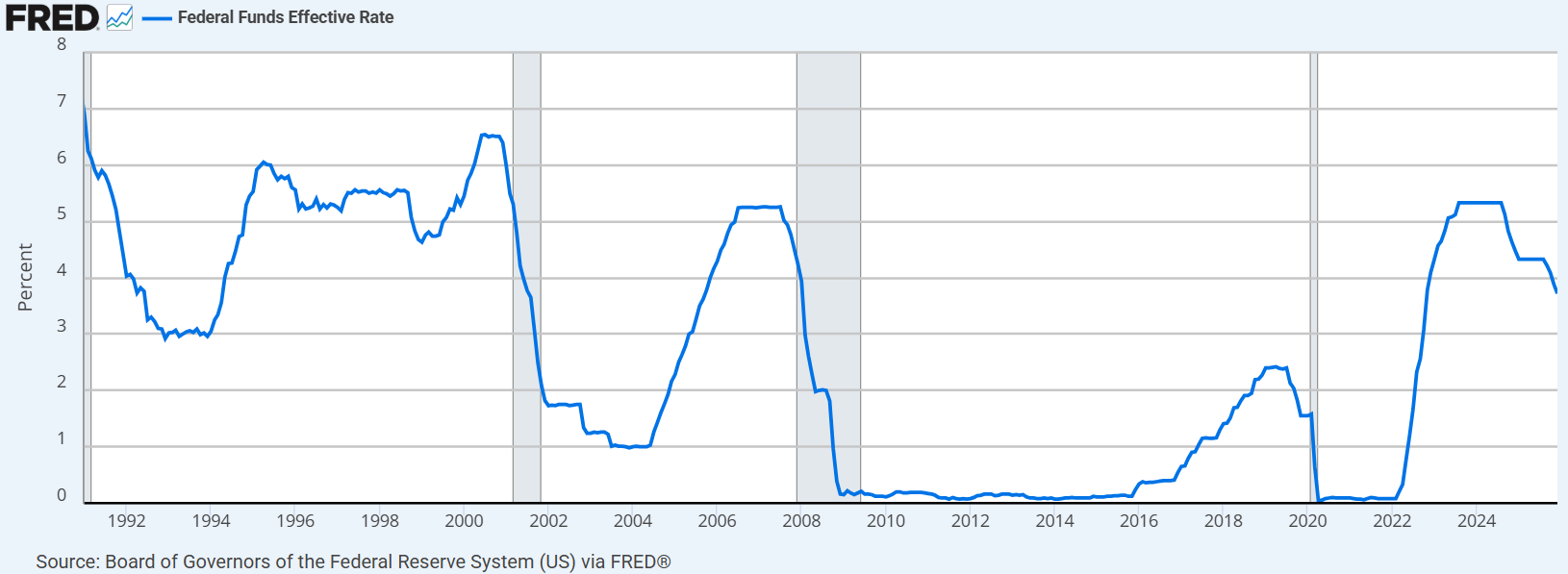

The ECB has risen its discount rate by 50 basis points, or 0.5 percentage points. That would be moderately large in normal times, but now the U.S. Fed is flirting with 75 and 100 basis point increases to catch up for its “too little too late”. The unusual aspect for US monetary policy makers is that the ECB is bringing its discount rate up to 0%. In other words, before this increase, the ECB had held their discount rate at a negative value, -0.5%, for more than a decade.

What does a negative interest rate mean? Their central bank was penalizing their member banks from holding excess cash reserves. Holding cash then depreciated both by the 0.5% charge they must pay at the ECB, but also by the inflation that eats away at the buying power of cash held by banks. The ECB was sending a clear monetary message - lend out cash to stimulate the economy.

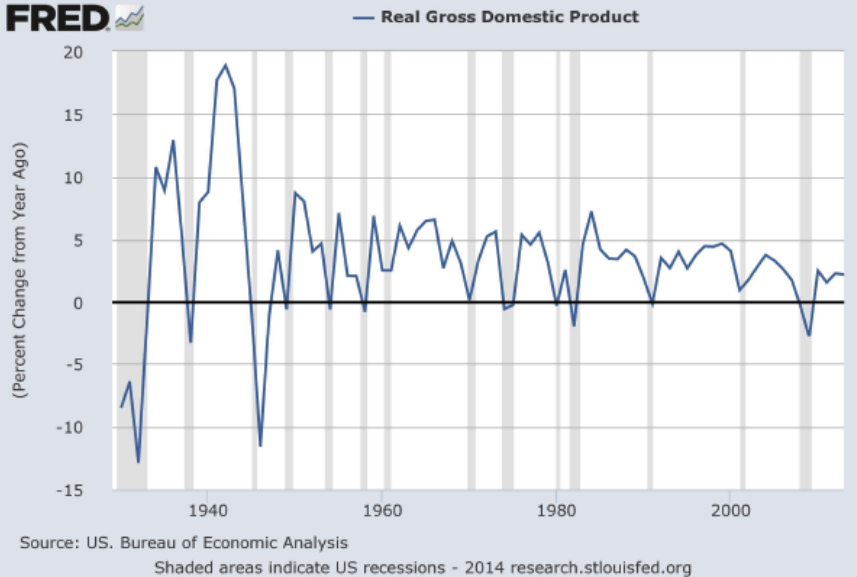

This is the inevitable dance of interest rates and inflation. Almost always, the interest rate is positive, which rewards saving, while almost all the time the inflation rate is positive, which encourages spending. The famous New York economist from a century ago, Irving Fisher, observed that the net reward to saving, the real interest rate, is the nominal interest rate less the inflation rate.

This real interest rate is typically around 3% in the U.S. and Canadian economies. Lately, the real interest rate is negative. This unhealthy discouragement to saving was designed to ensure any cash was reinjected into the economy to act as a monetary stimulus.

How about the exchange rate, though? One of the reasons why the ECB needed to raise its interest rate was to fight inflation, as we do in the U.S. as well. But, the other reason was to increase the value of the Euro. Its value had fallen to an almost historically low value of par with the dollar, which is fine for me as I follow the Tour de France, but not so good for European citizens who find that foreign goods are suddenly too expensive.

Since economies inevitably import goods, a weakened exchange rate raises prices for imported goods and hence exacerbates inflation. By raising the ECB discount rate, the reward to saving in Europe increases relative to elsewhere. More investors are willing to transfer funds to Europe, which drives up the demand for Euros and, like any other demanded commodity, increases the Euro.

Central banks must take into account this international dimension in their fight with inflation. This week provided a stark example of the internationalization of monetary policy in action.